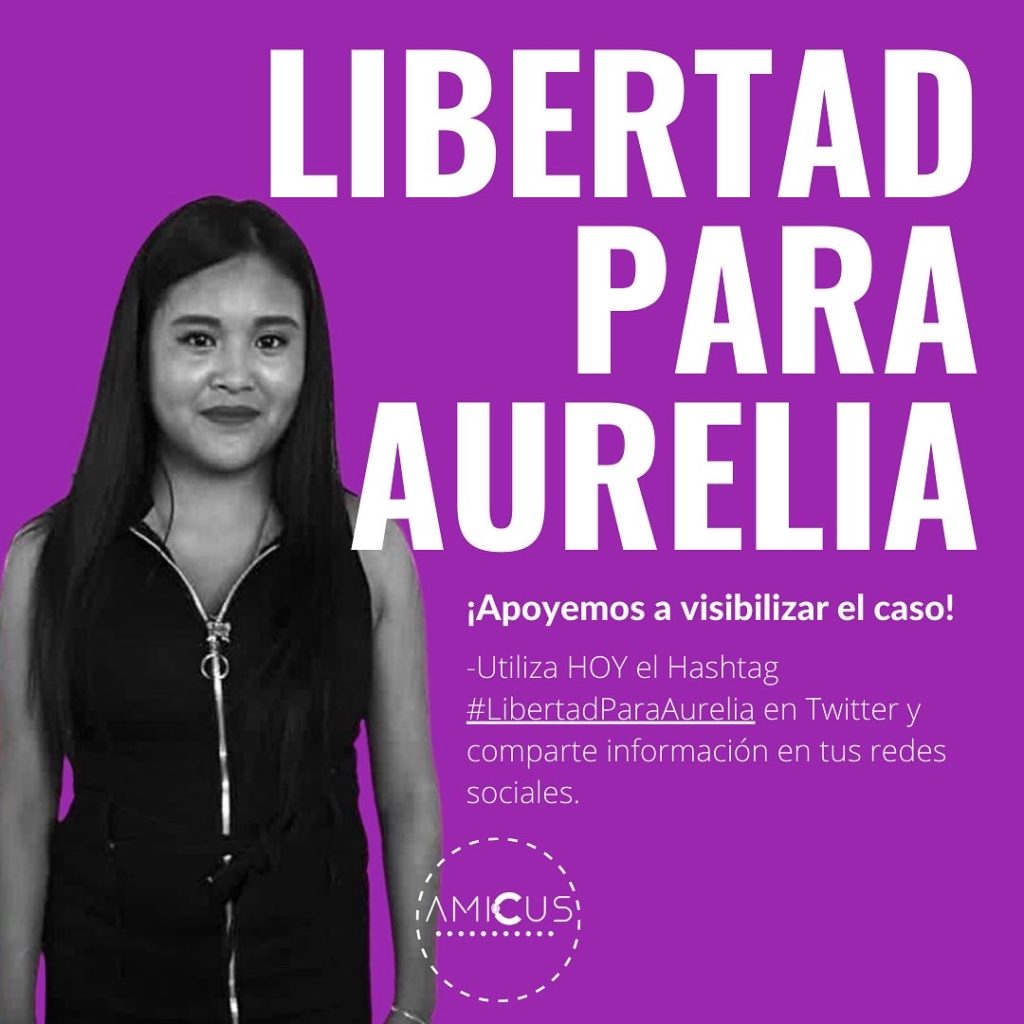

Last Tuesday, December 20, Aurelia García Cruceño walked out of, or was released from, Centro de Readaptación Social de Iguala, the local jail in Iguala, in Guerrero, in southwestern Mexico. She never should have been in prison in the first place. In 2019, Aurelia García suffered a miscarriage and was arrested for having had an abortion. Today, Aurelia García is 23. She spent the last three years in jail, in a state that decriminalized abortion in May 2022, in a country whose Supreme Court unanimously declared penalizing abortion as unconstitutional. And yet …

In 2019, Aurelia García Cruceño, a 19-year-old Náhua woman, lived in the town of Xochicalco, in the Chilapa de Álvarez Municipality, in the state of Guerrero. A town leader raped Aurelia García, who, because of the man’s stature in the community, felt she couldn’t accuse him, at least not successfully and not without further endangering herself. And so, in June 2019 she fled to her aunt’s house, in Iguala. Aurelia García had no idea that she was pregnant. She also spoke no Spanish.

Four months later, on October 2, 2019, Aurelia García began suffering intense pain and bleeding. Finally, after a week, she endured a miscarriage, an “involuntary abortion”. Her aunt walked in, saw Aurelia García lying, passed out, on the bed, covered in blood, and called the ambulance, who took her to the hospital. When Aurelia García awoke, she was handcuffed to the bed. She was then charged with homicide, tried, convicted, sentenced, imprisoned.

Again, Aurelia García Cruceño was 19 years old at the time and spoke no Spanish. The lawyers assigned to defend her spoke to her in Spanish, without any Náhuatl speaking translator present. The attorneys told her to plead guilty and take a 13-year sentence. Otherwise, they explained, she’d be imprisoned for 50 years. Aurelia García agreed and signed papers. She had no idea what she was agreeing to nor understood the papers she signed.

At no time was a Náhuatl speaking translator provided, not in the hospital, not by the police, not by her attorneys, not by the Court. And yet …

Feminist and human rights attorneys, organizations and activists jumped to Aurelia García’s defense, once they heard of the case. They brought Aurelia García’s case to court for five separate hearings, and finally arrived at something like justice, or at least the beginnings thereof.

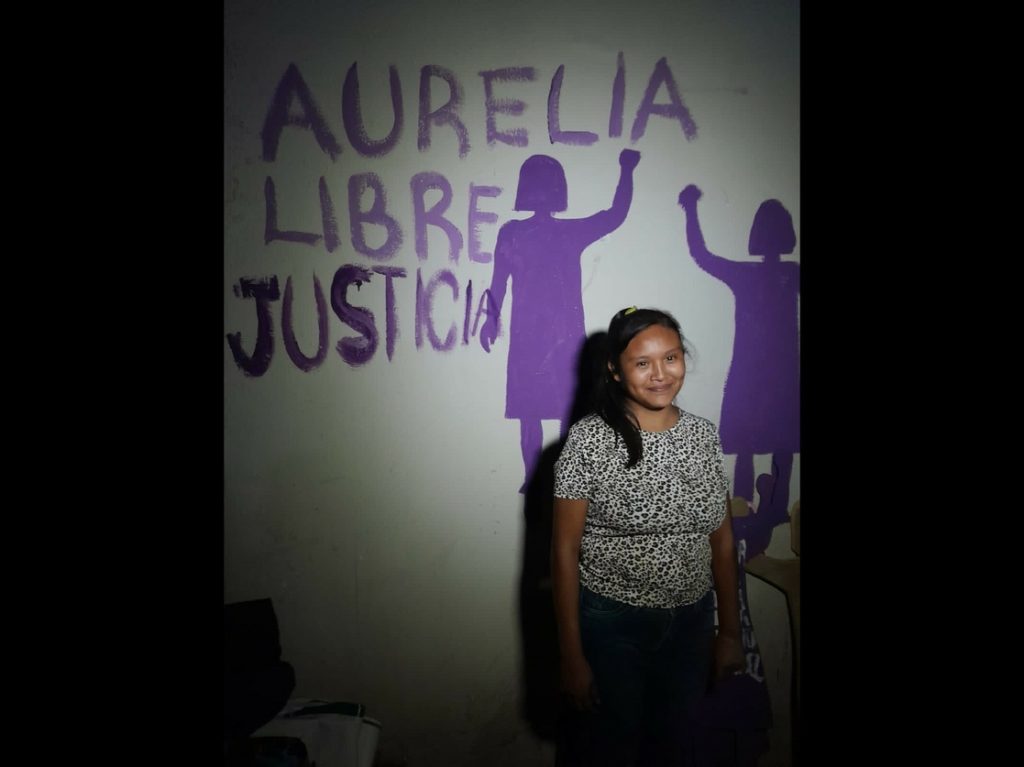

When Aurelia García walked out of prison, she was accompanied by her parents, Agustina Cruceño Naranjas and Alberto García Palazin, and her defense attorneys Verónica Garzón Bonetti and Ximena Ugarte Trangay. Aurelia García, who learned to speak Spanish while in prison, smiled and said, “I made myself strong to be able to move forward and beyond … I am going to study hard and hopefully I will achieve my dream of becoming a teacher … And I want to make sure that what happened to me never happens to anyone else. We cannot stay silent; we must talk and tell what is being done to us.”

Aurelia García Cruceño should never have been in prison. Her abuse by the State is an assault on women generally, on young women, on Indigenous women, on working poor women. As Aurelia García and her allies have noted, she was not alone in Iguala’s Center for Social Readaptation, far from it. In fact, the court has yet to hear the case of Maira Onofre Gómez, held in the same prison for exactly the same `crime’. How many more women must suffer this form of injustice, in Mexico and beyond? For now, Aurelia García Cruceño is with her family and supporters, waiting and preparing for the next trial, where she is suing the State for damages, and preparing for her future life, her dream, of becoming a bilingual teacher for Náhuatl-speaking indigenous children. May that kind of justice prevail.

Aurelia García Cruceño

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: Amicus / Twitter) (Photo Credit: La Jornada)