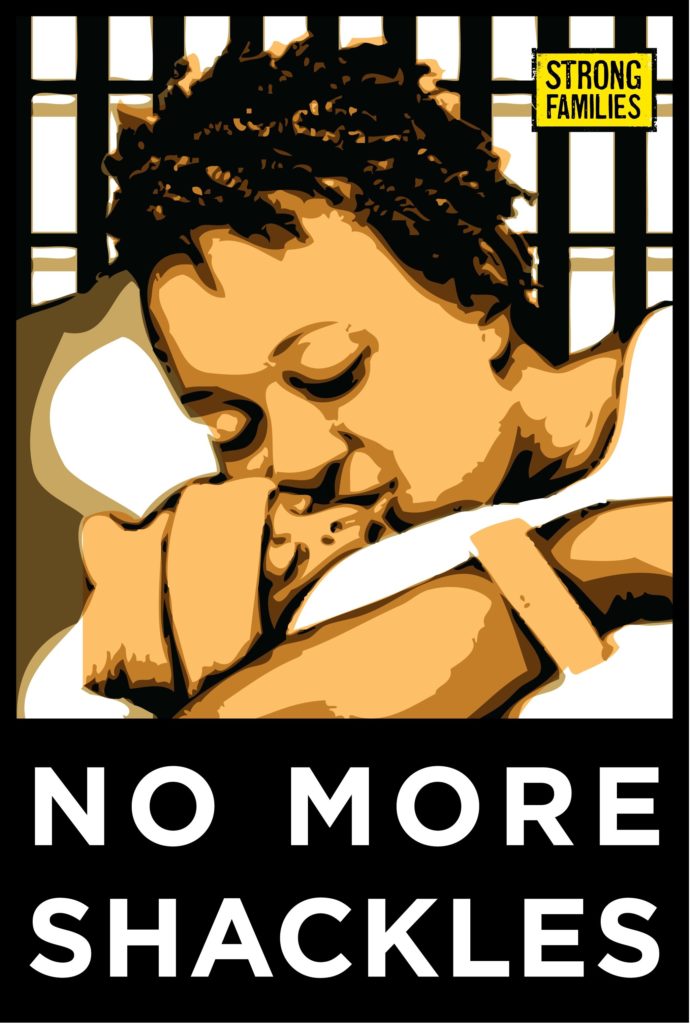

State legislatures in both Florida and South Carolina are considering bills that would outlaw shackling of women prisoners in childbirth. On one hand, it’s about time. On the other hand, which is the same hand, prison is so deeply imbedded into the fabric of the United States that questioning, much less transforming, any aspect of carceral practice requires a radical change in vision. As Angela Davis noted, in 2003, “The prison is considered so natural and so normal that it is extremely hard to imagine life without them.” So natural and so normal have prisons become in the national social landscape and consciousness that it is necessary to debate, at length, whether or not women in childbirth should be shackled. And so we wait attentively for the good news from both Florida and South Carolina.

Although federal law prohibits shackling pregnant prisoners, that law does not cover state and local prisons and jails, not to mention immigrant detention centers. Currently, 23 states allow for shackling women in childbirth. In a recent study of perinatal nurses who had cared for pregnant and postpartum women prisoners, nurses explained that the reason given for shackling women in childbirth was “adherence to rule or protocol.” When the nurses advocated for the shackles to be removed, the number one reason, by far, for denial was “rule or protocol.” In other words, the prison system has rules and protocols that say it’s ok to shackle women in childbirth, and so women prisoners in childbirth must be shackled. Period.

A different recent study of pregnancy outcomes in U.S. prisons from 2016 to 2017 concludes, “Being in prison or jail during pregnancy can be a difficult time for many women, fraught with uncertainty about the kind of health care they might receive, about whether they will be shackled in labor, and about what will happen to their infants when they are born. Some pregnant women in custody may experience isolation and degradation from staff and insufficient pre-natal care … Data from our study can be used to develop national standards of care for incarcerated pregnant women, advocate for policies and legislation that ensure adequate and safe pregnancy care and childbirth, develop alternatives to incarceration for pregnant women, pro-mote reproductive justice, and encourage broader attention to the reproductive health needs of marginalized women and their families.” As of now, there are no national standards of care for incarcerated women, and there is no requirement to collect data from prisons and jails, much less immigrant detention centers. In a world of intensive and extensive surveillance, prisons and jails constitute a black hole archipelago of opacity. For women, that means a world of pain and suffering.

Florida’s legislature is considering the Tammy Jackson Healthy Pregnancies for Incarcerated Women Act. Last year, Tammy Jackson gave birth, alone, in a cell in the North Broward Jail, in Pompano Beach. The law would ban shackling pregnant women prisoners; invasive body cavity searches; and the use of solitary confinement. It would also require medical examinations at least once every 24 hours.

South Carolina’s legislature is considering a bill that would ban the shackling of incarcerated pregnant women who are in labor. Additionally, the new law would restrict restraint of pregnant women prisoners to handcuffs only: “A person officially charged with safekeeping of inmates, whether the inmates are awaiting trial or have been sentenced and confined in a state correctional facility, local detention facility, or prison camp or work camp shall not restrain by leg, waist, or ankle restraints an inmate with a clinical diagnosis of pregnancy. Wrist restraints may be used during any internal escort or external transport. The wrist restraints shall only be applied in the front and in a way that the pregnant inmate may be able to protect herself and the fetus in the event of a fall. This provision also applies to inmates not in labor or suspected labor who are escorted out for Ultrasound Addiction Therapy for Pregnant Women or other routine services.” When State Sen. Dick Harpootlian, D-Richland, heard that women in South Carolina are shackled in childbirth, he said, “I think this is a shock that we continue to still shackle pregnant women”.

This is us. We cannot be shocked or surprised at the shackling of women in childbirth. In both Florida and South Carolina, dignity is invoked, specifically dignity for incarcerated women. Think of how far we have fallen that not shackling women in childbirth is considered dignity. I hope that both Florida and South Carolina do pass their respective bills into law, and I hope that we will work for a better understanding of dignity.

(Image Credit 1: Radical Doula) (Image Credit 2: New York Times / Andrea Dezsö)