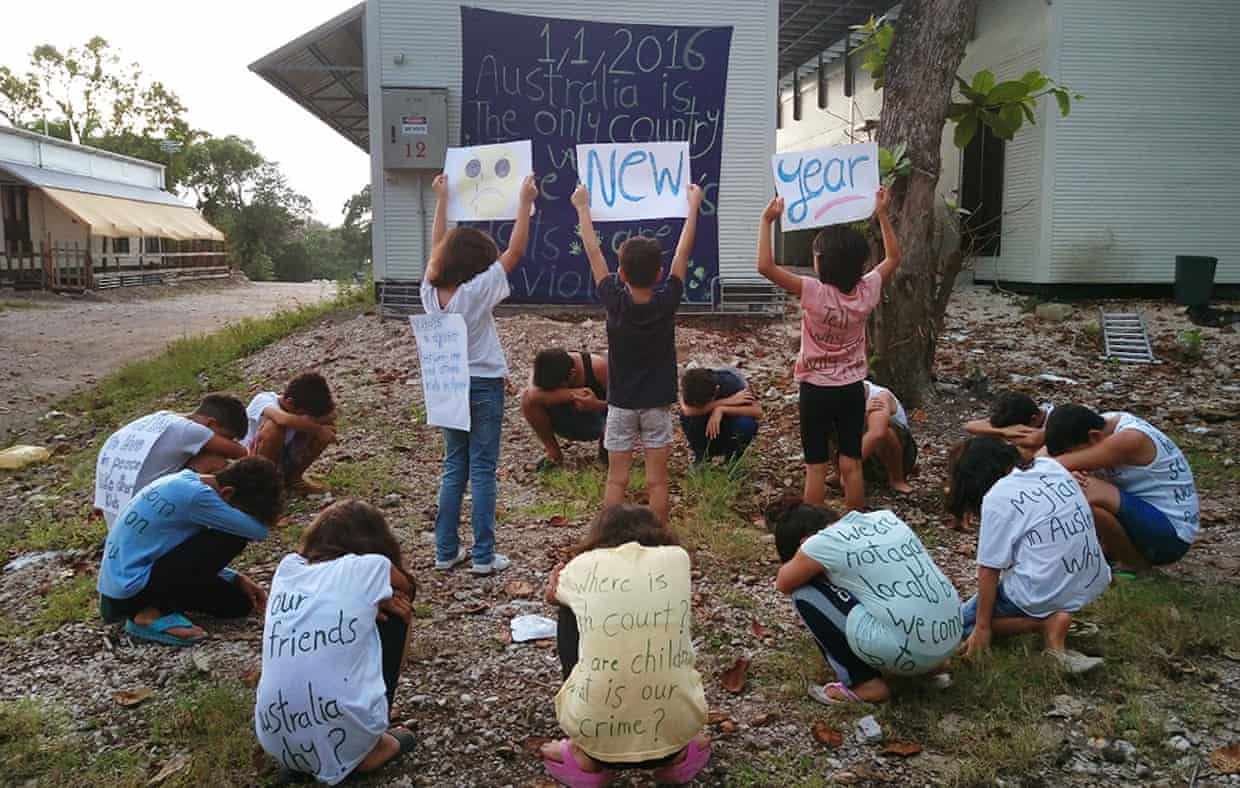

Yesterday, August 9, across South Africa, people acknowledged, in various ways, National Women’s Day, the annual commemoration of the 1956 Women’s March on the Union Buildings, in Pretoria, to protest the pass laws and much, much more. On August 1, across South Africa, thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of women and gender non-conforming people engaged in an “intersectional women’s march against gender based violence” and stayed away from all work and commerce. This was under the banner, #TotalShutdown. Organizers asked people to find ways of supporting those women who were forced to work that day. Additionally, for women in rural areas, where a march to a High Court might not be feasible, women were asked to `simply’ stand together, to unite and stay away from work and commerce. In between August 1 and August 9, on Sunday, August 5, Barbara Hogan, anti-apartheid activist and politician, returned to the Women’s Jail, now turned into a museum, on Constitution Hill in Johannesburg. Hogan remembered her stay in that prison from 1982 to 1983. On Women’s Day, in Women’s Month, and in the #TotalShutdown, where are the women prisoners? Where are South Africa’s women prisoners, generally, and where are they in the movements for women’s emancipation and power?

According to the most recent Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services Report, covering April 2015 to end of March 2016, South Africa has 236 operational prisons, of which 9 house women prisoners. Only 2.6 percent of prisoners are women. As Johann van der Westhuizen, the inspecting judge of Correctional Services, noted, this is “one of the lowest percentages in the world. Not bad for a population that is just more than half female. This means slightly more than 4 000 women are in jail — some with their babies.” Not bad? No. Johann van der Westhuizen continues, “Women’s prisons are also overcrowded. I was told that a cell for 25 with 37 inmates was not overcrowded. And that, in other instances, additional mattresses were put on the floor, almost doubling the number of inmates.”

The number of women in prison is low, and yet the women’s prisons are notoriously overcrowded. How can that be? Part of the answer appears in van der Westhuizen’s report, “Due to the high turnover rate of remand detainees, remand units were found to have deplorable health conditions and dilapidated infrastructure compared to those occupied by sentenced offenders.” Pollsmoor Remand was 251% overcrowded, and was “short” 2448 beds. According to the Department of Correctional Servicesmost recent annual report, 2012 to 2017, the number of male remand prisoners has declined fairly steadily, from 44,742 to 41, 397, while women’s numbers have risen, from 998 to 1,128.

What does that look like “on the ground”? For women prisoners, and especially for those awaiting trial, from overcrowding to access to healthcare to food to hygiene and sanitation to access to education, reading materials, decent work or any work, exercise and recreation, to contact with the outside world, the conditions are “horrifying.” At Pollsmoor, for example, more than half of the women prisoners are awaiting trial. Many wait years for a trial that is often thrown out or postponed indefinitely.

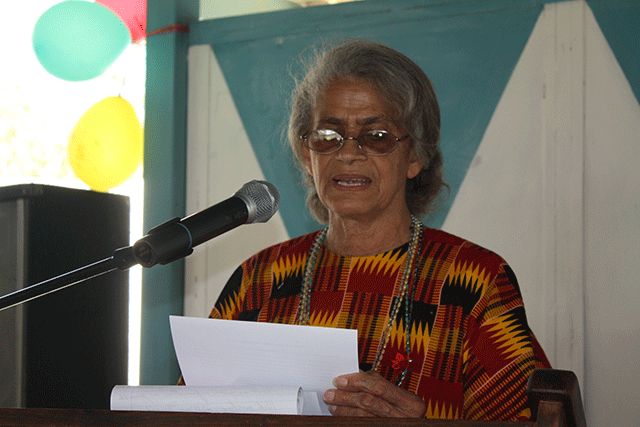

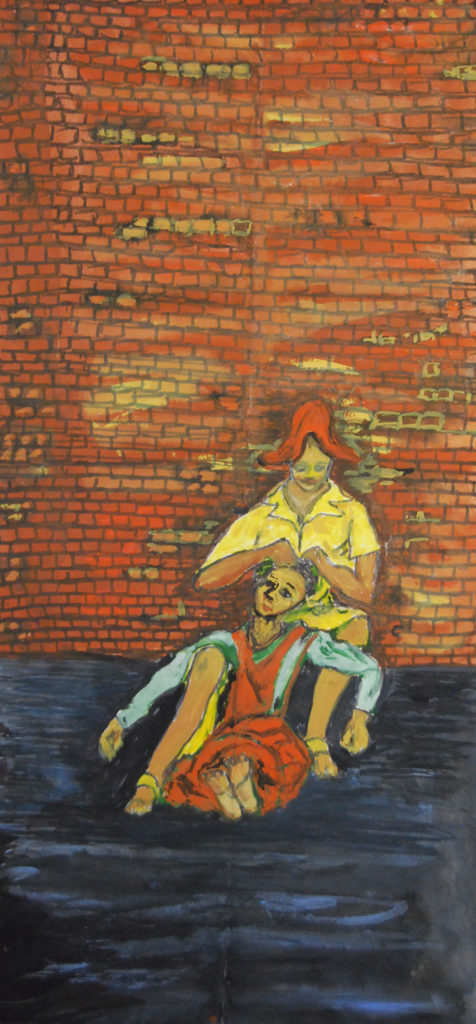

Reflecting on her experiences in prison, Barbara Hogan commented, “Prisoners do not need to be told that policeman beat up prisoners. They know it.” Last year, in August, the Women’s Jail opened a new exhibition, paintings from that jail by anti-apartheid activist Fatima Meer. The paintings’ very existence testifies to the myriad forms of women’s persistent, resistant and defiant organizing. At the same time, they speak to the ongoing squalor and dehumanization of women behind bars. The conditions of women prisoners, in particular women remand prisoners, is not an oversight. Those women have not been forgotten. They have been dumped, disposed of, and that’s public policy, not some accident. Prisoners do not need to be told that, but the public does. Someday, along with the Union Buildings and High Courts, women and their supporters will march to women’s prisons across the country to acknowledge, learn from, and build on the intersectional women’s organizing taking place each and every day among those women who are forced to sleep standing but never surrender.

(Paintings by Fatima Meer; Kajal Magazine)