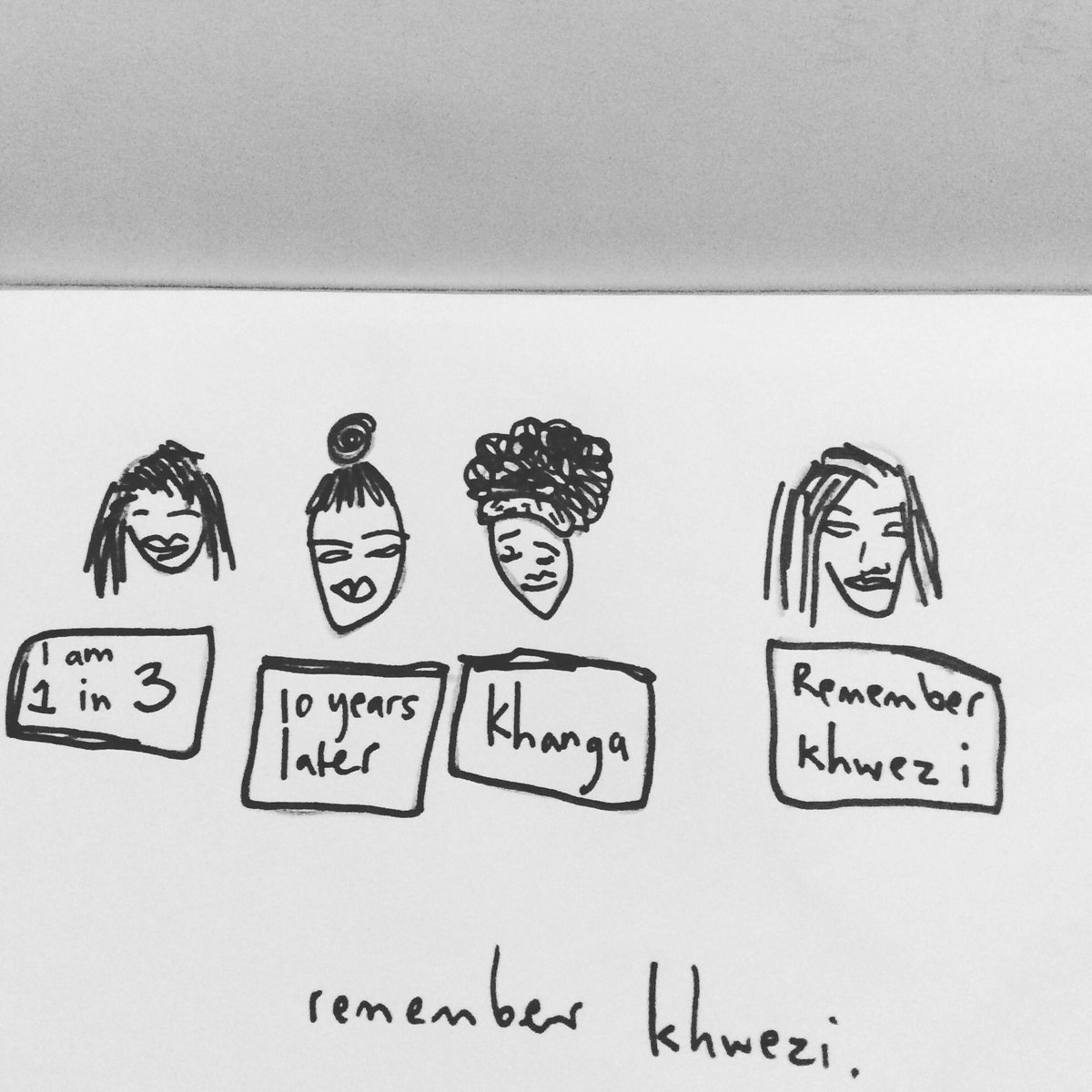

“I’m one in 3,” one placard read, referring to a claim that one in three women in South Africa will be raped in her lifetime. “10 years later”, “Khanga” and “Remember Khwezi”. Rape trials don’t ever go away for those who are the complainants. They don’t go away for those who are the family and loved ones of the survivor, and for many in the criminal justice system, they also suffer vicarious trauma. Trials are hard. They take their toll. The silver bullet solution in rape cases is re establishing the so-called Sexual Offences Courts. Sexual Offences Courts are designed to deliver survivor-centred justice with specialised services, specialised infrastructure and specialised personnel.

The idea is simple enough. Take every single link in the criminal justice system affecting rape survivors and make sure it holds the survivor in the system. From the very first report, through meeting the detective, to the first interview with the prosecutor. Make sure everyone is trained in all the special laws and processes you need to implement to get the rape kit, and survivor, the accused and the other evidence and witnesses in court. Make sure the magistrate and prosecutor know not just about the rules, but how trauma affects witnesses. Children testify through CCTV cameras and an intermediary, and don’t have to look at the accused, or deal with inappropriate questions from the defence attorney. Keep the survivor functioning and in their job, taking care of their kids, making sure counseling is available when and where they need it. Prevention of STIs, and pregnancy.

The Ministerial Advisory Task Team on the Adjudication of Sexual Offence Matters (MATTSO) released the Report on the Re-establishment of the Sexual Offences Courts by the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development’s Ministerial Advisory Task Team on the Adjudication of Sexual Offences Matters (MATTSO) in 2013,which recommended the re-establishment of Sexual Offences Courts.

This report led to important amendments to the Act, being the insertion of a section which authorises the Minister to designate certain courts to exclusively hear sexual offences matters. This set of amendments has yet to be brought into operation. A set of regulations has been drafted in accordance with the amendment of the Act. These regulations have been distributed for input in 2015, but no final version has been promulgated yet. 43 Sexual Offences Courts have been established ahead of the legislation coming into operation, according to the Department of Justice.

Many people have no idea Sexual Offences Courts exist, and certainly no idea how the rules are different in that court. So they don’t monitor how the courts are functioning. They do need to monitor them, as in any complex system requires monitoring by people who know what’s going on. But this is a process that involves survivors of violence who are often reluctant participants in the process. They don’t want to be reminded of the events that have led them there, and they don’t want to relive them. They don’t want to answer questions about where they were, and why, and how sober they were, and whether they were ‘friendly’ with the accused. Monitoring whether the court is being run properly is well beyond what can be asked of them.

It’s also, startlingly enough, beyond organisations that are specialists in the area, and that’s because we don’t actually know what the absolute requirements are for such a Court. The principles are clear – specialised services, specialised infrastructure and specialised personnel. However, getting all three working together requires inter sectoral co operation between the Department of Justice, the National Prosecution Authority, and the magistrates.

Without the framing law in place, its harder than herding cats. We have Tutuzela Care Centres, which are a one-stop shop for reporting sexual offences. Doctors, police, and counselors are all there as first responders. We have courts that have the right infrastructure, and we have courts that have specially trained prosecutors. There are also magistrates who work in specialized courts, although they tend not to have a list of cases, which are only sexual offences. What we don’t have is a clear picture of where this is all happening at the same time. So it’s possible to have a court with a specialised prosecutor, but not the right infrastructure. Or a Tutuzela Care Centre with no sexual offences court.

It may be for those who monitor the courts to come up with some rule of thumb, which allows civil society to declare which courts are in fact sexual offences courts. Like free and fair elections, the ones who are outside the system are well placed to observe the successes and failings of the system. Civil society will be launching a campaign this week to hold the state to account on their promises. But ultimately, a high degree of awareness of the rules, and a high degree of compliance is always part of a system working well, and we need to establish those rules before we can say the sexual offences courts are the criminal equivalent of free and fair.

Maybe it wouldn’t have made a difference for Khwezi. But it might well have. There is enough evidence of better conviction rates in those courts, and lower secondary and vicarious trauma to make it worth continuing to work, link by link, to make that chain of conviction work. #rememberkhwezi

(A slightly different version of this article first appeared at The Daily Maverick. Thanks to Alison Tilley for sharing this here.)

(Photo Credit: Greg Nicolson / The Daily Maverick) (Image Credit: Twitter / Lady $kollie)