Since 1973, Canada has run the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, or TFWP. Initially designed to bring in `high-skilled’ and specialized workers, in 2002 it was revised in order to bring in “low-skilled” workers who now make up the overwhelming majority of TFWP workers. Eight years ago, two Mexican sisters took on the injustice of the TFWP and, last week, won a landmark victory for women workers everywhere.

In August 2007, two sisters, now known as O.P.T. and M.P.T., left Mexico to work in Canada under the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. They were employed by Presteve Foods Ltd, in Ontario, owned at the time by Jose Pratás. At the time Pratás was 74. O.P.T. is now 36 years old, and her sister is 30.

According to both sisters, Pratás immediately started making explicit sexual advances towards O.P.T. and then demanded sex. Whenever O.P.T offered resistance, Pratás would threaten to send her back to Mexico. This was no idle threat. Under the TFWP, “temporary workers” are attached to their employers. In the Spring of 2008, O.P.T. fled Presteve, moved to Windsor for a bit, and then returned to Mexico.

In the Spring of 2009, the CAW-Canada union, now called Unifor, filed a brief with the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, on behalf of 39 Thai and Mexican women workers employed at Presteve. Then things moved both quickly and slowly. Pratás was charged with 23 criminal charges of sexual assault and five counts of common assault, all involving women “temporary foreign workers”. In March 2010, Pratás pleaded guilty to one count of assault, and received a conditional sentence and some probation.

Ultimately, of the original 39 claimants, only O.P.T. and M.P.T. were left to challenge the power of Presteve Foods, Jose Pratás and the entire Temporary Food Works Program.

Last Wednesday, the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario handed down its decision and awarded O.P.T. a record $165,000 as compensation for “injury to her dignity, feelings and self-respect”. The Tribunal also awarded M.P.T. $55,000. Pratás and Presteve Foods, now owned by Pratás’s son, must pay the two sisters $220,000 for having created a “sexually poisoned work environment”.

After the hearing, O.P.T. said, “I want to tell all women that are in a similar situation, that they should not be silent and that there is justice and they should not just accept mistreatment or humiliation. We must not stay silent. [As a migrant] one feels that she or he has to stay there [in the workplace] and there is nowhere to go or no one to talk to. Under the temporary foreign worker program, the boss has all the power – over your money, house, status, everything. They have you tied to their will. It has been 8 years to obtain justice but 8 years and justice is finally here today.

“If we don’t do what they say, they have the power to deport. We are obligated to work. Not as people, but as slaves. We endure wage theft, verbal abuse, physical abuse, and our bodies are injured because of the stress of the work. They push and push us. How can you say that we are free when in practice we have no right to leave?

“But how can we leave, if we cannot work for another employer. They harm us, and then they send us home. There is racism underlying their treatment of us. How is this allowed in Canada? That happened to me eight years ago, and the system is still the same. Treat us with dignity. Not as animals. But as human beings who merit respect.

“Even when we have been humiliated and mistreated, we have to hang on to our dignity. That is all we have.”

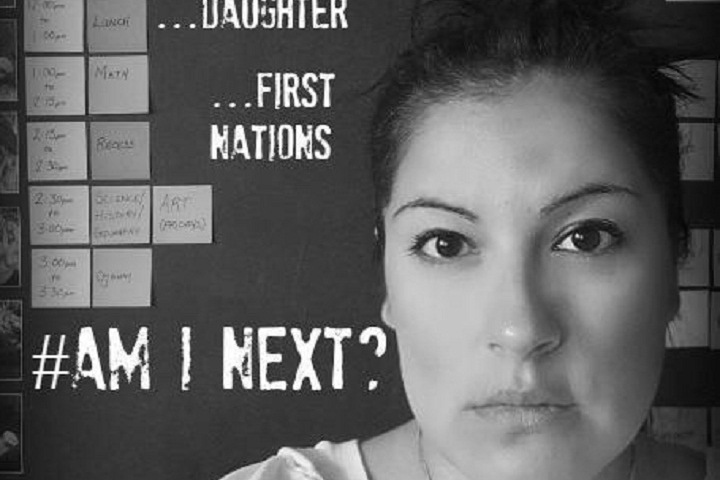

Canada created a system in which workers were tied, handcuffed, to their employers, in which workers were forced into almost complete dependence on employers. Employers then sought women workers, whom, by law, they are allowed to pay less for the same work as male workers in the program. Women in the caregivers’ program suffer the same violence.

O.P.T’s and M.P.T.’s victory is a victory for women workers across Canada and around the world, as they struggle with the violence of `national economic growth.’ We have to hang on to our dignity. That is all we have.

(Photo Credit: thestar.com)