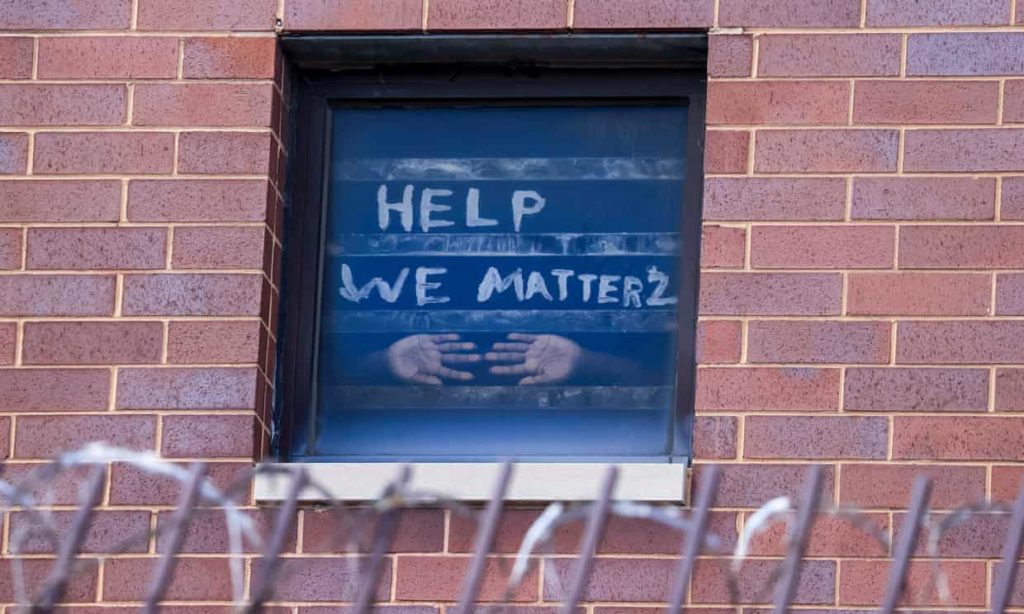

On Wednesday, May 17, Anadith Tanay Reyes Alvarez, an eight-year-old girl born in Panama to Honduran parents, died while in U.S. border custody. She had been detained for a week — more than twice the amount of time the government generally aims to hold migrants, particularly children. On Wednesday, May 10, Ángel Eduardo Maradiaga Espinoza, a 17-year-old Honduran boy died in U.S. border custody. Here’s how these tragedies were described: “In the past week the authorities have struggled with overcrowding at border facilities.” “In recent weeks the U.S. has struggled with large numbers of migrants coming to the border.” Authorities have struggled? The U.S. has struggled? What about Alvarez’s parents, who now call for justice, who now struggle to remind the world, “My daughter is a human being, they had to take care of her”. What about Espinoza’s mother, Norma Saraí Espinoza Maradiaga, who struggles to get answers, “I want to clear up my son’s real cause of death. No one tells me anything. The anguish is killing me. They say they are awaiting the autopsy results and don’t give me any other answer.” Stories matter. How stories are told matters. Nation-states with overcrowded prisons, jails, juvenile detention centers, immigrant detention centers do not `struggle’ with the overcrowding. If they did, they would do more than take timid steps to `address overcrowding’. They would end the everywhere-to-prison pipelines that crisscross the globe. Consider the last month of overcrowding, in no special order, as an example. And here, though obvious, it must be said these reports are only from places that actually allow any sorts of reporting.

In London, Ontario, the province settled a $33 million lawsuit concerning the conditions in London’s Elgin Middlesex Detention Centre, built for a maximum of 150 people, often holding as many as 500.

In the Indian state of Bihar, 59 jails, including eight central prisons, are built for a maximum of 47,750 people. Currently, they hold 61,891 people, described as “languishing” while the state “struggles with overcrowding”. Meanwhile, the Amphalla jail, in Jammu, “against a holding capacity of 426 prisoners has more than 700 inmates”.

Cyprus’s prisons, with a maximum capacity of 100, hold 146 people, making it the most overcrowded prison in Europe. After Cyprus, in descending order, come Romania, France, Greece, Italy, Sweden, Croatia, Denmark. French prisons are designed to house at most 60,899 people. As of April 1, they housed 73,080. At 120% of capacity, that’s “an all-time record”.

In late April, in Ireland, the Dóchas Centre, built to hold no more than 105 women, housed 170 women – 162% of its original capacity. Remember the 2021 Chaplains Report on the Dóchas Centre “being used as a dumping ground”? Two years later, the state is still `struggling’.

The UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture visited Madagascar prisons, for the first time, and found many were “close 1000% …. With half of its prison population in pre-trial detention, Madagascar should reconsider its criminal policies and enact urgent measures, including alternatives to imprisonment, to reduce this grave level of overcrowding that constitutes cruel, inhuman and degrading conditions of detention, contrary to international law standards.”

On Friday, May 19, Zimbabwe started releasing 4000 incarcerated people. Why? With a capacity of 17,000, Zimbabwe’s prisons house over 20,000 people. Uganda was `shocked’ to learn, this week, that its prisons, with a maximum capacity of 20,036 people, currently holds 74,444 people, or an occupancy rate of 371.6%: “With the rising numbers, prison authorities are struggling to feed their daily average of 81,729 prisoners”. Authorities are struggling, incarcerated people are starving.

Kenya’s prisons at more than 200% capacity. As elsewhere, as pretty much everywhere, there aren’t enough beds to go around. People are sleeping on the floor. The answer? A new campaign: “One prisoner, one bed, one mattress”. Interior Principal Secretary in the State Department for Correctional Services Mary Muthoni is looking to acquire 60,000 mattresses and beds to address the floor sleeping crisis. This is how the state `struggles’. Meanwhile, more than 10,000 incarcerated people are serving sentences of less than three years, and 41% of the prison population are bailable remand incarcerated people. They are people who have not been tried but cannot afford bail. In Nigeria, where 82 correctional centers are over capacity, 80% of those incarcerated are awaiting trial.

When an eight-year-old girl or a 17-year-old boy dies in an overcrowded detention center; when hundreds of thousands of people are starving in overcrowded prisons and jails; when hundreds of thousands of people are sleeping on the bare floor; when millions are locked down for days; the story is not that the state is struggling. The story is torture. End torture now. Stop sending people to prisons, jails, juvenile detention centers, immigrant detention centers.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: The Guardian / Tannen Maury / EPA)