On Sunday, June 18, Charleena Lyles – 30 years old, Black, mother of three, pregnant, Seattle resident – called police to report a burglary. Two white police showed up. Soon after, those two police officers shot and killed Charleena Lyles. The next day, on the morning of June 19, I opened my local newspaper, The Seattle Times, only to see a defense of murder on the front page. The headline read: “Mother killed by cops had mental health issues, family says.” This was misleading, prejudiced, and unethical.

First it suggested immediately that having a mental illness is somehow justification for getting shot by police. Second, it bootstrapped its own twisted logic by misrepresenting the response of the family and their communications after the shooting. They have been extremely critical of the police response.

The real story is “Police kill a pregnant woman in response to her call for help.”

How can this happen, and why does it keep happening? Why do the police keep killing black people? How can local police kill not one but TWO Black pregnant women who called for help within the past 9 months?

The Times cannot continue ignoring these obvious questions. They should investigate and report truthfully and ethically, and stop trying to protect the murderers. When they do so, they are complicit in perpetuating these crimes.

Writing last week, the week before Charleena Lyles was gunned down, Seattle Times columnist Nicole Brodeur apparently made readers mad because of the same issues of racial bias and ignorance. In this instance, the racism was directed towards an entire neighborhood and community, Columbia City. Yesterday, Nicole Brodeur apologized. Unlike the lukewarm PR response The Seattle Times issued after reader complaints on the Charleena Lyles coverage, Brodeur’s apology seems heartfelt, sincere, and persuasive. But the apologies belie the problem at The Times. Where is the value in a newspaper that, by its own admission, “lacks sensitivity” in reporting matters of race and gender?

In her apology, Brodeur concluded, “In taking on the issue of crime and gentrification in a single column, I climbed the journalistic equivalent of an Olympic high dive and failed. I need more training … My editor recently asked me whether there was a project I wanted to work on, something long-term. And this just might be it: My own self. My own bias.” Should we all be so privileged to get paid for this work!

As a long-time subscriber and constant Times reader for my 28 years in the city, I’ve supported newspapers for their many virtues, and excused the occasional misstep. But these are not missteps, and are not occasional. The reporting on Charleena Lyles was no misstep. In these urgent times, I can no longer separate The Times from its functional perpetuation of the status quo.

If The Times editors, reporters, and columnists lack the training, skill, or vision to do good journalism, as The Times itself has admitted numerous times this week, they should not be supported. For that reason, I’ve cancelled my subscription to The Seattle Times, and I urge others to do the same.

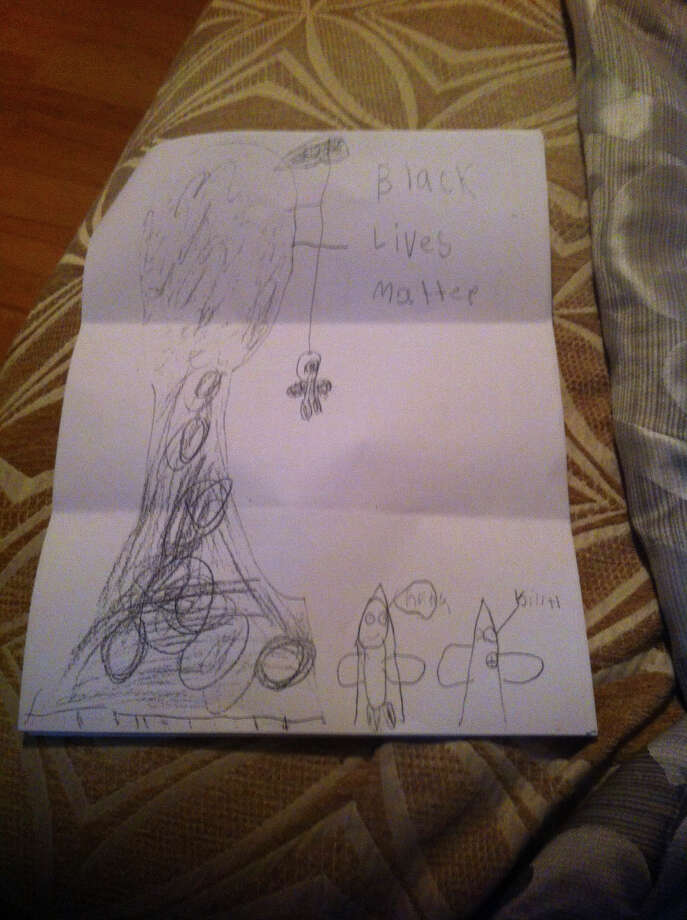

(Photo Credit: KUOW / Megan Farmer)