Standing outside a Virginia courthouse, waiting for justice

“If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention”

Heather Heyer

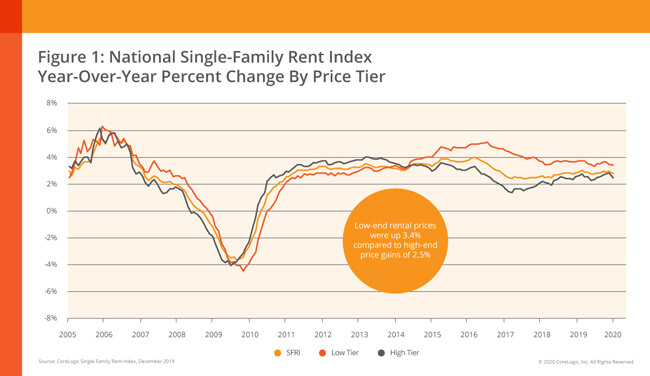

The pandemic turned the economy upside down and inside out, or so we are told. We are also told, still, that `we are all in it together’. Welcome to the place where the theater of cruelty merges with the wretched of the earth, and, through the cataclysmic changes, the worst remains the same and absolutely ordinary. We are talking, once more, of eviction. Two reports appeared today, both focusing on Georgia. In one, we learn that, among African Americans, youth and housing insecurity are primary causes of “vaccine hesitancy”. In the other, we learn that, in the Atlanta metro area, evictions are concentrated in low income and Black, Indigenous, People of Color, BIPOC, neighborhoods. At one level, we learn that we have learned nothing, since, as both reports suggest, these patterns preceded the pandemic and have `simply’ continued. What are we to do with that `simplicity’, with the persistence of systemic racism in the real estate industry as in the courts? And what is to be done?

According to a study of “vaccine hesitancy” among African Americans in Georgia, “COVID-related housing insecurity—difficulty paying the rent or mortgage or even eviction—increased the odds of vaccine resistance sevenfold”. Actually, housing insecurity increased those odds by 7.3-fold. Why does housing insecurity increase those odds so dramatically? According to the report, those living with `housing insecurity’ tend to live in highly segregated neighborhoods, are low wage essential workers, and have little to no access to health care systems. They’re not `hesitant’, they’re excluded. For “highly segregated neighborhood”, read “ghetto”. For “low wage essential worker”, read “indebted servant” or, better, “serf”. Again, that’s not hesitation. That’s feudalism.

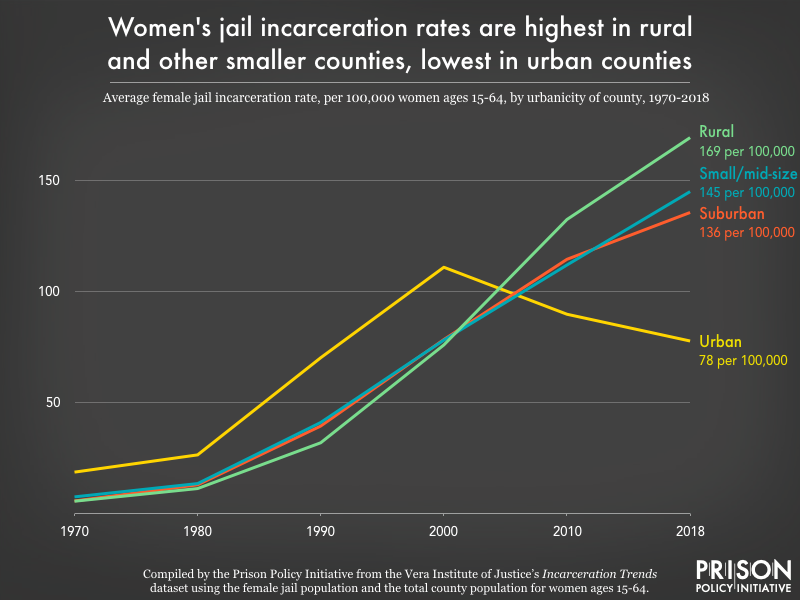

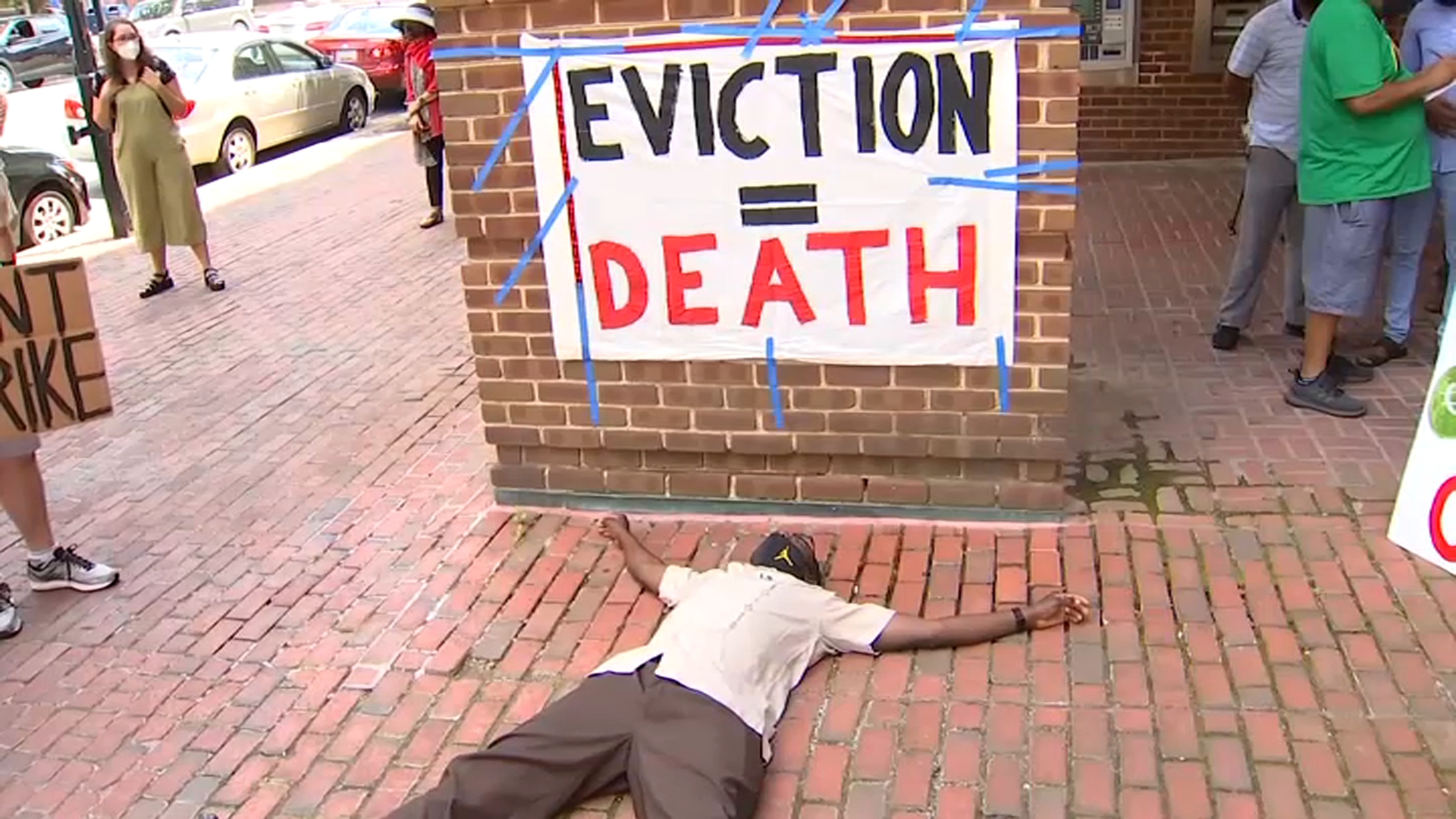

According to the second report, five counties make up 63% of the Atlanta metropolitan area population and 74% of its occupied rental units. During the pandemic, eviction filings continued, especially in “hotspots”, census tracts that were below 80% of the Area Median Income, or AMI, and were 50% or more Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. These hotspots were not a surprise to the researchers, since, prior to the pandemic, the same neighborhoods were eviction hotspots and the same patterns devastated those neighborhoods, communities, families and individuals. As the authors note at the outset of their report, “An eviction marks a crisis point of housing instability that ripples into nearly every facet of a person’s life and harms future chances of housing security …. With the added urgency of a global pandemic, the impacts of eviction mushroom and tighten the nexus between individual outcomes like an eviction and community-level harm.” In the Atlanta metro area, as across the United States, evictions are working as planned, condemning majority BIPOC communities, especially low- to moderate-income BIPOC communities, to a certain death sentence. None of this is new, even if its context makes it seem worse than before.

We “learn” this week that in Virginia, the Virginia that has improved on its shameful history of mass evictions, high eviction rates, and easy eviction procedures, in that Virginia, “Black women … are disproportionately evicted.” We “learn” this week that in New York, the New York that only recently started distributing any rent relief funds, Black women make up nearly two-thirds of those applying for rent relief. Again, that relief has only now started, barely, reaching people.

In light of the new CDC Eviction Moratorium, and the challenges to it which are currently being argued before the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court that barely kept the last CDC Eviction Moratorium going and, with a single vague sentence, tried to gut the New York State Eviction Moratorium, the Eviction Lab took a look at the first iteration of CDC Eviction Moratorium. Here’s what they found: “A large number of eviction cases originate from a relatively small number of Census tracts … Neighborhoods with high eviction filing rates prior to the pandemic continued to see the highest rates during the CDC moratorium … Neighborhoods with high eviction filing rates prior to the pandemic continued to see the highest rates during the CDC moratorium … Prior to the pandemic, Black renters received a disproportionate share of all eviction filings: they made up 22% of all renters in ETS sites, but received 35% of eviction filings. They continued to be over-represented during the CDC moratorium period, receiving 33% of filings.”

What they found is that we have learned absolutely nothing. Where is the outrage at the predictability of these findings? Around the country, activists are pushing, often with success, for right to counsel, where every tenant would have an attorney present and engaged, long before every going to court; Just Cause restrictions, which would require that landlords give just cause before not renewing a lease; sealing eviction records; mandatory mediation; and more. Those are all important policies. At the same time, we have a reckoning due. Where is the outrage at the loss of life, the devastation, the twenty first century version of feudalism? Why does it take a plague for people to begin paying attention to our neighbors, and have we actually begun paying attention, if, in the end, each study concludes that the present and the past are one and the same.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: ABC News / AP / Ben Finley)