South Africa’s Covid-19 economic stimulus plan contains several of the features of a solid emergency plan, albeit cobbled together under the most unusual circumstances, at least on the surface. At 10% of GDP, far higher than Italy, Spain or the United Kingdom, it is one the largest stimulus packages in the world. To put this into further perspective the United States has committed 11% of its GDP to keeping the lights of its economy on.

President Ramaphosa’s announcement arrives at a time that global economic markets are haemorrhaging, a sad necessity of withdrawing large percentages of the working population from public spaces. Like so many components of the Covid-19 pandemic, we are presented with ongoing trade-offs and dilemmas all of which lead to their own paths of landmines. The largest fork in the road globally has been the cost of closing down the economy whilst livelihoods are increasingly precarious, many communities are restless, some families are starving to death. For countries in the Global South such as South Africa with lower welfare, this is all the more complicated by the uneven pace of dispensing relief to small businesses who employ the largest chunk of the employed workforce. The effort has been further hampered by the disgraceful diversion of food parcels to economically vulnerable communities by parts of the very state machinery that should be distributing relief.

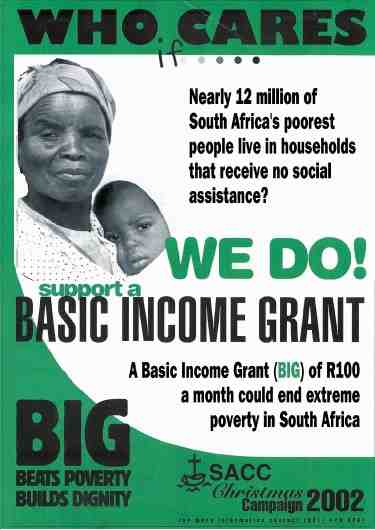

That said, the plan offers clusters of intervention, many of which sound encouragingly social welfarist. It is not dissimilar to the basic income grant suggested by social policy analysts and formulated by several NGOS post 1994. As long ago as 2004, a coalition of NGOs, faith-based organisations and unions across SADC formulated well-researched funding models to finance this. They suggested that the Basic Income Grant (BIG) was affordable, particularly for South Africa, and noted that the political and economic history of South Africa would otherwise consistently reproduce the toxicity of racist and race based social and economic outcomes. These have produced the intergenerational, structural flaws in South Africa’s economy which no amount of foreign direct investment and market orthodox approaches of the past 22 years have resolved.

The proposals suggested a financing menu of diverse local taxes and strongly suggested that a universal grant would be part of a developmental social compact. So while painful, the Corona virus and the measures suggested by the President might be bringing us closer to the recognition that structural deficits need to be addressed by investing into developing key sectors of the economy, enabling workers to remain in the economy and by cushioning those who are not able to participate in that economy.

Part of this compact is the R200 billion loan scheme to provide companies with relief to remain operational and to pay salaries. At a time when almost a third of the workforce have either been retrenched or are uncertain of their post lockdown future, a R50billion grant has been introduced to augment existing grants for a six-month period. Significantly, relief will be offered to people who are out of the current benefits matrix and receive neither Unemployment Insurance Fund benefits nor social grants.

The R100 billion grant to small businesses includes spazas and those often bypassed and ‘informalised’ by conventional market policy. These horizon industries, including chisa nyamas, are largely bootstrap businesses that play a significant role in job creation, community welfare and even a space to report domestic violence. They act as a meeting place for many, and the intimacy of the relationships represents an important part of community welfare in ways that larger supermarkets cannot replicate. During this virus, with limited transport, these outlets are the closest retailers. R70 billion in the proposal represents a tax respite for such businesses, including on skills development levies.

The second major fork in the plan is in the distribution of all this to various stakeholders. To be fully effective, cash transfers and relief subsidies must reach their intended targets including indigent communities, people in the parallel or ‘informal’ sector, and women who largely run household economics and are placed at the helm of social reproduction. They must also represent value for money. The modalities of transfer funds are risk-filled not least because the State itself has often been unreliable and corrupt. The perceptions around cash transfer programmes are often tainted with misinformation, poverty shaming and the idea that social grants or income support are for ‘free loading’ or ‘lazy’ social delinquents and ‘welfare queens’ rather than a recognition that these grants can enhance human capital and social engagement. It is also a form of risk sharing which potentially minimises the ongoing risk of huge parts of the population falling out of the social and economic compact, absent from the market economy. There is little evidence to support the view that child maintenance grants result in dependency. This is the moment to reframe a socio-economic inclusiveness that is not biased towards corporates. If 2008 taught us nothing else, it’s that we cannot privilege companies over workers and families.

The strained and compromised SASSA machinery would require far greater capacity to minimise risk and maximise fast delivery. Conditional cash transfers linked to particular goods like school uniform, services like medical access or specific food items at listed outlets have often worked better than unconditional transfers in other developing economies to avert the flaws in the systems. The sustainability of these transfers and subsidies was debated as soon as the President mentioned the 6-month time horizon. Most economies, sectors, companies and families will still be on the difficult road to recovery beyond November 2020 and probably into the next 24 to 60 months.

All this comes at a cost and herein is the final fork in the road, the IMF. The IMF presents a departure from South Africa’s correct historical aversion to securing their assistance. The IMF works on capital account liberalisation, removing barriers to flows of capital; and fiscal consolidation, or austerity. Structural conditions, or Structural Benchmarks (SBs), involve economic actions that require legislation and critical policy changes.

In 2008, in 21 countries over two decades, researchers demonstrated that IMF programme conditionalities help produce worsening health outcomes. Whilst this Corona inspired compact is an opportunity to rethink our economic model, it is crucial to appreciate that this moment is partly a manifestation of historical neglect and a market orthodox model. The solution in form of IMF and World Bank funding models may in fact lead to even more indebtedness and invidious conditionalities in future. A full cycle of market led, corporatist potential disaster. The real pandemic.

(Image Credit: Medialternatives)