The State of Florida, the so-called Sunshine State, has a drug problem, a drug crisis actually. The State seems hooked on psychotropic drugs for children. And not just any children. The most vulnerable children. Foster children. Children in prison. Children in various forms and modes of `custody’.

Two years ago, on April 16, 2009, Gabriel Myers, a seven-year-old child, hanged himself. Gabriel was in foster care. At the time of his death, Gabriel was prescribed psychotropic medications. The State of Florida Department of Children and Families appointed a work group, the Gabriel Myers Work Group, to look into both the circumstances of Gabriel’s death, and life, and that of all children in State foster care.

Gabriel was placed in foster care in order to take him out of a traumatically abusive household. He was “brought into care June 29, 2008.” Ten months later, he was dead. It happens that quickly, and it happened that torturously slowly as well. Gabriel saw psychiatrists and therapists. He was described as “overwhelmed with change and possibly re-experiencing trauma.” He engaged in self-destructive behavior.

The Work Group found that, while there were many caring adults around Gabriel, in the end he was “no one’s child.” No one adult took full responsibility, and so there was no one to notice or address failures, gaps, and lapses in treatment. For example, there was no one to ask hard, even belligerent, questions about the effects and impact of psychotropic drugs on a child. According to the Work Group, there was no sense of urgency: “Because the perception of time for a child is compressed, a demonstrated sense of urgency by adults is vital.”

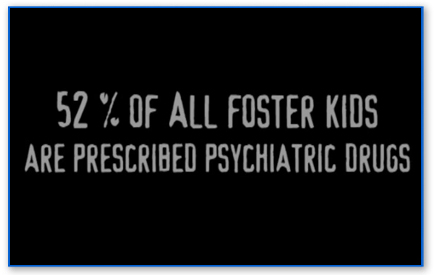

The Work Group found that, while nationally 5% of all children receive psychotropic medication, among Florida’s foster kids, the rate was 15.2%. Florida has all sorts of protocols and regulations, but if there’s no one, no adult, with a vital and demonstrated sense of urgency, the drugs flow. Gabriel’s tragedy was one of repeatedly missed opportunities for real treatment, for real help, for real care. That was the Report of the Gabriel Myers Work Group, November 19, 2009.

That was two years ago. And today?

Today, Florida distributes psychotropic drugs, with what amounts to abandon, to children in prison. Doctors are prescribing psychotropic drugs more often than ibuprofen. In 2007, according to a report last week, the Department of Juvenile Justice bought more than twice as much Seroquel as ibuprofen for its state-operated jails and homes for children.

Again, there’s little or no oversight. By its own admission, the State doesn’t know where most of the drugs are. This is called a “functionality” concern. There’s little or no oversight, as well, concerning conflict of interest between prescribing doctors and the pharmaceutical corporations.

What’s going on in Florida? According to Broward County Public Defender Howard Finkelstein, whose office represents children in juvenile court, it’s battery: “If kids are being given these drugs without proper diagnosis, and it is being used as a ‘chemical restraint,’ I would characterize it as a crime. A battery – a battery of the brain each and every time it is given.”

According to Dr. Glenn Currier, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Rochester in New York, the doses are extraordinarily high. When asked about a case involving one young female prisoner, Dr. Currier remarked: “I have heard of doses that high in large adult males. But not in girls.”

Florida used to put juveniles in prison for life, without any chance of parole, for non-homicide offenses. Last year, in Graham v Florida, the US Supreme Court ruled that it could no longer do so. In the 1990s, Florida sent 7000 children to adult courts. That’s more than the rest of the country, combined.

What’s going on in Florida is a crisis, a crisis of care, a crisis of urgency. The State is distributing deadly drugs to its most vulnerable children. And that’s a crime.

(Image credit: CCHR International)