Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: first as tragedy, then as farce.

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

According to a report, “The transport of regional and remote prisoners”, released Monday, April 3, by the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services of Western Australia, history repeated itself recently. The report describes “Anna’s journey”, a “transport welfare fail”. It then notes that the exact same failure happened to another incarcerated woman … two weeks earlier. The report opens, “This review was prompted by a few recent incidents that raised questions for us about the conditions under which prisoners were being transported across regional Western Australia. It was also undertaken against a historical backdrop of the tragic case of Mr Ward who died during a prisoner transport in 2008. We set out to seek assurance that the gains made since 2008 have been sustained.” The report ends, “There is a clear gap in the monitoring of … movement services at regional locations, which should be addressed by the Department. This aligns with the findings of the Coroner following the death of Mr Ward, and a recommendation for the Department to conduct regular reviews of transport contractor services in regional locations (Hope, 2009).” What does it mean that a failure in 2022, reported in 2023, “aligns” with findings and recommendations, issued in 2009, concerning an incident in 2008?

In 2022, Anna entered Greenough Regional Prison, for the third time. The staff at Greenough knew Anna. Flagged as living with schizophrenia, Anna was known to have an extensive psychiatric history, including frequent episodes of self-harm and suicidal behavior. This time, in her first week or so, Anna was reported twice for uncooperative and erratic behavior. She stopped taking her medications. Despite her non-compliant and erratic behavior, it was decided to move Anna to Bandyup Women’s Prison. The pre-transfer report described Anna as “satisfactory – no major concerns”. When staff tried to place Anna on a plane headed for Bandyup, Anna urinated on herself in the transport vehicle and refused to wear a mask. The trip was cancelled. As Anna was being returned to Greenough, staff issued a new plan, with no mention of schizophrenia or any other issues. The new plan was to transport Anna by van the 400 some kilometers to Bandyup.

A week later, Anna was bundled, shackled and handcuffed, into the security pod of an escort van, and off they went. The journey was 4 hours and 35 minutes. During that trip, early on, Anna, still handcuffed and shackled, urinated. There was no CCTV footage or cell phone call recordings. There was no documentation of anything out of the ordinary. Perhaps that’s because there was nothing out of the ordinary. Two hours in wet clothes, shackled and handcuffed in a so-called security pod. All in a day’s work … if the person is an Aboriginal woman.

Anna’s story ends in redundancy: “Prior to Anna’s transfer, another female prisoner departed Greenough in early April 2022 and urinated in the vehicle. Upon arrival to Bandyup, staff were made aware that this prisoner had urinated in the pod during the journey. Many of the issues we identified with Anna’s experience were also present in this earlier case …. It is concerning, and disappointing, that staff failed to learn from this earlier incident and implement measures, such as bringing a change of clothes or a towel, that would have helped protect the dignity and welfare of Anna during her journey a few weeks later.”

It is concerning and disappointing, and altogether predictable. Staff did not fail to learn, they did not even have to refuse to learn, because there has been no reason to. Throughout the report, the Inspector invokes the tragic case of Mr. Ward, who died in a prisoner transport in Western Australia. In January 2008, Mr. Ward, 46 years old, a respected elder, was taken on a 220 mile ride across the blistering Central Desert to face a drunk driving charge. Mr. Ward had represented the Ngaanyatjarra lands across Australia and at international fora. The people who drove Mr. Ward threw him into the back of a Mazda van, into the security “pod” with metal seating and no air conditioning. All male remand prisoners are considered dangerous, or “high risk”. That Mr. Ward was known to be cooperative and congenial was irrelevant. For his own safety and welfare, he had to go in the back. The trip took almost four hours. The temperatures that day were 40 degrees Celsius, 104 degrees Fahrenheit. Mr. Ward died of heatstroke. He died with third degree burns. Mr. Ward cooked to death, slowly and in excruciating pain.

In a 2001 government study, identical Mazda `pods’ were described as “not fit for humans to be transported in.” They were seen as “a death waiting to happen.” In the intervening decade, there were other major reports, two in 2005, in 2006. In 2008, Mr. Ward was dumped into the oven of the back of that Mazda. When asked about the implications of Mr. Ward’s story, Keith Hamburger, the principal author of the 2005 report, responded, “That’s a matter of great concern because this is not rocket science, we’re dealing here with duty of care.”

A duty of care. In 2022, that duty of care meant two Aboriginal women, separately, abused. The list of Aboriginal women who died in custody, in Western Australia alone, is long: Maureen Mandijarra, 2012; Ms. Dhu, 2014; Cherdeena Wynne, 2019; JC, 2019. Many die in police custody, others in prisoner transport vans, others in their cells. Year after year, the Inspector of Custodial Services for Western Australia has described Anna’s ultimate destination, Bandyup Women’s Prison, the only women’s prison in Western Australia, as a hellhole. Speaking of Bandyup, the Inspector said, “I wanted to know how such an event could occur in a 21st Century Australian prison and to prevent it happening again.” First as tragedy, then as farce does not mean the second time is funny. For those forced to suffer, the pain is new, and yet not new, each time. The farce is in the expressions of surprise, discovery, concern of the perpetrators. It is concerning and disappointing … and happening somewhere right now.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

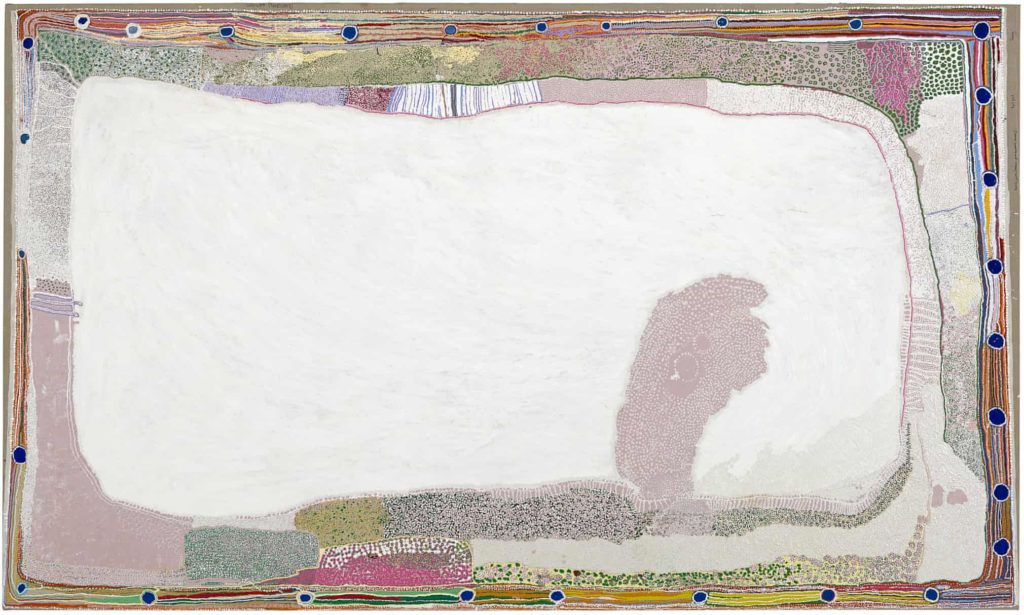

(Image Credit: Ngayarta Kujarra by Jakayu Biljabu, Yikartu Bumba, May Chapman, Nyanjilpayi Nancy Chapman, Doreen Chapman, Linda James, Donna Loxton, Mulyatingki Marney, Reena Rogers, Beatrice Simpson, Ronelle Simpson, and Muntararr Rosie Williams / The National Gallery of Victoria)