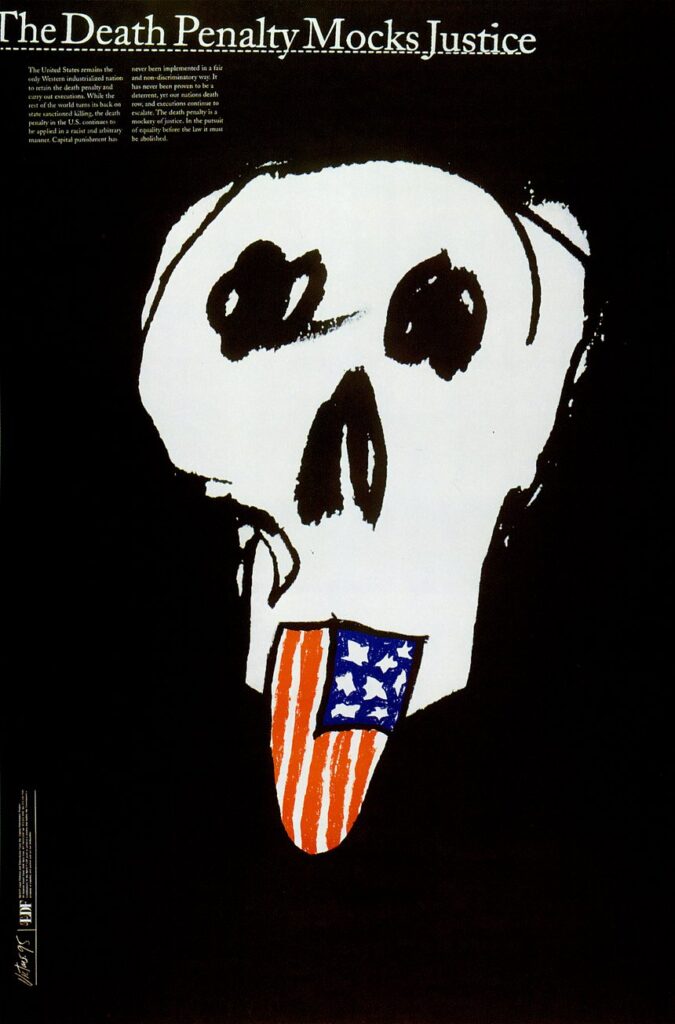

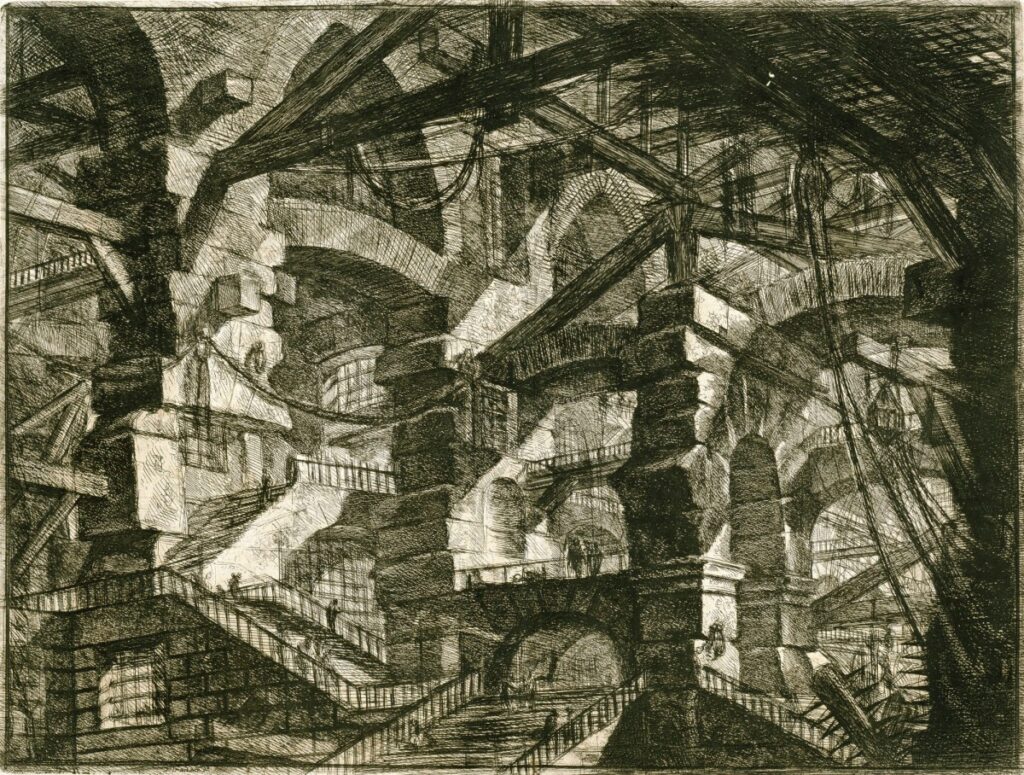

This ceramic piece, ‘Cell’, is a recreation of the adult prison cell Eve McDougall was detained in as a 15-year-old, after breaking a window.

Despite programs that ostensibly were designed to reduce prison populations, The Guardian today reports, “The prison population could top 100,000 within five years in England and Wales …. The justice department acknowledged that a perfect storm of rising prosecutions, politicians bringing in higher maximum sentences, and soaring numbers of people on remand – meaning they are in jail awaiting trial or sentencing – are responsible for the projected rise.” While The Guardian doesn’t specify this, the “soaring numbers of people” on remand are women. Where are the women? Innocent until proven guilty and behind bars.

According to this week’s Ministry of Justice report, “The number of people remanded in custody increased from 16,196 at the end of September 2023 to 17,662 at the end of September 2024. This is above the level projected in all scenarios in the 2023-2028 publication and is around 1,600 higher than projected in the central scenario which projected the remand population to fall over this period. The growth in the remand population over 2024 has been primarily driven by higher-than-expected demand entering the system, and slower than previously projected growth in the number of prisoners flowing out of the remand population following a trial. This population is projected to increase in all scenarios, with demand entering the court exceeding disposals over the projection horizon. At the end of September 2025, the projected remand population is 4,500 higher than the 2023-2028 projected remand population.”

So, who are the people making up this unanticipated growth? According to an earlier report, published in May 2024 (by the outgoing Sunak government), “There has been a 25% increase in the remand women’s population from December 2022 to December 2023. As of December 2023, women on remand accounted for 22% of the women’s prison population.” What do those numbers mean? Last week, James Timpson, the current United Kingdom Minister of State for Prisons, Parole and Probation, appeared before Parliament to answer just that. When asked what percentage of women were remanded into custody in each of the past two years subsequently (1) were not sentenced, (2) received a community sentence, and (3) received a sentence of less than six months, he produced the following chart:

Proportion of outcomes for women remanded in custody at criminal courts, 2022 to 2023, England and Wales

| Outcome | 2022 | 2023 |

| Not sentence | 14% | 16% |

| Community sentence | 13% | 13% |

| Custodial sentence of less than six months | 18% | 20% |

Again, what do these numbers really tell us? According to the Howard League, “The proportion of women on remand is both higher than in the men’s estate and growing at a faster rate, and vulnerable women are still remanded to custody as a ‘place of safety’, while the government is struggling to keep women in prison safe …. Over half of the receptions into prison are of women on remand and a third are of women serving short sentences.” Finally, according to a recent report from the National Police Chiefs’ Council, “Proportionately, more women than men are remanded in custody, and women remanded in custody at Crown Court are much less likely to go on to receive a custodial sentence than men (52% vs 71%).” For example, according to the Police Chiefs’ Council, in 2022, 85% of sentenced women received a fine and 5% a community sentence. In fact, of women convicted of anything, less than 1% were sentenced to more than 6 months.

None of this is new or surprising: not the rapid rise in prison population, nor the surge in women held awaiting trial, nor the relative diminishment of that gendered significance. Under Conservative, under Labour, it doesn’t matter. The reports come out, the performative surprise, even shock, is declared, the world moves on, except, of course, for the women, stuck in prison for absolutely no reason other than structural misogyny. Where are the women? Exactly where they have been, wasting away in cages of our collective making.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: Eve McDougall / The Guardian)