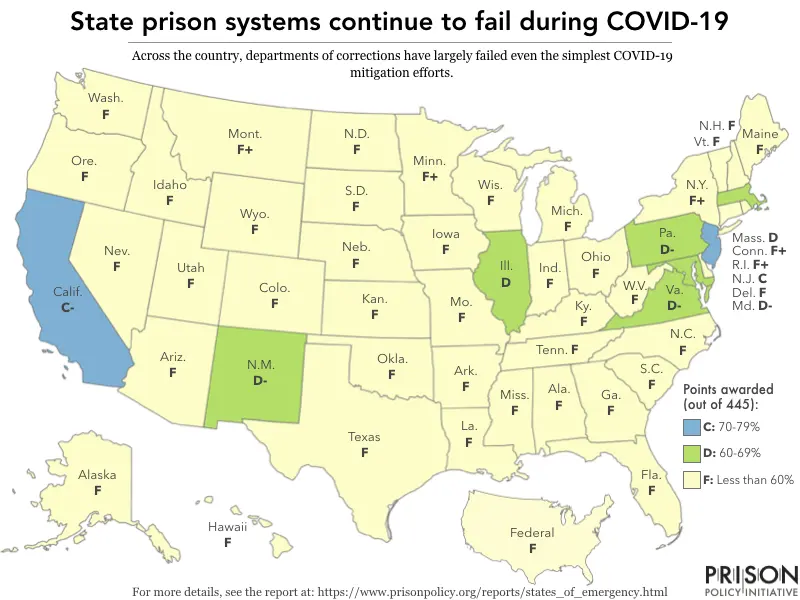

In June, the Florida Department of Corrections ended all Covid-related pandemic emergency protocols. This includes reporting, and so now, although cases increase and people behind bars are dying, the state issues no reports. It’s none of your or our business. Go away. Florida is not an outlier. The whole country has refused do care for people behind bars. According to the most recent Prison Policy Initiative analysis, the United States gets an F, the Federal Bureau of Prisons gets an F. 42 state prison systems get F or F+. The highest grade went to New Jersey, C. Another study, looking at jail populations, finds that one of the best forms of Covid mitigation – along with vaccination, mask mandates, social distancing – is jail decarceration: “The globally unparalleled system of mass incarceration in the US, which is known to incubate infectious diseases and to spread them to broader communities, puts the entire country at distinctive epidemiologic risk …. Public investment in a national program of large-scale decarceration and reentry support is an essential policy priority for reducing racial inequality and improving US public health and safety, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity.” As to immigrant detention centers, “The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has proven itself ill-equipped to manage the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in its detention facilities.” This applies as well to the “nongovernmental detainee facilities across the country”, such as the Otay Mesa Detention Center, site of the largest Covid outbreak among detained migrants … thus far. Say what you like about Florida, when it comes to concern for the vulnerable, for care of those people living and suffering in prisons, jails, immigrant detention centers, it’s just one of the guys.

As the Prison Policy Initiative analysis suggests, this shouldn’t have been so complicated or difficult. Reduce the prison population. Reduce infection and death rates behind bars. Vaccinate everyone living behind bars. Address basic health and mental health needs through easy policy changes: waive video and phone call charges; provide masks and hygiene products; suspend medical co-pays; require staff wear masks; require staff be tested regularly. That’s it. It’s not complicated. It’s not hard. Everyone failed. I know … New Jersey got a C, California a C-Everyone else got a D or F.New Jersey vaccinated and released many living behind bars, but New Jersey’s infection rate in prisons was almost four times higher than the state COVID infection rate, and the prison Covid mortality rate was almost double that of the state.

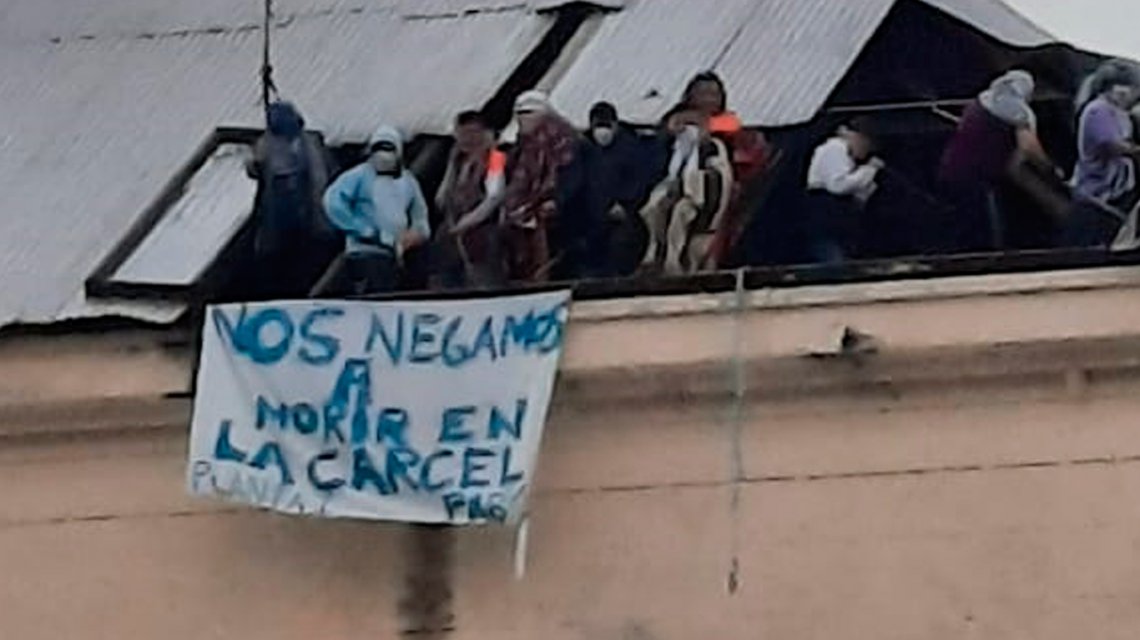

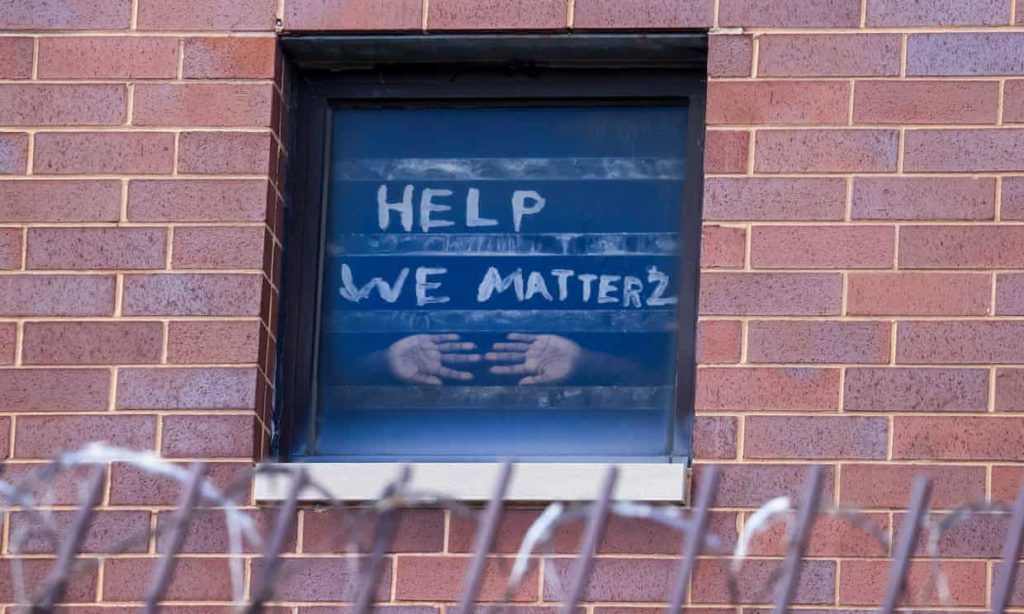

Four states – California, Illinois, Pennsylvania, New Jersey – made significant efforts to reduce prison population, partly through early release, early medical parole, suspension of incarceration for technical violations of probation and parole. Even with that, no state actually passed: “the nation’s response to the pandemic behind bars has been a shameful failure.” The response is shameful because there has been no response, and here I don’t only mean on the part of prisons, jails, immigrant detention centers. Where is the outrage? Where is the attention? Other than the usual suspects, who really cares? The failure is shameful because it is part and parcel of the national project. This is us, brutal and bankrupt in our lack of concern.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Infographic Credit: Prison Policy Initiative) (Photo Credit: The Guardian / Tannen Maury / EPA)