Veronica Nelson

On January 13, Veronica Nelson, 37-year-old Yorta Yorta woman, was buried. On New Year’s Day, Veronica Nelson was charged with shoplifting and went to court that day. Veronica Nelson represented herself in court and was denied bail. She was sent to Dame Phyllis Frost Centre, a maximum-security facility, one of two women’s prisons in Victoria, Australia. At 8 am, January 2, Veronica Nelson was found dead in her cell. Her family, heartbroken, has questions. Her friends and community, grieving, have questions. Another Aboriginal woman dies in custody. Each time an Aboriginal woman has died in custody, we have asked, “What happened to her?”: Ms. Dhu, Cherdeena Wynne, Rebecca Maher, Joyce Clarke, Ms. M, Maureen Mandijarra, Tanya Day. Remember Tanya Day, 55-year-old Yorta Yorta woman who, in December 2017, died, or was left to die … or was killed, in police custody? Her coronial inquest was barely finished when Veronica Nelson died. “What happened to … ?”, we asked. It was the wrong question. We should have asked, “What happened to justice?”

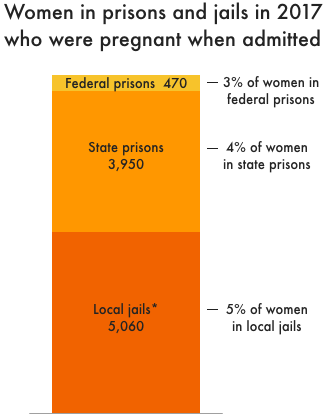

Australia has built a special hell for Aboriginal women. “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in prison are the fastest growing prison population, and 21 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-indigenous peers.” That was reported in February 2018, and it wasn’t new then. These very issues arose in major reports published in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017. It’s 2020, new year, new decade, and Veronica Nelson is dead.

Her family reports that other women prisoners at Dame Phyllis Frost Centre report that Veronica Nelson was in great pain, screaming out for help. Veronica Nelson’s sister, Belinda Atkinson, said, “She’d gone up to medical asking for help, could she get something for her drug problem. She’d gone up there and asked for help and they’ve knocked her back, and then she was sitting in the cell crying. Crying, crying, crying, because she couldn’t get no help.”

In 2017, the Victorian Ombudsman inspected Dame Phyllis Frost Centre and gave a mixed report. At the outset, the report noted, “Overall we found positive initiatives but an ageing and crowded facility, where prisoner numbers have grown 65 per cent in the last five years and remand prisoners have more than doubled over the same period … The inspection team identified a relatively high use of force and restraint at DPFC compared with other prisons in Victoria … There is little meaningful interaction between staff and women. Several women who had been held in Swan 2 described self-harming in the unit because they felt it was the only way to get staff to engage with them.”

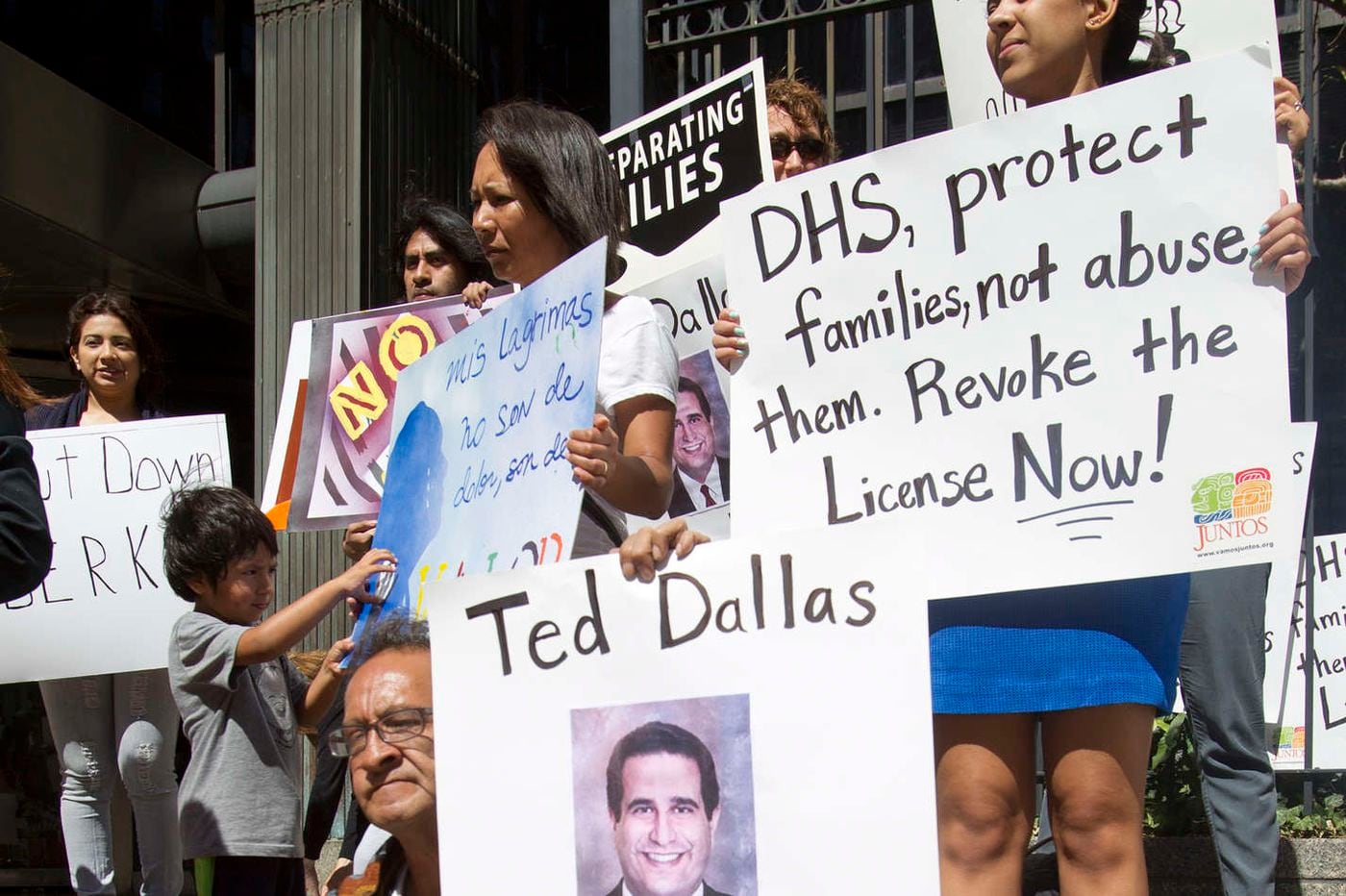

Antoinette Braybrook, CEO of Djirra, reflected, “Once again Aboriginal women’s lives are not valued. This is a death in custody of an Aboriginal woman that happened over a week ago — why are we only hearing about it now, through the media? Where is the outrage? When will Aboriginal women’s lives matter?”

The Victorian government has also responded to the death of Veronica Nelson: “As with all deaths in custody, the Coroner will investigate and formally determine the cause of death. As the matter is the subject of an ongoing coronial investigation, it would be inappropriate to comment.” The State is not heartbroken because the State has no heart.

Veronica Nelson was never meant to survive. Veronica Nelson is the most recent name of those who were never meant to survive. The family is meant to be heartbroken, drenched in and constituted by grief, and completely uninformed. As many have noted, it took eight days for the State to inform the family of Veronica Nelson’s death. What does that “time lag” suggest? There is little meaningful interaction.

What happened to Veronica Nelson? Nothing. An Aboriginal woman died in custody. What happened to Australia? Nothing. Another Aboriginal woman died in custody. What happened to justice? A contemporary postcolonial, anti-colonial politics that begins and ends with the State murder of Aboriginal women, which runs from lack of services and assistance, from cradle to grave, to mass incarceration to dumping into the mass graves of historical amnesia. What happened to Veronica Nelson? Nothing.

(Photo Credit: The Age)