In the past week, news agencies and advocacy organizations have discussed the role of prisons and jails in spreading the novel coronavirus. Some are longstanding advocates for just solutions to the incarceration crisis; others, especially news agencies, are just now `discovering’ that prisons, jails and immigration detention centers form an archipelago of infectious morbidity and mortality. Headlines from the past three days include: To Arrest the Spread of Coronavirus, Arrest Fewer People. Visits halted in federal prisons, immigration centers over virus. How Coronavirus Could Affect U.S. Jails and Prisons. Prisons And Jails Worry About Becoming Coronavirus ‘Incubators’. Our Courts and Jails Are Putting Lives at Risk. To contain coronavirus, release people in prison. In Virginia, the Legal Aid Justice Center noted, “Adults and youth held in Virginia’s prisons, jails, and detention centers are particularly vulnerable to the spread of disease and deserve to be protected with adequate sanitation and medical care or, if possible, be released.” England and Wales developed “emergency plans to avoid disruption” in their prisons. Also in England, immigrant advocates called on the government to release hundreds of immigration detention center detainees, noting, “There is a very real risk of an uncontrolled outbreak of Covid-19 in immigration detention”. In France, prisoners, supporters, staff, and advocates are concerned and see no way out of coronavirus running rampant through the prison system.

While this attention is welcome, the question that lingers, and haunts, the current carceral controversy is, “Why now?” Public health researchers have long documented prisons’ role in the spread of infectious disease. From a public health perspective, prisons so dangerous because they’re overcrowded and their systems of care provision, such as they are, have intentionally gone from bad to worse. A half century of mass incarceration married to a global programme of austerity has left us with prisons waiting to pump out HIV and AIDS, TB, Ebola, SARS, opioid addiction, and now Covid-19.

Earlier this year, a special issue of The Lancet began as follows, “About 11 million people are currently being held in custody across the globe and more than 30 million individuals pass through prisons each year, often for short but disruptive periods of time .… The health profile of the detained population is complex, often with co-occurring physical and mental health disorders, and a backdrop of social disadvantage. Detention can also expose people to new and increased health risks, yet the profiles of the population behind bars and their health needs have often been neglected.”

Last year, The Lancet editorial board noted, “The sheer scale of imprisonment in the USA and its unequal burden on people from minority and poor backgrounds raises concerns about its impact on the health and wellbeing of the national population …. Being in prison worsens several health outcomes and might even drive the spread of disease.” Elsewhere, medical researchers noted, “There is a growing epidemic of inadequate health care in U.S. prisons. Shrinking prison budgets, a prison population that is the highest in the world, and for-profit health care contracts all contribute to this epidemic.”

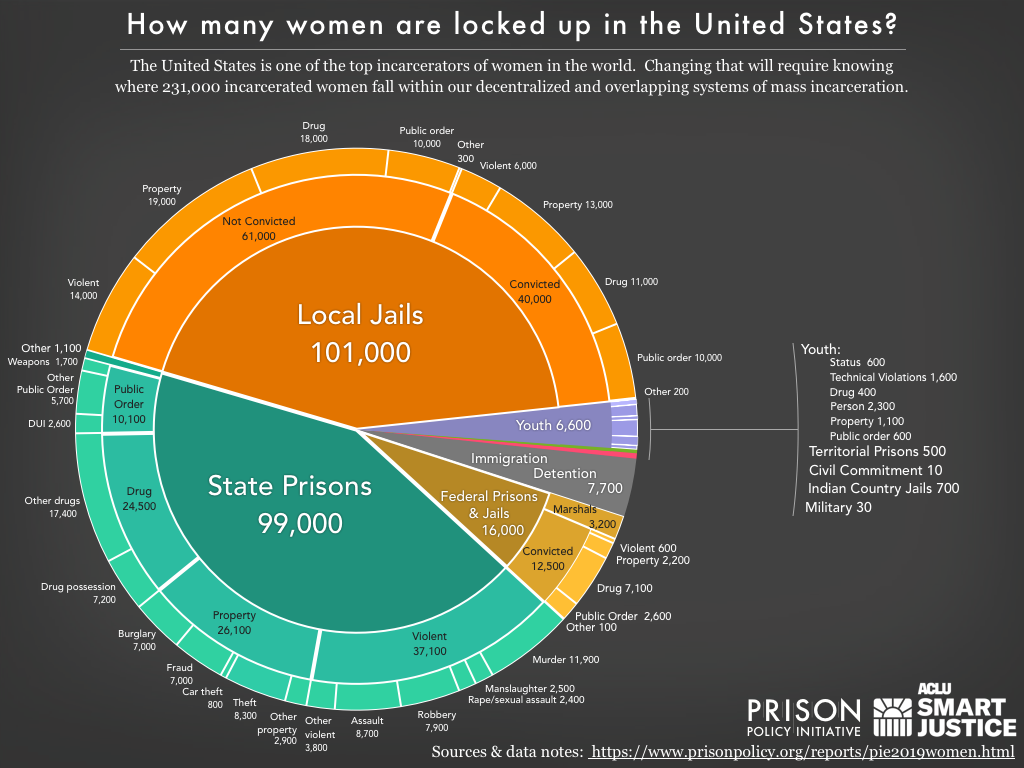

Inadequate health care in prisons across the globe is the growing pandemic that preceded the current pandemic. Where are the women in this pandemic scenario? Women are the fastest growing prison population. What does that “growth” look like? “As adults, women who are incarcerated have enduring reproductive health issues such as unintended pregnancies, adverse birth outcomes, cervical dysplasia and malignancy, and sexually transmitted infections. Women who are pregnant or parenting a newborn during their incarceration are at high risk for poor outcomes, and just like individuals in the community they need prenatal care, supports with labor, postpartum bonding, and breast-feeding support. Women who have returned to the community or are under community supervision face similar health issues as women who are incarcerated and may lack access to care.”

Repeatedly, public health researchers have described the situation in prisons and jails as a crisis. For women – and especially women of color and poor women – that crisis stretches across their lifespan in two ways. First, the health consequences of even short stays in detention endure a lifetime. Second, detention itself lasts a lifetime: “Over 1.2 million women in the United States were on probation, parole, or incarcerated in jail or prison facilities at the end of 2015, the most recent year for which data are available.”

The decades of mass incarceration, in which women have consistently been the fastest growing prison population, are built on systemic neglect. While the current pandemic is in no sense an opportunity, it is a moment in which we can turn that neglect on itself and pay attention, not only to this particular instant but to the decades that prepared the ground, toxically, for it. Immigrant detention, jail, prison are always bad for health. The only route to a healthy world is decarceration.

(Image Credit: Prison Policy Initiative)