On Tuesday, May 30, 2023, Argentina’s Minister of Health, Carla Vizzotti, issued Resolution 1062/2023, concerning access to emergency contraception. As of Wednesday, the so-called morning after pill became available over the counter, without a prescription. This major step forward resulted from decades of intense organizing by women’s groups, feminists, and allies. While much of the United States threatens the rights, autonomy, well-being, and safety of women and girls, Argentina leads the world in a better, safer, and more just direction.

After some preliminary considerations, the Resolution states, “That the right to access contraception in all its forms is part of sexual and reproductive rights, recognized as basic human rights enshrined in human rights treaties that have constitutional status. Likewise, the State has committed itself to the reduction of unintended pregnancies, in successive platforms since the signing of the Program of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (CIPD, 1994) in which it was recognized that empowerment, full equality and empowerment of women were essential for social and economic progress. To this end, it has committed to promoting the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development, which explicitly recognizes the key role of sexual and reproductive health and gender equality and establishes goals linked to the capacity of women, adolescents and all people with the ability to gestate to make informed decisions about sexual relations, timely access to the use of contraceptives and comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care.”

The Resolution concludes, “Every person of childbearing age must have timely access and without regulatory restrictions to emergency hormonal contraception (AHE), knowing that this is the last chance for contraception after sexual intercourse and thereby reducing maternal mortality and morbidity caused by unsafe abortions.”

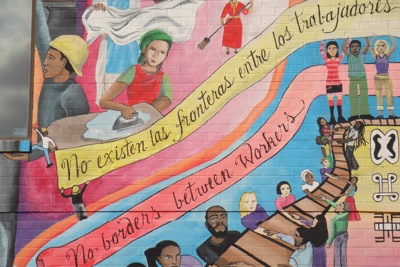

Every person of childbearing age. Not only those who can afford to travel somewhere else. Not only those who are connected to various networks, of class or ethne/race or other affiliation. Every person of childbearing age. This is part of sexual and reproductive rights, recognized as basic human rights.

In Argentina, women’s and feminist movements have been organizing around just this point since at least the 1970s. In 1973, for example, a flyer created and distributed by la Unión Feminista Argentina, UFA, proclaimed: ““El embarazo no deseado es un modo de esclavitud / Basta de abortos clandestinos / Por la legalidad del aborto / Feminismo en marcha”. “”Unwanted pregnancy is a form of slavery / Enough of clandestine abortions / For the legality of abortion / Feminism on the march”. Fifty years later, almost to the day, that march is still ongoing, intensifying, expanding, succeeding.

In 2018, the lower legislative house, la Cámara de los Diputados, after long and intensive debate, voted to decriminalize abortion. The Senate rejected the bill. Undeterred, women’s groups, feminist movements and allies persisted. In the waning days of 2020, both houses of the legislature legalized abortion, which was signed into law January 14, 2021. Two years later, the organizing continues. The struggle for sexual and reproductive rights, understood and enforced as integral to human and civil rights, continues.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: Nursing Clio)