“The mainstream has never run clean, perhaps never can. Part of mainstream education involves learning to ignore this absolutely, with a sanctioned ignorance.”

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason

Across the United States and around the world, evictions are rising and residential rentals and home sales prices are skyrocketing. Predictably, this is accompanied by rising rates of eviction. While parts of the United Kingdom are experiencing rates of eviction they haven’t faced in almost twenty years, the United States is facing mortgage rates it also hasn’t faced in over twenty years. But what exactly is an eviction, other than an existential crisis, a crisis that in the United States targets Black and Brown women? In the official discourse on housing, eviction has meant “the action or an instance of expelling a person by legal process from land, property, etc., occupied by him or her.” The key here, and the element of sanctioned ignorance, is “by legal process”. If eviction is only an action based on a legal process, what then do we call all those actions in which people are forced to move, but without any legal process involved?

Consider these stories from the last couple days.

In Sausalito, California, the owners of an apartment complex occupied mostly by elderly residents recently issued eviction notices to all the residents. The all-too-familiar story is a new owner came in a year or so ago, began letting maintenance go, never answered calls for repairs and then, again this week, decided the buildings needs “remodeling”. And so … people on fixed incomes in a hot rental market are out on the streets.

In Bakersfield, California, rents are going up as much as 40%, often in violation of the law. When Bakersfield Tenants Union Founder Wendell “J.R.” Wesley Jr. was issued a $100 rent increase, he knew that was illegal, and so went to the Leadership Counsel, a local advocacy group, got some help, and stopped the rent increase as well as the threat of eviction.

In Tucson, Oklahoma, a recent survey of unhoused people showed that the population of homeless elders is rising precipitously, and that the two leading causes of homelessness are eviction and skyrocketing rents.

These are just three stories from the last couple days, taken from a much longer list. They are stories of eviction, and familiar ones at that, but they hide as much as they show. What about all the elders living in apartments where the writing is on the wall, sometimes in the form of unattended mildew and mold? What about the elders who are harassed, directly or through `passive’ nonresponse and inaction, into `informal eviction’ or, even more ineptly, `self eviction’? Likewise, J.R. Wesley is an organizer who knows more than a thing or two about local and state housing laws. What about all those people who received a $100 increase in their rent, didn’t know it was illegal, didn’t know there are organizations and resources to help them, and moved before they lost everything and incurred today’s version of a Scarlet Letter, ie an eviction filing? Finally, it’s not only evictions leading to homelessness. It’s also rents rising so fast and so much they become unaffordable. People who have lived for years in an area that was affordable, if barely, are now forced to move through no action or fault of their own. What about them?

In Wisconsin, the Supreme Court will hear an argument to reduce the time eviction records are kept from 20 years to one year. In Wisconsin, the 20 years on file is for eviction filings, not evictions, and so the landlord has an extraordinarily menacing tool: “The vast majority of renters in eviction court are not evicted. According to the petition, there were 17,727 eviction filings in Wisconsin in just 2021. Just under ten percent of those eviction filings actually resulted in an eviction”. What about all those people who understand that an eviction filing is as damning as an actual eviction and decide to move?

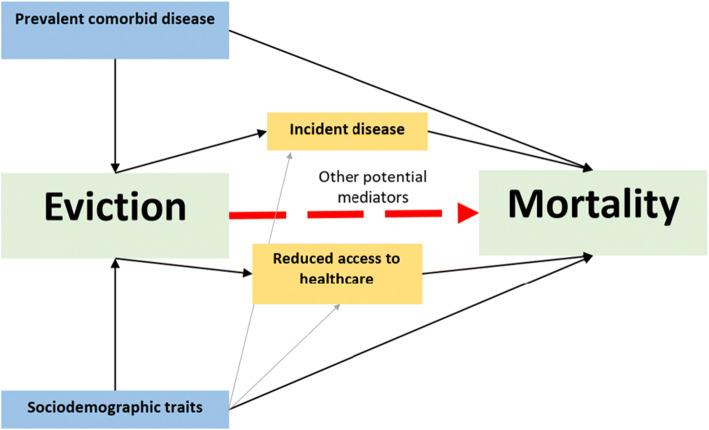

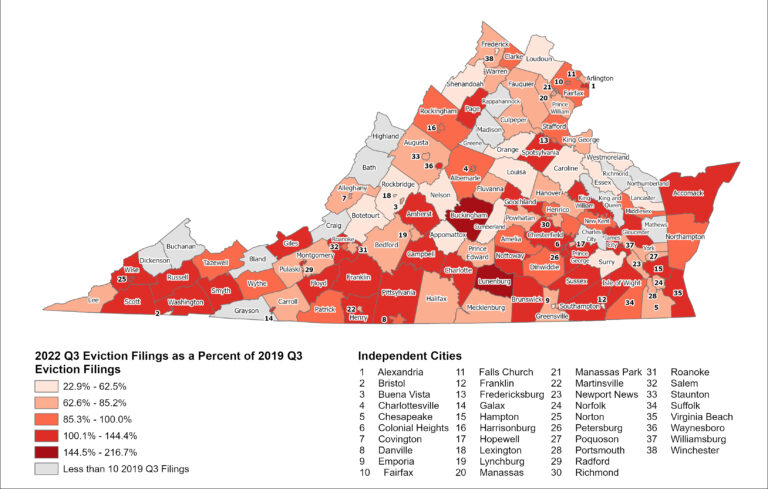

That more attention is being given to eviction is good, but we need more and better attention. At this stage, there is still no national eviction data base. Last month, Virginia began collecting data on the number and locations of evictions that occur in any given year. That’s a good step. Across the country, many groups follow the model of Princeton’s Eviction Lab and collect data on eviction filings, also an important step in the right direction. But, again, those who are formally filed against, and even more those who go through the tragedy and existential crisis of eviction, are a minority of those who have been forcibly displaced. And we know, from history as well as from contemporary experience, that forcible displacement, while it may be experienced in deeply individual ways, is never a solitary event. Forced displacement is always already mass displacement. We cannot, in our research, advocacy, and organizing, create yet another mainstream moment, in which millions of people and communities are relegating to the status of ghosts, present and yet somehow not sufficiently enough to matter.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo: Iziko Slave Lodge)