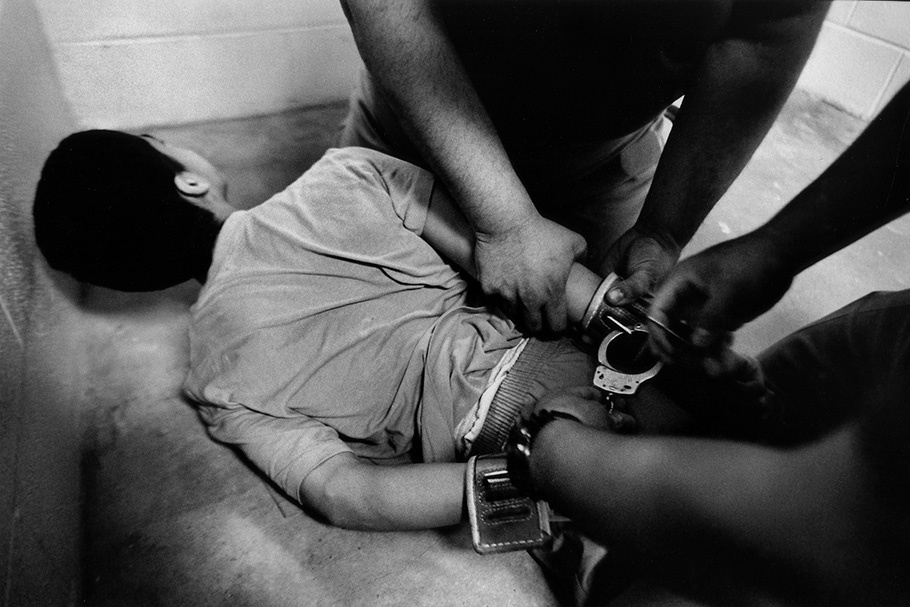

Wrongly convicted of capital offense, MK spent six years in a small, dirty cell, which had a capacity of 300, then housing no less than 1400 inmates

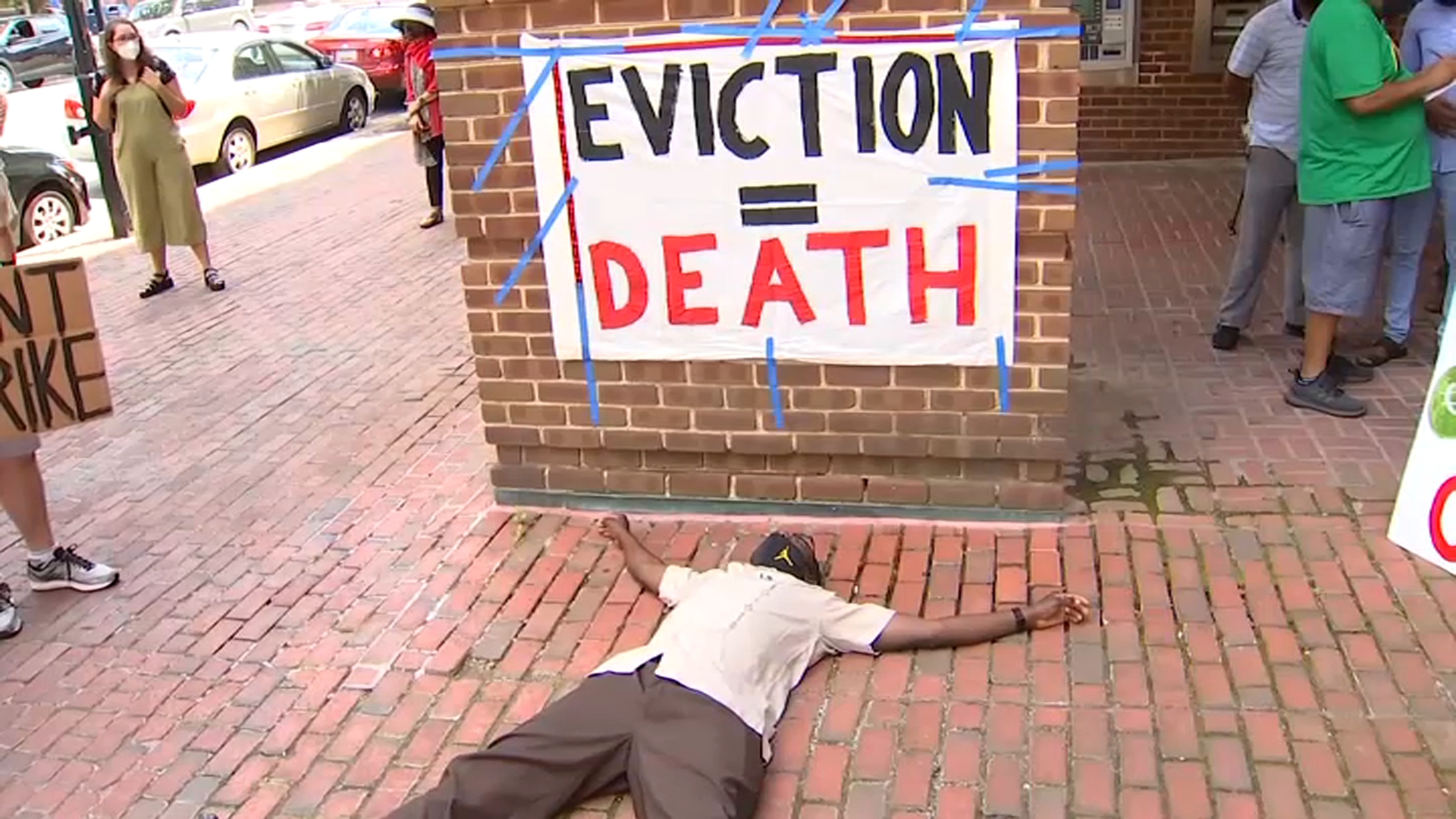

On Friday, July 23,2021, Sierra Leone’s Parliament voted unanimously to abolish the death penalty. Unanimously. While the outcome was pretty much expected, the unanimity of Members of Parliament is worth noting and celebrating. Parliamentarians joined advocates and others in decrying the inhumanity and barbarity of executions and of the entire apparatus attached to the death penalty. Equally, Members of Parliament joined advocates and others in declaring that vote to end the death penalty was another phase of the decolonization project. As Sabrina Mahtani, co-founder of AdvocAid, a leading Sierra Leonean organization opposing the death penalty, noted, “The death penalty is a colonial imposition, and these laws were inherited from the U.K.” It’s time, it way past time, for all those who suffered colonialism, who continue to struggle with the legacy and imbedded consciousness of colonialism, to decolonize, to abolish the death penalty and much more.

Sierra Leone is very clear about at least part of the “much more”. In principle, Sierra Leone has stopped executing people since 1998, but it has continued to segregate those convicted of capital offenses to death rows, where they sit and wait … for nothing or worse. Along with eliminating executions, the new legislation eliminates mandatory life sentences. This is particularly important for survivors of sexual violence, predominantly women and girls. According to Sabrina Mahtani, “This will allow judges to have judicial discretion to take into account all the circumstances of a case, such as a history of gender-based violence or mental illness, and hopefully prevent the injustices that have happened in the past.”

Since its founding in 2006, “AdvocAid has actively campaigned for the abolition of the death penalty and provided free legal representation for women and men on death row to challenge their convictions and death sentences. AdvocAid has secured the release of six women and three men on death row through appeals or presidential pardon applications.” Here’s the story of one of those women, call her Aminata.

In 2009, Aminata was a 17-year-old girl living in Kenema, in the eastern part of Sierra Leone. She was an orphan who had little or no formal education and could not read or write. She had been in a relationship with someone who was abusive, and so left him. Or better, she left the relationship. The young man was the son of the landlord of the compound in which Aminata lived, and so, despite her having ended their relationship, what did not end was the physical violence. He continue to beat Aminata. Finally, one day, while being beaten with a rubber pipe, Aminata picked up a knife and defended herself. She was arrested and tried … sort of. Sort of because, although Aminata was 17 years old and therefore a juvenile, she was tried in adult court because [a] she had no birth certificate and so [b], despite her protestations, the police registered her age as 18. Aminata was shipped off to the maximum security prison in Freetown. In 2010, Aminata was sentenced to death. AdvocAid appealed. The case was not heard for another four years: “Finally, 9 years after she was sentenced to death, her appeal was granted and her sentence was quashed …. Sadly Aminata’s story is not uncommon.”

While the British were not the first to conduct executions on African soil, they did bring and institutionalize the notion of “capital punishment … as not just a method of … punishment, but an integral aspect of colonial networks of power and violence.” As Aminata’s story shows, those networks of power and violence continue, in Sierra Leone as elsewhere, until they are rooted out. AdvocAid’s Legal Manager, Julia Gbloh said: “The death penalty is the act of legalizing murder and its abolishment highlights a new dawn in our nation.” It is a new dawn for Sierra Leone and hopefully for the world, including the United States. As Sabrina Mahtani explained, “Here’s a small country in West Africa that had a brutal civil war 20 years ago and they’ve managed to abolish the death penalty. They would actually be an example for you, U.S., rather than it always being the other way around.”

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: AdvocAid)