Welcome to the so-called `liberal’ DMV, DC – Maryland – Virginia. Yesterday, Maryland’s Republican Governor, Larry Hogan, vetoed a bipartisan bill that would have extended protection from eviction if the tenant has a pending rent relief application. That protection would have been a mere 35 days. The Governor also vetoed a bipartisan bill that would have required landlords prove their compliance with local rental laws before trying to evict a tenant. Who needs proof of compliance, when we’re talking landlords? These modest proposals were vetoed by the Governor because “Maryland already has some of the strongest tenant protection laws in the nation”. That’s a low bar, not to mention a lousy reason. On the same day, Virginia’s Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin vetoed bipartisan bills that would have assisted indigent public housing residents. The bills would have exempted very low-income tenants from having to pay exorbitant appeal bonds, which can run into the thousands, in order to appeal an eviction notice. The Governor explained that he preferred his vision, which was essentially to gut the entire bill and then claim victory. At least he didn’t claim Virginia already has some of the strongest protection laws in the nation. Both governors have national aspirations.

From Australia to the United Kingdom and beyond, the story is largely the same. Pandemic protections, such as they were, are coming to an end. The housing market, for purchase or rent, is hot and getting hotter. Landlords find, or create, loopholes in the already tattered safety net for renters. For example, across England and Wales, even weak restrictions on “no fault” evictions are blithely ignored. Of course, Parliament promised to and failed, or refused, to ban no fault evictions. This week, the New York legislature failed, or refused, to pass Just Cause eviction protections. Wages have not kept up with housing. Inflation is forcing low to moderate income families to decide among paying the rent or mortgage, putting food on the table, or paying for utilities. The affordable housing stock, already reduced after a decades’ long hiatus in construction, is being reduced. In many parts of the world, the mantra for those facing eviction is “Nowhere to go”.

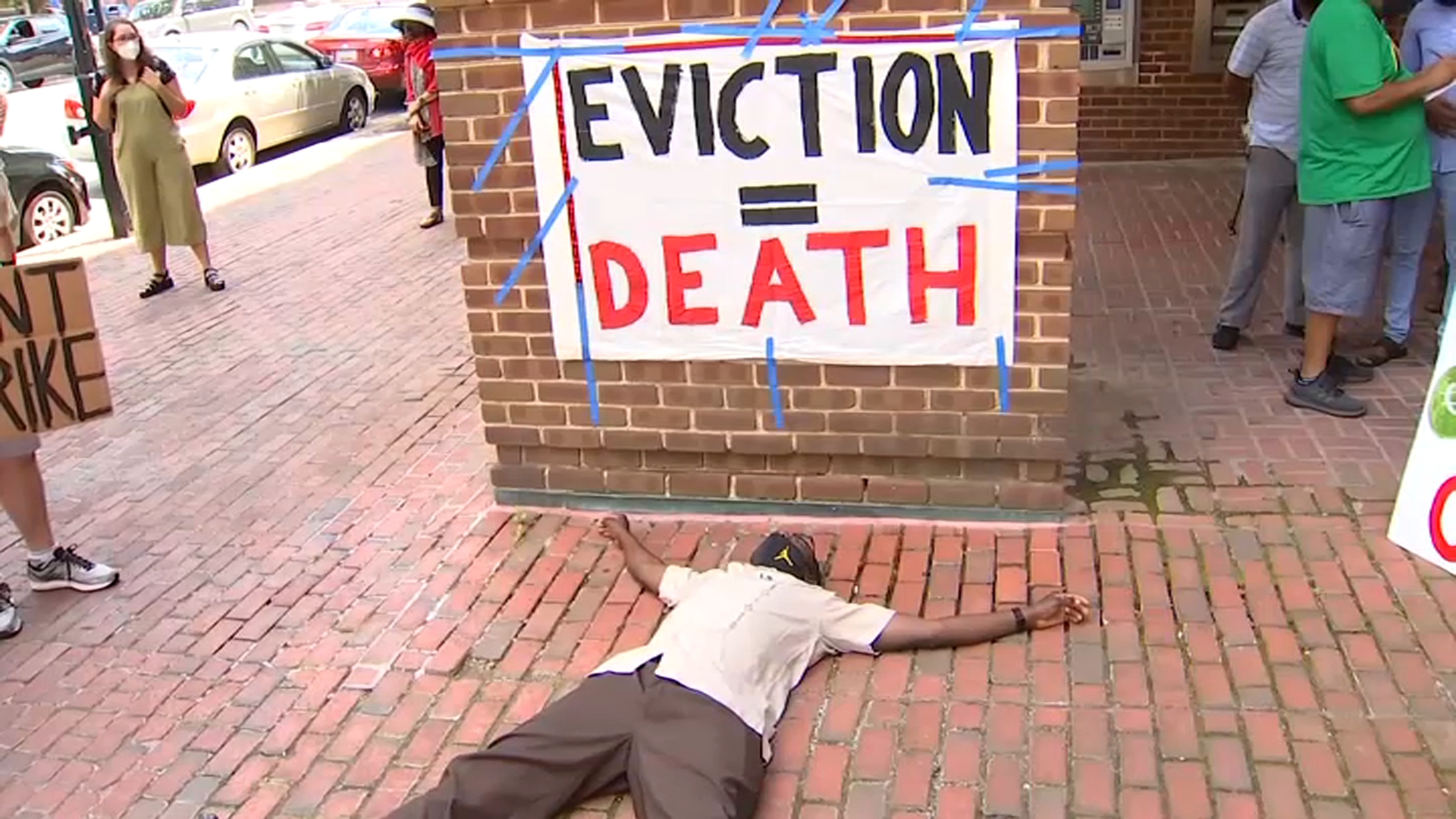

In New Orleans, eviction filings and evictions are rising rapidly. The explanation is rising rents and decreasing availability of affordable housing. Those are symptoms, not cause. Public policy is the cause. Look at any eviction court in the country. More than 90% of landlords have legal representation, fewer than 10%, often fewer than 5%, of tenants have lawyers. There are no scales of justice in that space. Only imbalance, inequality, injustice.

In Detroit, half the residents say their financial situation is more or less the same as a year ago, 23% say improved, 23% say worse. 35% of low-income residents say they are worse off now than a year ago. 33% of Detroit renters report spending 31-50% of their income on housing. 24% of renters report spending more than half of their monthly income on housing. According to the United State government, anything 30% or higher qualifies as “housing insecure”.

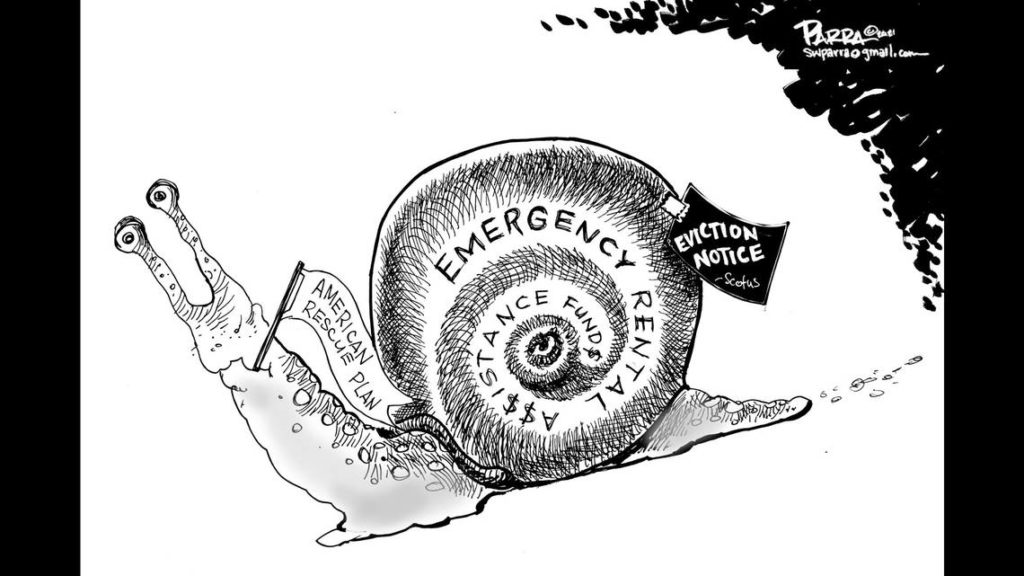

This is a brief overview of news of the last 24 hours. We entered the pandemic `discovering’ the lack of data. Individual organizations and people across the country created and expanded local eviction dashboards. There still is no national data bank. Courts remain spaces of collusion between judges and landlords. And the options offered by so-called leaders, with some exceptions, are either the protections in place are sufficient, when they clearly are not, or the protections in place or offered are excessive, when they are paltry. For too many, “return to normal” means nowhere to go.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: Max Becherer, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)