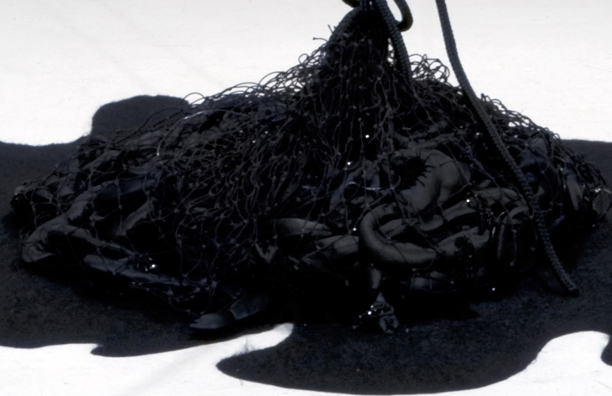

Deepwater Dirge by Dana Sherwood

April 20, 2011. It is a year to the day since the Deepwater Horizon rig exploded, sending fire into the sky, oil into the seas, and death and destruction across space and time. It is a year since eleven workers were killed, some say murdered, by the `inevitable’ conditions of work on that rig.

Eleven workers died that day: Jason Anderson, Aaron Dale Burkeen, Donald Clark, Stephen Curtis, Gordon Jones, Roy Wyatt Kemp, Karl Dale Kleppinger, Blair Manuel, Dewey Revette, Shane Roshto, Adam Wiese.

Nine women became widows that day: Shelly Anderson, Rhonda Burkeen, Sheila Clark, Nancy Curtis, Michelle Jones, Courtney Kemp, Tracy Kleppinger, Sherri Revette, Natalie Roshto. For a year, these women have mourned and grieved and organized. They continue to mourn, grieve, organize. They continue to take care of their daughters and sons and lives. The work of mourning and the work of survival are one. But for these women, and their children, and their loved ones and neighbors and communities, the work of memory has become critical.

And the work of memory is difficult, arduous even. Theresa Carpenter, Courtney Kemp’s mother, knows the men’s names are vanishing from the public conscience: “These men are all but forgotten except by their families.” Billy Anderson, Jason Anderson’s father, knows as well: “”Within seven or 10 days as far as the media’s concerned, those guys didn’t count for anything. They cared more about some oil-covered pelican or little bird, or something. It was like those 11 men’s lives didn’t mean anything.”

What is the meaning of these workers’ lives? What is the meaning of mourning? What is the meaning of grief? What is the meaning of memory? A year ago the sky blew up and the waters seized. Today, according to many, the situation is the same. Ask the fisher folk, like Diane Wilson or Darla Rooks or Kim Chauvin or Rosina Philippe and her aunt Geraldine Philippe.

What is the meaning of memory if we continue to insist on forgetting? Twenty years ago, in 1991, Adrienne Rich’s collection, An Atlas of the Difficult World was published. The title poem, “An Atlas of the Difficult World”, has thirteen sections. The second section is entitled, “Here is a map of our country.”

“Here is a map of our country:

here is the Sea of Indifference, glazed with salt

This is the haunted river flowing from brow to groin

we dare not taste its water . . . .

This is the sea-town of myth and story when the fishing fleets

went bankrupt here is where the jobs were on the pier

processing frozen fishsticks hourly wages and no shares ….”

Here is a map of our country, twenty years ago, one year ago, today … and tomorrow? The Gulf of Mexico is a natural body of water. We, however, are the builders of the Gulf of Mourning and Memory. A year later the situation is still the same.

(Image Credit: Dana Sherwood http://danasherwoodstudio.com/projects/deepwater-dirge-2011)