The Washington Post reported that more than 8 percent of individuals held in migrant detention centers have contracted the coronavirus, proving that ICE is the super spreader agency. This update comes months after aCongressional Oversight Committee found that migrants died after receiving inadequate medical care in detention centers. In fact, in 2020 ICE detention centers had the highest annual death toll of people in ICE custody since 2005, with 21 deaths—8 of which were caused by COVID-19. Just this week, 47 children tested positive for coronavirus at a temporary migrant facility in Long Beach. Overall, deaths in detention have increased sevenfold since 2018, despite a marked decrease in the population of migrants living there.

Why is ICE the super spreader agency? Why is ICE unable, or unwilling, to protect the health of migrant detainees? The state of COVID-19 in prisons, jails, and detention centers is an illustration of state necro politics at work. Achille Mbembe describes necro politics as, “the use of social and political power to dictate how some people may live and how some must die.” This framework questions: Who lives, who dies, and how are state actors implicated in the outcome?

In the US, the pre-existing structural vulnerabilities faced by migrants are compounded by statuses of illegality that further restrict access to healthcare and community-based services. In detention, migrant health is deprioritized due to their criminal status. The state weaponizes social notions of (il)legality by asserting visibility or invisibility, presence or absence, according to its interests. In the case of transnational migrants, the state’s absence is felt through neglect and invisibility, ignorance and intentional abandon. ICE enforces large-scale detainment while failing to account for the health and safety of those confined.

Clearly, carceral spaces are particularly susceptible locations for COVID-19 transmission. And yet, ICE continues to detain migrants in large numbers. The agency does not even have enough spaces in detention for all the migrants it imprisons. Overcapacity further complicates health promotion measures, especially in relation to COVID prevention. A lack of resources leads to inappropriate medical responses to health emergencies. The underdevelopment of medical capacities and frequent documentation of “health emergencies” in detention proposes the question: Does ICE even try to protect migrant health and limit COVID-19 transmission? If it really intends to protect migrant health, wouldn’t the logical approach be decarceration? After all, incarceration is the antithesis of social distancing.

Migrants in detention are subject to intersecting sources of acute violence: the violence of COVID-19 and exposure to illness are compounded by the violence of incarceration. The inability to exert bodily autonomy—to isolate, protect, and remove oneself from sites of COVID-19 exposure—is another source of violence. The fear of potential exposure to the virus, without any way to fully protect yourself, is paralyzing. Despite being the most recent and publicized threat to migrant safety, COVID-19 exposure is just one danger to migrant health. Suicide rates continue to rise in detention centers. Research shows that detention centers are dangerous for women’s health and rights. Trans women are particularly vulnerable to abuse, illness, and death in detention centers. Why is the criminalization of migration prioritized over the safety of migrant bodies?

The dehumanization of migrant communities correlates to their danger in detention. Each day, new facts and statistics regarding a rising number of migrants crossing the border arise in the media. A “number of unaccompanied children,” “US border surge,” or a new “wave of migrants” are coming to the US in “record” numbers. How does our rhetoriccontribute to the dehumanization of migrants? Should we use these words to describe human beings? “The rhetoric framing immigration prisoners as criminals disassociates prisoners from those who may influence their wellbeing, leading to treatment of confined migrants as dangerous and disposable.” Through this rhetorical process, the state “creates illegality,” inviting mistreatment and exclusion for a community depicted as criminal.

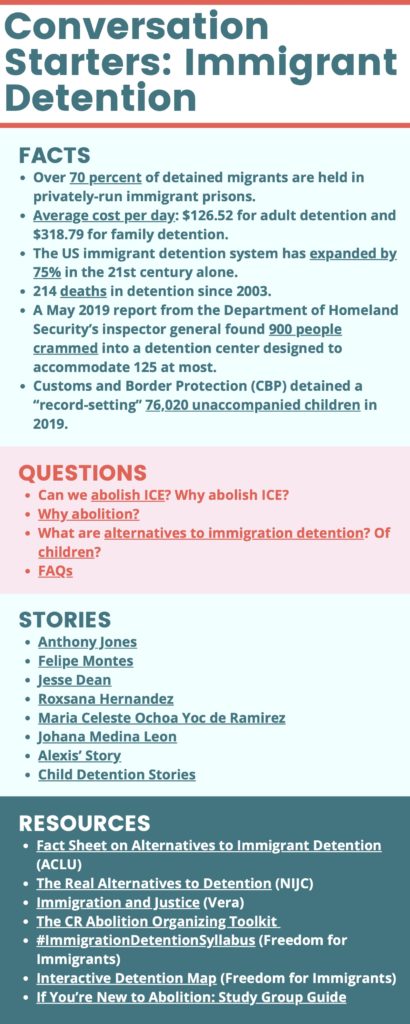

This rhetorical framing manifests in the poor quality of care and abuse prevalent in detention centers. How much more compelling is it to describe a “wave of migrants” as a “group of persecuted, oppressed vulnerable men, women, and children seeking economic, social, and political security from a neighboring country”? Perhaps even this description fails to sensitize opponents. Nonetheless, it is our responsibility to put names to the “waves” and “surges” in an attempt to acknowledge the grief experienced by communities of color across the United States—migrants whose loved ones were not “martyrs” but casualties of state policy and carceral beliefs: Anthony Jones, Felipe Montes, Jesse Dean, Roxsana Hernandez, Maria Celeste Ochoa Yoc de Ramirez, Johana Medina Leon, and many more.

(By Alex Groth: Alex Groth, a young advocate, is passionate about deconstructing migrant detention centers and promoting safer, more dignified alternatives to incarceration.)

(Image Credit: Alex Groth)