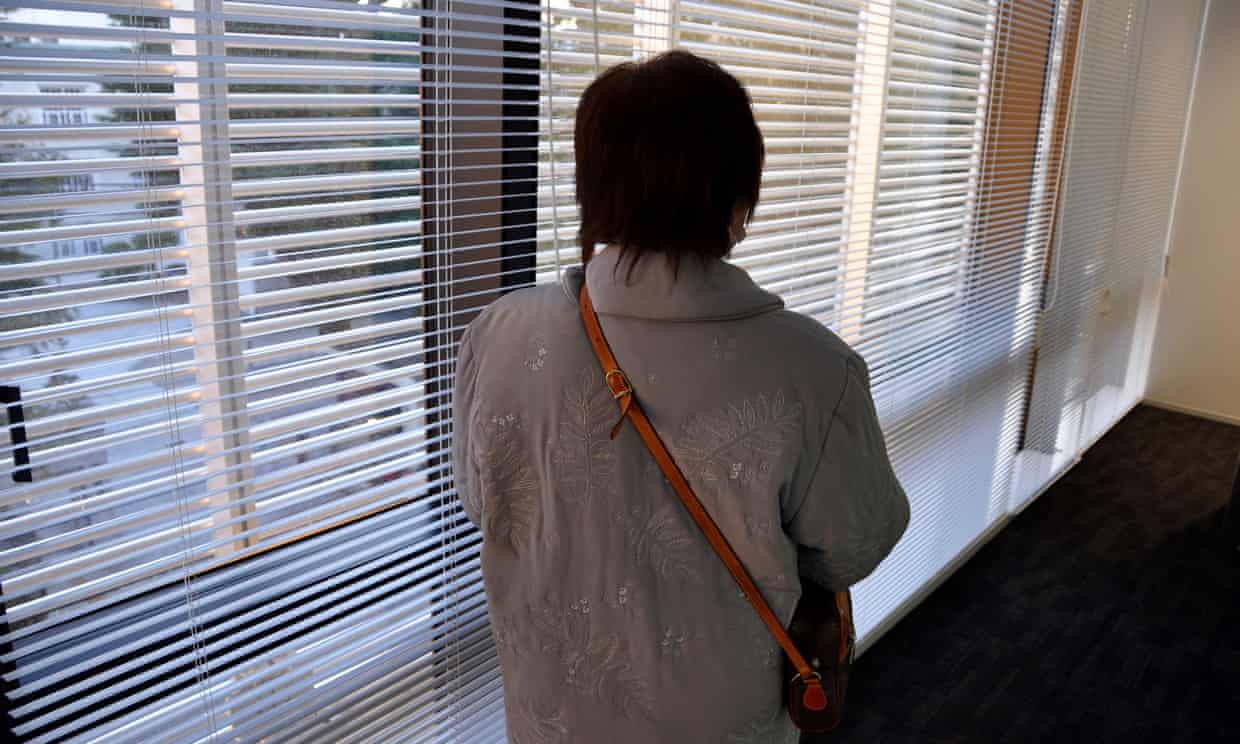

When she was 16 years old, Junko Iizuka was forcibly sterilized.

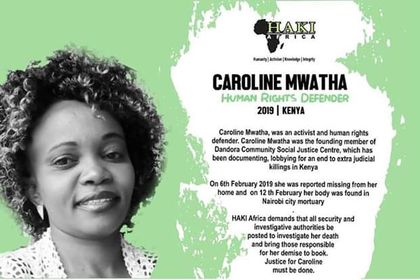

On Thursday, March 14, all major parties in Japan agreed to pass a measure, probably in April, that would “deeply apologize” and offer compensation to victim-survivors of forced sterilization. The compensation would be a one-off payment of around $28,700. Now we know the value of life in Japan … and elsewhere. Survivors and their supporters and advocates argue that the compensation is way too little and way too late. Japan suspended its 48-year program of sterilizing those who might produce children described as “inferior”, under a law called the Eugenics Protection Law. The youngest known victim was 9 or 10 years old; 70% of those sterilized were women and girls. Since 1996, women and supporters have organized and demanded recognition, compensation, apology, dignity and justice. It only took 23 years to arrive at something approximating any of their demands, and that was largely due to a barrage of civil suits initiated last year. Forced sterilization is a formative element in contemporary nation-building, and Japan is not an outlier in this matter.

From 1935 to 1976, Sweden sterilized womenit deemed socially or racially inferior. `No one’ know about this program until it was revealed in 1997. In 1999, Sweden agreed to pay victim-survivors a one-off payment of $22,6000. Then, in 2012, it was `revealed’ that Sweden required transgender people to undergo sterilization. The law requiring sterilization was passed in 1972, but “no one” knew. In February 2012, thirty years after its passage, the law was repealed.

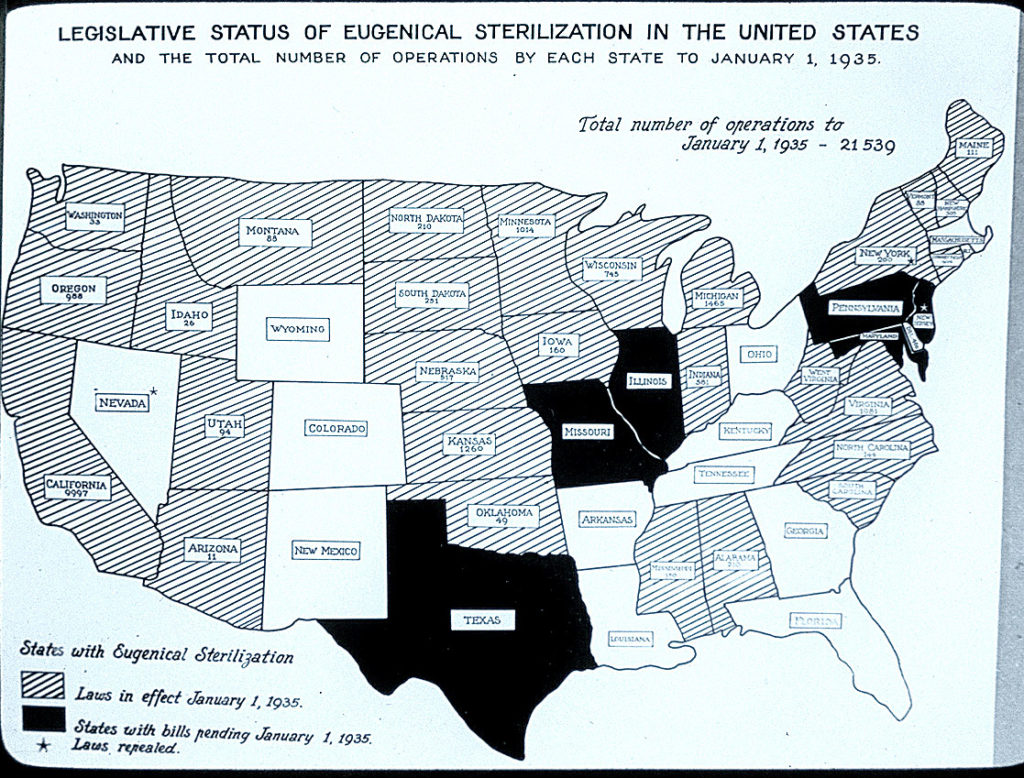

Japan now joins the list of nation-States dealing, and not dealing, with their histories of forced sterilization: Peru, South Africa, Namibia, India, to name a few that have addressed the issue in the last few years. Sometimes the ostensible reason is health care, particularly HIV; or population control; and the list goes on. No matter the immediate explanation, the reason is always “protection.” In the past few years, in the United States, California, Virginia, North Carolinahave addressed their histories of forced sterilization. The United States has not addressed its history of forced sterilization of Native women. Nor has Canada.

Every program of forced sterilization had a justification. Every later discovery offered an alibi, most of which argued `the times were different’. That was then. The problem is that now is then, as then was now. Forced sterilization of women and girls is baked into the formation of citizenship in the modern nation-State, every single one without exception. It is the signature of nation-State modernity. As long as the State produces and reproduces hierarchies of citizenship, that’s how long the nation-State will find ways to accommodate forced sterilization of women and girls. For `our’ protection and security. There is no apology deep enough to address that constitutive and absolutely ordinary atrocity.

(Photo Credit: Daniel Hurst /The Guardian) (Image Credit: PBS / Truman State University)