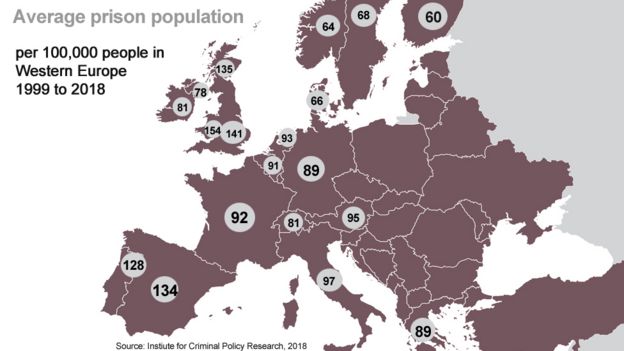

Wales, England and Scotland lead Western Europe in rates of incarceration

Today, the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University released a report, Sentencing and Immediate Custody in Wales: A Factfile. It’s the first report to disaggregate Wales incarceration figures from those of England. Wales has the highest incarceration rate in Western Europe, with England a close second. Wales comes in at 148 per 100,000; England at 141 per 100,000; Scotland at 135 per 100,000 and bursting at the seams. Northern Ireland lags with a mere 78 per 100,000. (The United States clocks in at 698 per 100,000). The numbers in Wales reflect a State criminal justice system that is deeply racist and misogynist. The report concludes, “While the discovery that Wales has the highest imprisonment rate in Western Europe is a cause of major concern, equally disturbing is that such an alarming trend has emerged in Wales without detection.” The alarming trend is “that non-White Welsh prisoners are overrepresented in prison and that the likelihood of receiving a short-term sentence is greater for those sentenced in Wales than in England.” Who receives the short-term sentences? Women.

Women: “Women are more likely to be given shorter custodial sentences than men. More than three quarters (78.6%) of all females sentenced to immediate custody in Wales between 2010 and 2017 were handed sentences of less than 12 months. This compared to 67% of male offenders sentenced in Wales during this period. The frequent use of short-term sentences often brings considerable `chaos and disruption’ to the lives of women and their families. Recent research has also shown that women sentenced to short-term custodial sentences are more likely to re-offend than those sentenced to a court order … One in four women (24.8%) sentenced to immediate custody in Wales were sentenced to a period of one month or less in prison between 2010 and 2017. This compared to a rate of 15.2% for men in Wales.”

At one level, none of this is new. England and Wales, taken together, have had the highest prison population rate in Western Europe since 1999. Year after year after year, the incidence of women’s suicide and women’s self-harm while in custody has broken previous records. What is new is that Wales is worse, and that the cornerstone of being Incarcerator Number One is race and gender. The report does not provide intersectional data, for example the treatment of Black women in Wales, but one can only imagine that if it’s bad of Black people and it’s bad for women…

Why does Wales insist on incarcerating so many women? Protection. The State is [a] protecting women from themselves and [b] protecting women as vulnerable beings. Women are being arrested more often for minor offenses, and then are being imprisoned for short periods of time, all this despite volumes of research that document that short-term “custodial sentences” do not work. Put differently, they succeed in further and more deeply enmeshing women into prison networks. What is the mechanism that combines pipeline and revolving door? Ask the women of Wales. For women, living in Wales, “one of the poorest parts of the UK”, has become both a survival to prison pipeline and a never-ending and ever faster spinning revolving door. Tell the Welch government, tell the “justice agencies in Wales as well as civil society organisations and academic researchers” that living as a woman is not a crime.

(Infographic: BBC)