“Yearning is the word that best describes a common psychological state shared by many of us, cutting across boundaries of race, class, gender, and sexual practice. Specifically, in relation to the post-modernist deconstruction of ‘master’ narratives, the yearning that wells in the hearts and minds of those whom such narratives have silenced is the longing for critical voice”.

bell hooks. Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (1990)

On December 6, 2021, the 32nd anniversary of the massacre of women students at the École Polytechnique de Montréal, as every day, artists around the world struggle against State violence to seek, find, create freedom, justice, peace, documentation, voice, reflection, memory, mourning, meaning and more. In eSwatini, artists struggle with erasure, locally and globally. In Sudan, both during and after the coup, if this is indeed after the coup, artists struggle with threats to freedom as well as to their own lives. In Belarus, artists struggle with imprisonment and persecution. In the United States, artists struggle with racist and racialized violence. In all four locations, and beyond and between, artists struggle to create democratic spaces that will themselves generate networks of democratic practice and shared yearning.

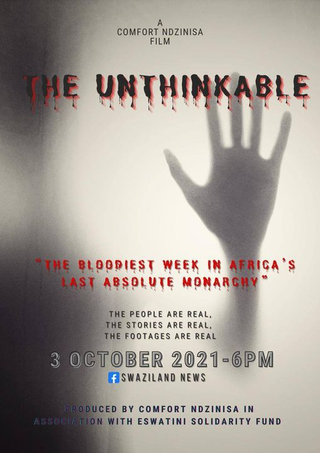

June and July 2021 saw mass protests across eSwatini and saw as well … very little. That is, while the State responded with intense police brutality, in some cases hitherto unknown forms of torture, the world looked elsewhere. Artists refused to accept the violence, the silencing by the national government, and the lack of concern of the global polity. As the protests and State violence erupted, local activists pulled out their phones and began filming. Then they consolidated their energies and resources into the eSwatini Solidarity Fund, and ultimately produced the documentary film, The Unthinkable. As university student and Fund volunteer Tibusiso Mdluli noted, “Our struggles have been sort of erased. I get the sense that people in the international community do not know so much about Swaziland.” With showings already held in the United States, Norway, Taiwan and South Africa, plus a broadcast on South African television, and more in the works, hopefully the erasure is beginning to dissipate.

In October, the military of Sudan conducted a coup, removing the Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, and installing themselves, of course, in his stead. About a month later, after intense, daily, mass protests, Prime Minister Hamdok was `released’ and `reinstated’ … sort of … maybe. Artists refused to stand down after the coup and during the military regime and have refused to accept anything but a full removal of the military from the Executive branch of government and a clear and verifiable movement forward towards democracy. As Aamira explained, “We artists will be the first to be targeted if the military government continues in power. We are demonstrating in the streets, facing guns, unarmed. There is nothing to fear any more.”

During the reign of Alexander Lukashenko, life for artists and pretty much everyone in Belarus has been difficult and always under threat. In that environment, Natalia Kaliada and Nikolai Khalezin founded the Belarus Free Theatre, sixteen years ago. For that act of courage, Kaliada and Khalezin were forced into exile ten years ago. This year, the rest of the company has decided, or been forced to decide, to follow suit. Nevertheless, they persist in creating dramatic and existential spaces, which they stream into their native country, in which Belarussians can dream of and aspire to democracy and freedom. As Natalia Kaliada explained, “We know we are stronger than the regime. The authorities are more scared of artists than of political statements. Everyone believes that things will change in Belarus, but for now the company needs to be safe. We ask the UK public to stand in solidarity with us at this most critical time in our history. Solidarity is crucial for our survival.” The struggle for democracy and freedom needs solidarity more than martyrs.

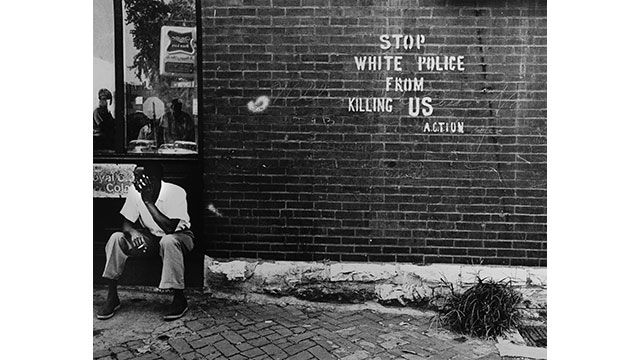

In the United States, over the past century, American artists have struggled with anti-Black violence, by the State directly or informally but firmly authorized by the State. Next month, in Chicago, an exhibition entitled “A Site of Struggle: American Art Against Anti-Black Violence” will open. The exhibition will begin with works from the anti-lynching campaigns of the 1890s and conclude with the founding of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013. The organizers of this exhibition began working on it in 2016, in the aftermath of national protests, including those involving the deaths of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Akai Gurley, Tamir Rice, in 2014; Freddie Gray and Sandra Bland, in 2015, as well as the massacre at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, in Charleston, South Carolina, to name but a few; and in the midst of ongoing demonstrations that year involving the deaths of Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Korryn Gaines, again to name but a few. Five years later, the exhibition is ready. According to its curator, Janet Dees, “‘A Site of Struggle’ employs art history to help inform our understanding of the deep roots of racial violence. From realism to abstraction, from direct to more subtle approaches, American artists have developed a century of tools and creative strategies to stand against enduring images of African American suffering and death. Contemporary artists taking on this subject are doing so within a long and rich history of American art and visual culture that has sought to contend with the realities of anti-Black violence.”

These four examples – artists from and of eSwatini, Sudan, Belarus, and the United States – were all reported on today. They all swim in long histories of local and global artistic refusal and resistance as well as confirmation and yearning. They all make the river by swimming and, in so doing, sustain our longing for critical voice.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit 1: New Frame) (Photo Credit 2: Darryl Cowherd / Museum of Contemporary Photography / Northwestern Now)