A specter is haunting the global economy: the specter of workers organizing. All the powers of the old and new global economy have entered into an unholy alliance to exorcise this specter, but it just keeps coming back. Actually, it never left. In South Africa this week, organized and organizing workers received encouraging decisions from two separate tribunals. In one case, workers hired through labor brokers, also known as temporary employment services, were told that if they are employed by someone for three months, that makes them employees of the contracting company. In the second case, Uber drivers were adjudicated as employees of Uber, rather than as `self-employed contractors.’ Both decisions will be appealed, but the decisions clarify the status of laborers as they affirm that workers know who they are and they know who their bosses are. Additionally, the decisions have clarified the lines of antagonism. Aspects of class struggle may change, but the essence, exploitation of workers’ labor time, has not.

The case concerning “temporary” workers involved the National Union of Metalworkers, Assign Services and Krost Shelving and Racking. Assign Services provided Krost with workers. Many of them worked for more than three months. The decision by the Labour Appeal Court in Johannesburg means that workers can’t be summarily fired, they have the right to appeal mistreatment, they have collective bargaining rights, and that they qualify for benefits, including retirement and health benefits. In other words, they are permanent workers, no matter what the terms of client to labor broker contract claimed.

This is a victory for workers considered by many to be among the most vulnerable. It also regulates temporary employment services to actual temporary employment status. Once the three months have been hit, the temporary employment services are no longer needed. This also means that workers who have fallen into this double bind, and they are many, can now begin organizing, and litigating, in response to previous damages.

That decision was handed down on Monday, July 10. On Wednesday, July 12, the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration, CCMA, ruled that Uber drivers are employees of Uber, and so are protected by South African labor laws. In this instance, former Uber drivers, who had organized into something called The Movement filed a complaint concerning unfair employment practices. In particular, they protested having been summarily dismissed by Uber, without cause, reason or possible appeal. They explained that being fired by Uber happens when Uber simply turns off their app. No warning, no process, no nothing. Just silence. Their appeal gained further weight when Uber claimed the CCMA couldn’t hear the case because the drivers are “partners”, not employees. The CCMA didn’t buy that, and so now, Uber drivers have the right to all protections afforded employees: collective bargaining, due process, strike.

Neither case is definitive, and further appeals are already in process, but the cases, individually and taken together, matter. Workers know who the boss is, and they also know the terms of workplace and workforce engagement. Both cases happened at all because of workers’ organizing and organizations raising a ruckus, finding good attorneys, and then raising more of a ruckus. Workers know the difference between temporary and permanent, and they know that permanence, such as it is, is only secured through collective action. The workers also know the entity that fires workers is the employer. Who’s the boss? Ask the workers.

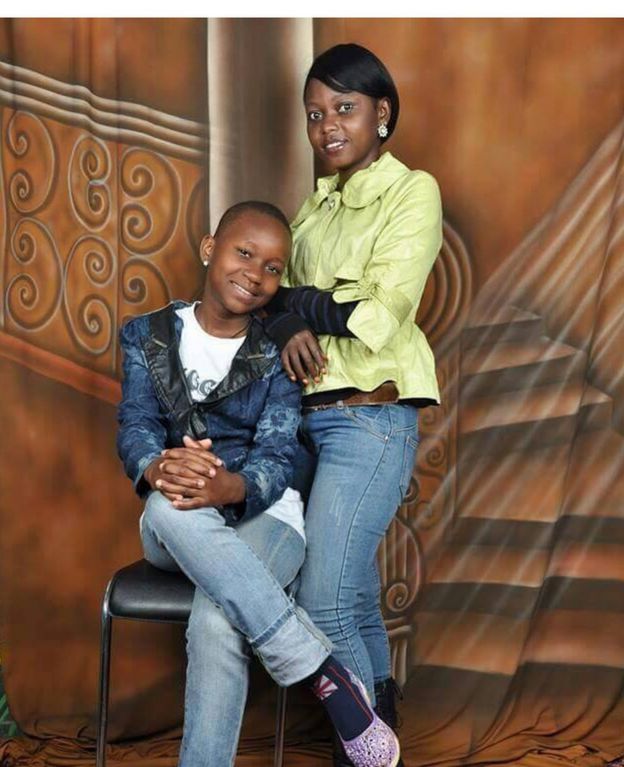

(Photo Credit 1: Business Day / The Times) (Photo Credit 2: Quartz / Reuters / Siphiwe Sibeko)