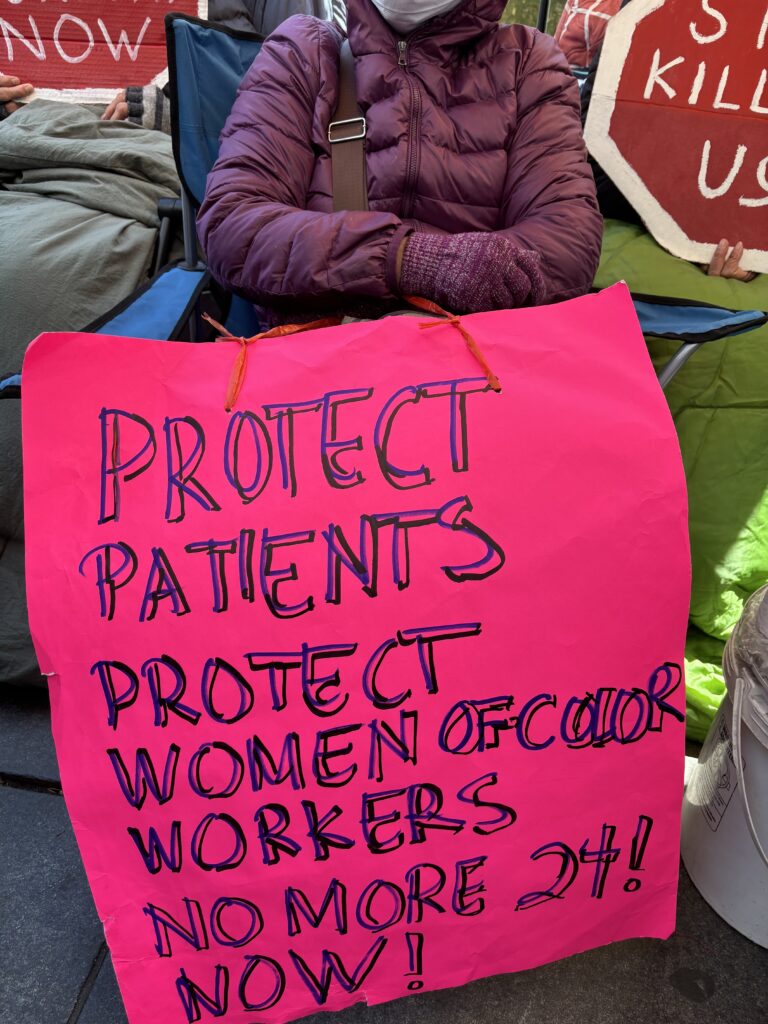

It is the third day of the hunger strike outside City Hall in New York City, March 22, 2024. I emerge from the subway into the brisk chill of Spring. Although the buds have begun showing on the trees, the hunger strikers and those who have gathered are bundled up in winter gear, holding up signs and chanting, “No More 24,” “Stop the 24-hour Workday,” and “Speaker Adams Give Back Our Health.” The home care workers “demand that the union stop its collusion with home care agencies and insurance companies to maintain the racist, sexist, and unjust 24-hour workday.” Bill 0615 has been introduced to the City Council demanding a ban to the 24-hour shift and cap the shift to 12 hours.

For the last several years Ain’t I a Woman campaign has been advocating for the home health aides with City Council for an increase in wages as well as for reasonable hours with breaks. While wage increase to $18 an hour has been honored, the pay covers only 13 of the 24 hours, which means the home health attendants are exploited and the city owes them back pay for the hours of overtime. The current inflation demands an even further increase of the minimum wage.

Many of the strikers speak Mandarin. So the speakers at the rally organized by Ain’t I a Woman Campaign have translators who summarize their speeches, translating them into Chinese for the workers. I know that there are other immigrant workers there as well, but I don’t meet them today. I meet organizers from National Mobilization Against Sweatshops, Socialist Democratic Party, Gabriela (a Filipina feminist organization) to CROC (a group of retirees fighting the City to protect their health benefits), and others.

The strikers sit in the shadow of City Hall Park, under umbrellas, a meager protection from the wind and the impending rain forecasted for the next day. Some of them mingle with the gathering to speak and then go back to their chairs to rest. It takes a lot of energy for them to answer people who interview them with the help of translators, since they have been subsisting on just water, Gatorade and broth. We are assured that the strikers have been evaluated by doctors before the strike and the doctors are on call during the 5-day strike to check on them.

I am out here in NYC on this third day of the workers’s hunger strike because I am from Suffolk county, Long Island where many of the workers live since it is unaffordable to live in Manhattan. The faces of workers sitting on the lounge chairs light up when I say I am a writer. They also connect with me as a fellow immigrant. They gesture that I should write about the strike.

I speak to Lai Yee Chan and Ling, two middle aged women, who have placed their chairs on the subway grates to get some warmth. They say that the 24-hour shift has been extremely strenuous on their bodies. My friend, Susan, asks them through an interpreter if they need any supplies. They say they cannot eat anything. She says, “I mean, like gloves or lotions or scarves.” They shake their heads. One of the organizers, Kaitlyn, says she is collecting supplies and tarps are essential as rain was expected the following day. I worry about the women gathered in the cold and if they would get sick being out in the dampness of night. How can the tarps really protect them? I speak to Alee through an interpreter. She says she works for more than 24-hour shifts, sometimes 48 hours straight with barely 2-3 hours of sleep. “My back hurts. I take care of an old couple and it is hard to do the work without rest.” She means that taking care of old patients requires lifting them for some of their needs. She continues, “I cannot see my grandchild. I miss out on being with him.”

I speak at the rally organized by Ain’t I a Woman campaign. I say that a hunger strike is serious. It means that these workers are willing to put their bodies on the line to fight for humane working hours. How can a 24-hour shift be acceptable in a country that believes in equity and is the richest in the world? And most of all, these are immigrant women who are being discriminated against, both as women and as people of color. Their work of taking care of patients is devalued just as their bodies are devalued. If the health of a patient is important, then shouldn’t the health of a care worker be vital? I talk about my experience of hiring home health aides for my disabled mom in Chennai, India. The organization that set up the aides were very clear that they had to work in 12-hour shifts with mandated breaks and a fair pay that was commensurate with the cost of living. I said that I encountered justice in work hours and pay in a country that is called a developing nation. So, reasonable hours can definitely be worked out in the New York, if there is political will.

We are gathered to rally with the hunger strikers to push for that political will to manifest. Before I speak, I hear a professor explain the value of hunger strikes and how globally activists have had to go hungry to be able to get their governments and lawmakers or other administrative body to hear their demands, and she cites Dalit activists in India most recently who have been on hunger strike to fight policies that are unjust. I think of the strike that became internationally known, of Rohith Vemula, a Dalit student in the University of Hyderabad who went on hunger strike to demand that the university not dock his allowance because he was part of the Ambedkar Students Association.

Will Council speaker Adrienne Adams come around to accept the workers’ demands? The strike ends on Sunday, March 24. Then what? We have yet to see what the outcome is for the workers. I will say that participating as a witness to this strike has been a political lesson for me about the position of women’s labor in the workplace, about the boldness of women workers whose bodies have been hurt by the 24-hour shift but are willing to fast putting their bodies at further risk, so they and other women do not have to suffer the inhumanity of one, two, or three-day shifts and that, too, without compensation and at the cost of their health. I learned about the difficulty of getting government to hear the workers’ demands, despite the involvement of a well-respected union. Will bill 0615 be passed? Let’s see.

( by Pramila Venkateswaran: Pramila Venkateswaran is a professor at Nassau Community College and is also a feminist activist, a poet and a scholar. She is the President of the Suffolk chapter of the National Organization for Women.)

(Photos by Pramila Venkateswaran)