What happened to Shaylene Graves? She was “found” hanging in her cell at California Institution for Women, or CIW. Given the situation at CIW, what happened to Shaylene Graves is nothing out of the ordinary. Last July, California Department of Corrections officials “discovered” a crisis. In the previous eighteen months, four women prisoners at the California Institution for Women, or CIW, in Chino killed themselves … or were killed by willful neglect: 31-year-old Alicia Thompson, 23-year-old Margarita Murguia, 73-year-old Gui Fei Zhang, and 34-year-old Stephanie Feliz. After Feliz’s death, fellow CIW resident April Harris wrote, “We have women dropping like flies, and not one person has been questioned as to why … I have been down almost 20 years and I have never seen anything like this. Ever.” The suicide rate at CIW is only exceeded by the rates of attempted suicide and self harm. What happened to Shaylene Graves? Just another death in the hellhole California Institution for Women.

According to Victoria Law, “Graves’ death is the latest to rock CIW, which is currently at 135 percent capacity: 1,886 women in a prison designed for 1,398.” Shaylene Graves’ mother, Sheri Graves, wrote an open letter to the public concerning her daughter. The letter ends: “I got a call, `your daughter has died in custody.’ They said she was found hanging. My son said, `Shaylene would not hang herself. The officer said, `I know.’ The prison system failed my daughter. The prison system failed her son, Artistlee. The prison system failed our family, her friends and everyone she would have blessed with her vision for her organization. Most of all, the prison system had failed to protect her life. She lost her right to freedom in order to pay her debt to society. But, she wasn’t supposed to lose her right to life and protection while incarcerated.”

Shaylene Graves was a month from being released from CIW. According to all reports, she was a vivacious, engaged, sociable, charming, funny young woman. She was preparing to leave CIW, and to start an organization to help other women in their transition out of prison. She cared about her son, her family, her community. She cared about her sister prisoners, at CIW and elsewhere. Those who knew her are shocked by her death and deeply doubtful of the initial report of suicide.

Many are shocked, but the death of Shaylene Graves did not rock the Institution, no more than the prison system failed. The prison system did far worse than fail. It refused, and in so doing killed Shaylene Graves. Whatever “facts” or “details” emerge concerning the specifics of Shaylene Graves’ last hours on earth, the facts are that if it hadn’t been her, it would have been some other woman at CIW. The numbers bear that out. There is no surprise when an institution fails to address a suicide rate eight times that of the national rate for people in women’s prisons, when “suicide prevention” in the institution is consistently rated as “problematic”, when the answer to an overcrowded suicide watch unit is to shunt the “overflow” into solitary confinement.

The California Institution for Women is overcrowded, but so are the Central California Women’s Facility and the women’s section of Folsom State Prison. The overcrowding is worse at Central California, but the women there are not dropping like flies. Shaylene Graves requested to be moved from Central California to CIW, so as to be closer to her family. And now … she’s closer to her god, and her family grieves and rages and demands answers and, even more, demands justice. So should we all. We have had enough reports asking why are so many women attempting suicide at the California Institution for Women. We have had too many “discoveries” to claim any sort of innocence. Women are dropping like flies in the California Institution for Women because pushing women to drop like flies is more convenient than treating women as full human beings, more convenient than treating prisoners as full human beings, and a whole lot more convenient than treating women prisoners at all.

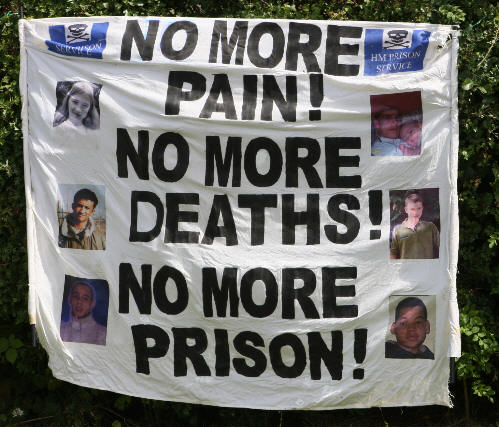

Women prisoners and supporters, such as the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, long ago identified the crisis. They have continually, loudly denounced the conditions and called for a thorough overhaul, beginning with releasing most of the prisoners. Three years ago, when women in the California Institution for Women participated in California’s statewide hunger strike, they called attention to the State assault on their bodies, minds and souls. They identified a crisis, and the State looked away, and instructed all good citizens to do the same. That was three years ago. It is September 2016, and the assembly line of women prisoner deaths is not slowing down. It’s time to smash the machinery once and for all. Do it in the memory of Shaylene Graves.

(Image Credit: San Francisco Bay View / California Coalition for Women Prisoners)