A new study came out this week that demonstrated that “tenants who were threatened with eviction experienced excess mortality that was ten times higher than that of the general population … People who faced an eviction filing during the pandemic died at over twice the rate that was normal prior to the pandemic.” While the majority of those facing eviction predictably lived in low-income communities, and more often than not communities of color, those who were threatened with eviction had a much higher mortality rate than their immediate neighbors who did not face eviction. We know, or we think we know, that eviction is an existential crisis. This study demonstrates that eviction filing, facing eviction, whether or not one is ultimately thrown to the streets, is itself an existential crisis. For many, an eviction filing like an eviction is a death sentence.

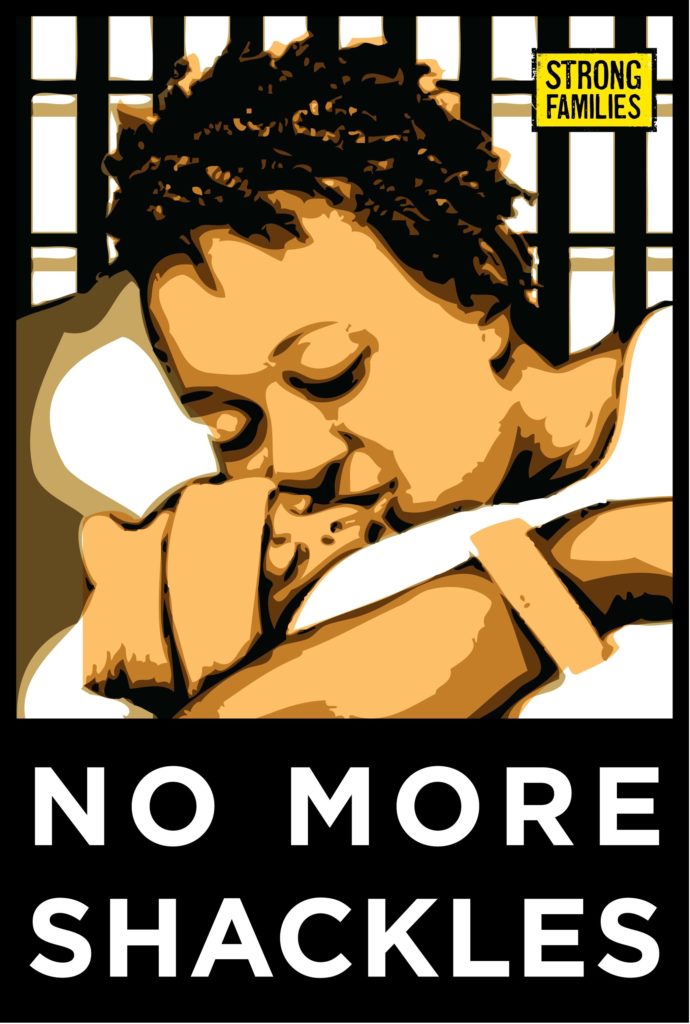

Where are the women in this toxic scenario? Everywhere, women are the very fiber of the story, of the situation. “The median age of the threatened renters was 36 years, 62.5% were women, 57.6% were Black, and their median annual household income was $38,000, with 25.9% living below the poverty line.” For Black women the arithmetic is particularly telling and lethal. While Black women make up 11.5% of renters considered, they comprised 38.7% of those who faced eviction filings, the highest proportion of any group. The study considered the first two years of the pandemic. During that period, according to the study’s authors, “if we had eliminated eviction filings altogether, more than 8,000 lives could have been saved.” What exactly is the value of a human life in the current housing market?

While, at some level, none of this is surprising, given the intersection of gender, race/ethne, class in the general eviction story, it bears emphasizing that the “mere act” of being threatened with eviction is tantamount to a death sentence. When you hear or read of the “eviction epidemic”, remember that that’s not a figure of speech. Evictions kill, eviction filings kill. Across the country, we see spikes in both eviction filings and evictions. Those are part of a national, and global, war on women, and in particular on low- to moderate-income women of color. Decent and secure housing is, or should be, a right. Safe and stable housing is life itself.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Images credit: Ariana Torrey / USA Today)