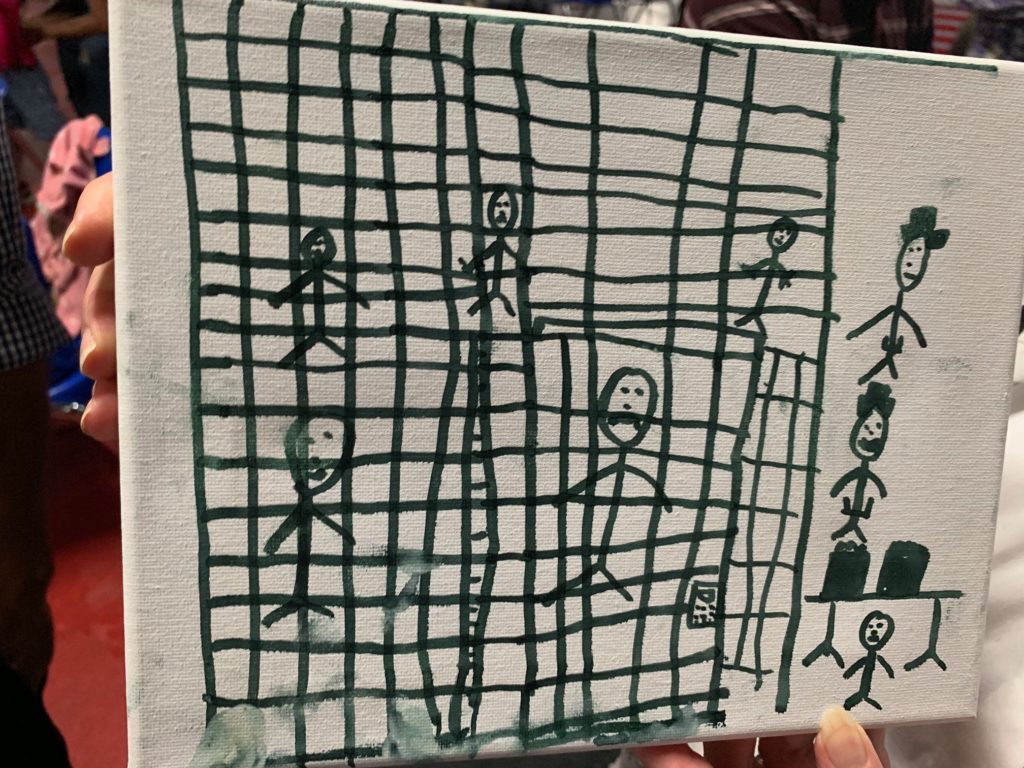

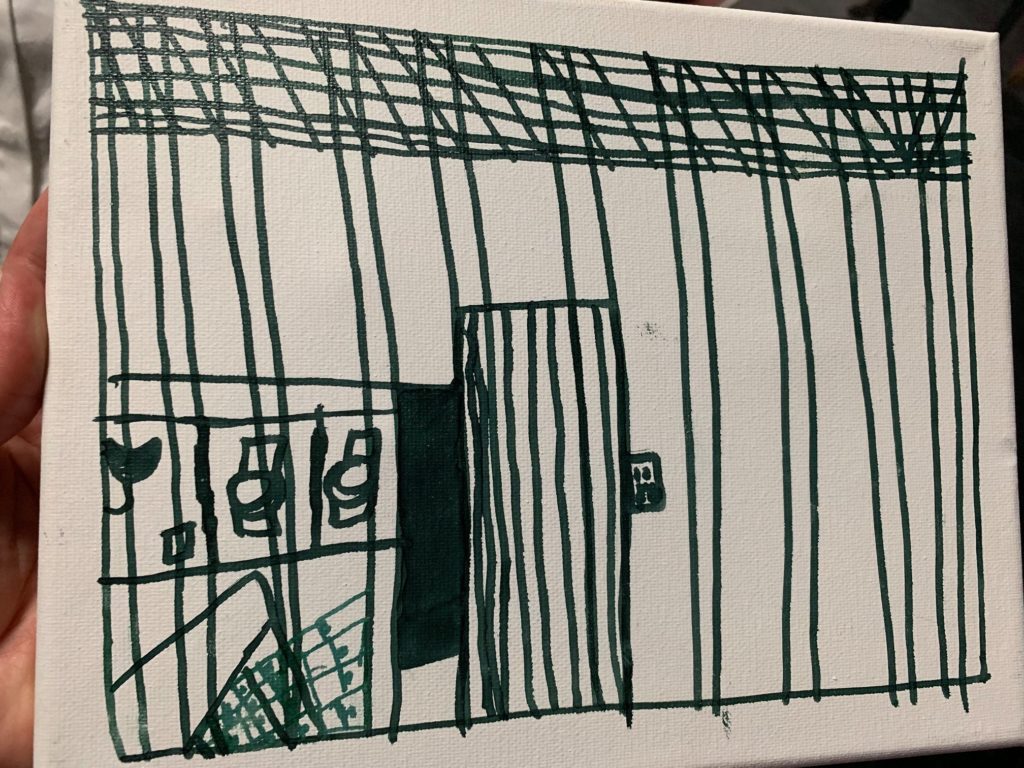

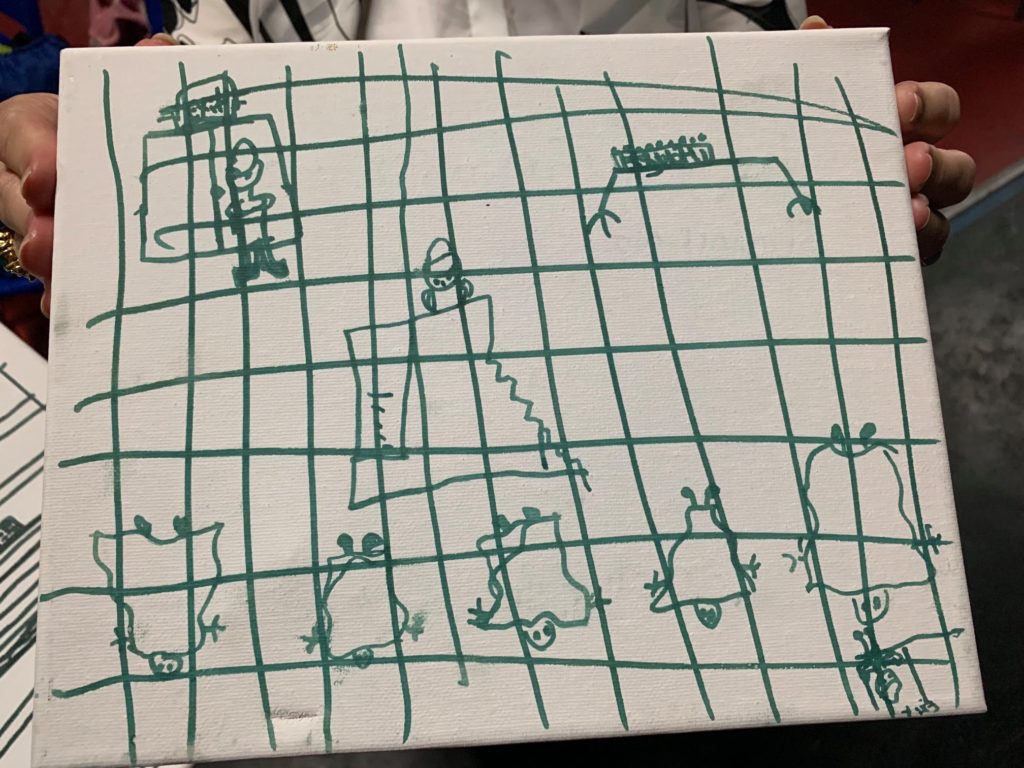

Yesterday, July 3, 2019, the American Academy of Pediatrics released the drawings below, done by children who had been held, caged, in immigrant detention centers on the U.S. Southern Border. The AAP said, simply, “The American Academy of Pediatrics believes no time in detention is healthy or safe for children.”

Today is July 4, 2019. There is nothing to celebrate here.

(Photo Credits: American Academy of Pediatrics / Facebook)