I work at a university, and it’s been a rollercoaster of emotions for students. As COVID-19 cases are rising across the country and multiple universities, professors are having to contend with the fallout, the students are suffering, both emotionally, physically, and financially. And administration, which has promised to keep students safe, to get them testing and a way back to college life, has failed.

It didn’t have to be like this.

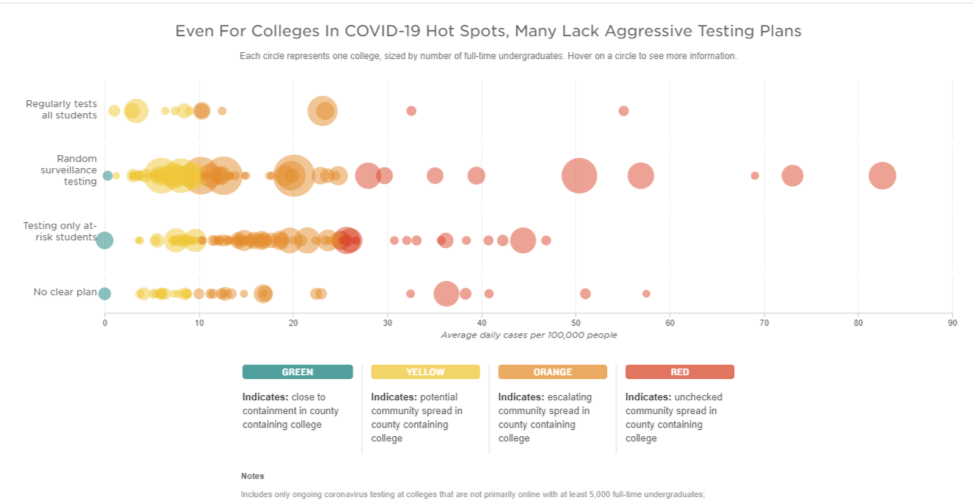

Firstly, students were promised a clear path back to the university campus—that included aggressive testing, aggressive social distancing measures, and mask mandates. The reality, however, seems to massively different than the expectation. “The first six weeks of the semester has taught colleges an important lesson: ‘It’s not simply testing—it’s testing, testing, testing,’ says Terry Hartle of the American Council on Education, a national group of college presidents, ‘but it’s an expensive undertaking.’” And the expensiveness of the tests—of more than $100 per test—is showing how difficult it is for universities to do the rapid testing that is required to keep faculty and students safe. “Of colleges with in-person classes and more than 5,000 undergraduates, only 25% are conducting mass screening or random ‘surveillance’ testing of students. Only 6% are routinely testing all of their students. Most, instead are relying on only diagnostic testing of symptomatic students, which many experts say comes too late to control outbreaks and understates the true number of cases.”

All this has contributed to universities becoming hotspots and contributing to the large increase in coronavirus cases across the country—up to a 55% nationally increase among adults by August and early September, when colleges opened for the Fall semester. In-person classes have contributed to about a 3,000 increase in cases a day in the United States.

But testing is not the only issue at hand when it comes to the university desperately trying to maintain a safe environment for workers and students. It didn’t have to be that students were made to come back to campus to do in-person classes, or hybrid classes, or even a cacophony of one class online, one class in person, one hybrid, that would make it mandatory to be on campus to begin with.

All classes should have been online.

Unfortunately, that would require universities to do something that no university, structured by a corporatist model, would have to do—cut tuition. And I don’t mean a paltry cut to tuition, that would mean administration acknowledging that the model currently makes it impossible to maintain the level of safety and health for their students than they originally thought. That means university presidents taking substantiated salary cuts and other higher administration cutting their salaries as well, so that the faculty are kept safe from lay-offs and austerity measures and tuition reimbursements can be issued.

The consequences cannot be overstated: universities are closing doors for two weeks to stop the spread of COVID, leaving students in the dark about their futures on campus. Others are staying closed and refusing to offer tuition refunds to students should they have to leave. Students already had to sue for refunds after universities refused refunds in the Spring semester, after closing and leaving students in out on their own.

Yet others, at the complete detriment to the student body, are trying to open once again. “Just days after classes resumed, Wisconsin recorded its highest number of coronavirus hospitalizations yet. This left many puzzled by the return to in-person instruction when the situation in the area was only worsening. Moreover, continued the decision to stay open conflicts with the county leadership’s request for the university to move online. The university’s choice demonstrates behavior that contradicts both public health and politics, with a heavy focus on its consumers, the students.”

And students that do test positive for the coronavirus are experiencing an ever-worsening lack of support from the university. Isolation in a specific dorm, no contact with anyone, and half-hazard meals prepared that cost students thousands of dollars extra in their tuition. One student that tested positive and was quarantined experienced isolation and a lack of care, “Besides my test at campus health, every one of my interactions was held over the phone. Students in quarantine were given one bag meal a day, which mostly consisted of snack foods, but we also had three bottles of water and one hot meal.”

All the testing, the contact tracing, the quarantines, and isolation make it clear that online learning was the optimal solution for students this semester. But because online learning wouldn’t have been a justifiable learning apparatus for students that costs tens of thousands of dollars each year, or the extra money that it costs for students to live and eat on campus as well. We have to acknowledge the corporate model of university life—increasing profit margins, increasing costs—has not and will not work during an epidemic. It’s time to prioritize the health of the students and faculty, move the students to online learning.

And cut tuition rates.