On May 19th, Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas stood before an audience gathered for the Hudson Institute’s event on Crime and Justice in America and argued that the United States of America is currently suffering from an under-incarceration problem. Yes, Senator Cotton believes that the country with 25% of the world’s prison population has an under-incarceration problem.

The gist of Senator Cotton’s argument, and overly simplified linear logic, is how could we have a mass incarceration problem when so many “criminals” are getting away. Well, Senator Cotton, allow me to explain. The problem with mass incarceration is not simply how many people we have incarcerated (though that is a big part of it) but who this country is incarcerating by the millions. The simple answer is low-income men and women of color for predominately low-level drug offenses.

To better understand the fallacy of the ‘Gentleman’ from Arkansas’ logic, we can turn to the fastest growing prison population: women. Since the introduction of federal and state level policies like broken-window policing, 3-strike laws, mandatory minimums (policies Cotton credits with turning around our society), the number of women in prison has risen 700%. Of the 215, 332 women who have entered prison, nearly half have entered for drug-related offenses. In the world Tom Cotton lives in, a longer prison sentence will help these women beat drug addiction and rehabilitate them into law-abiding citizens. In reality, these women will sit in prisons where only 10% will receive any form of substance abuse treatment. For those that do receive treatment, the treatment they receive is based on the substance abuse history of men and has been found to be largely ineffective.

Prisons do not just serve as makeshift substance abuse treatment centers, in which the majority of incarcerated women have substance abuse histories and barely any women actually receive substance abuse treatment. Prisons also serve as mismanaged, ill-equipped, and overcrowded places to house women with mental health concerns. While 12% of women in the general population have mental health concerns, 73% of women in state prisons, 61% of women in federal prisons, and 75% of women in jails have mental health disorders. Again, these women are largely low-income women of color. For these women, “treatment” often comes in the form of restrictive housing (solitary confinement), a form of punishment that has been shown to cause psychotic episodes, hallucinations, and suicidal tendencies.

Cotton also gives credit to the “thankless” work of Correction Officers who work tirelessly to rehabilitate individuals in prison and keep them safe. In reality, women are perhaps in more danger inside cell walls. Kim Shayo Buchanan describes prisons as if “the clock has been turned back to the nineteenth century. Women, especially women of color, are exposed to institutionalized sexual abuse, while a network of legal rules prevents them from seeking protection or redress in courts. Guards know they can sexually exploit women without fear of institutional sanction or civil liability”. Despite making up only 10% of the prison population, women make up nearly half of all survivors of sexual assault in American prisons.

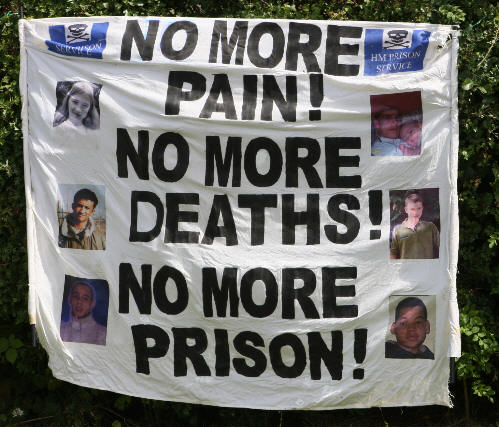

Senator Cotton, the prisons you imagine, places where bad people go to repent for their wrong doings, do not exist. The US penal system currently operates as a place to control, abuse, and neglect our nation’s poor and mentally ill. The answer to the issues Senator Cotton worries about is not an increase of punishment but an increase in attention and investment to the communities that are being effected by our MASS incarceration.

(Image Credit: Bitch Media) (Photo Credit: LA Progressive / Lea Suzuki / The Chronicle)