We are all drowning. We are all drowning while upholding a repressive system that can never provide freedom and justice for all women, a system in which a cycle of violence, suffering, and mass incarceration seems inevitable. We are Black women, arguably the most dehumanized and undervalued identity group. To be Black and also a woman places one in a position of endless performance and scrutiny. It’s tiring and so many cannot meet the standards that are set. Even when some of these benchmarks are met, expectations shift. We’re hunted and no matter what steps we take we are failures. So whom should we blame? Is it the lazy women who simply don’t have the capabilities to succeed, or the system that views them as unworthy, dehumanizes them, and resorts to violence to rid them of any thought of freedom?

The entire system is guilty. Capitalism is committed to the racism and sexism that demeans and imprisons Black women. Despite its violence, the system finds the most creative ways to justify its contradictions and injustices. Imagining a world where everyone recognizes this and strives to make amends is a real challenge. At this moment I feel deeply that there are generations of Black women who have never envisioned freedom. I know deeply that we have invested in a system that continues to fail us.

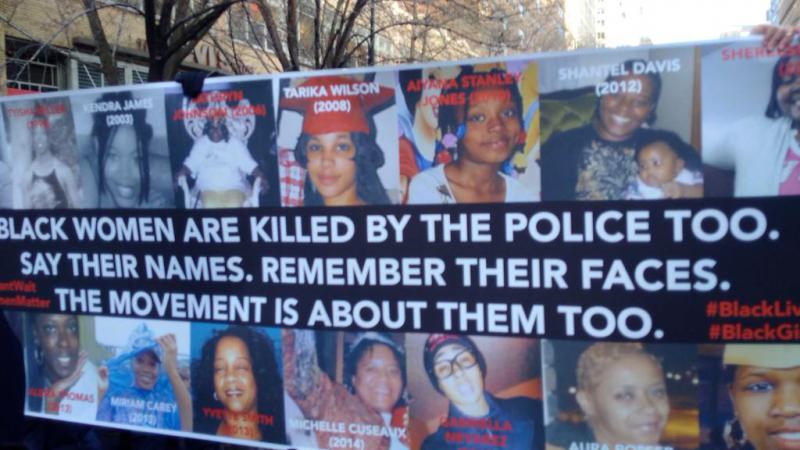

Since Trayvon Martin was murdered, there has been a slow awakening, or revitalization, of a younger generation that forgot the history of racial oppression that has always existed in this country. Their eyes opened, articles were shared, collective actions were planned, coalitions called for justice. But who is deserving of this justice? The #BlackLivesMatter movement was created by Black women and has progressed due to the efforts and outright fear and anger of Black women around the world. Yet, these women, Black women, are continuously erased from the narrative of state brutality. People of color become synonymous with men of color and the strength of the collective is weakened.

There can only be surface level reform if civil rights activists and everyday citizens feel compelled to protest and cry when Black men like Eric Gardner are brutally murdered by the state, but remain silent as women like Rekia Boyd and Natasha McKenna are tossed away. Why is it easier to mourn the loss of Black men than Black women? Are we convinced that when a woman experiences violence she brought it on herself or have Black women been so dehumanized that they are considered undeserving of justice, of freedom?

Last week, I attended an event in DuPont Circle, Washington, DC, entitled “Vigil for Rekia Boyd, Black Women, Trans Women, and Girls,” and then later in the evening attended a Justice for Freddie Gray march. The vigil in DuPont was amazing because it highlighted the plight of incarcerated and marginalized Black women within the civil rights narrative. There exists a narrative that asks Black women to choose their Blackness and align with Black men on every issue or choose their womanhood and go against Black men. That narrative is beyond trite. Black women are always both: Black and woman. Those identities cannot be separated and does not excuse a submission to patriarchal tendencies of Black male leaders. Together, in a space with women of color, everyone flourished. Voices that had been squashed spoke their truths and the need for continual spaces of mutual understand was highlighted.

So, we fight. Once we collect one golden moment and can begin to picture what collective freedom involves, we want more. The fight is not easy. Black women are hunted, disregarded, and divided. Does a single mother working a minimum wage job have the same time to envision freedom as a full-time student whose only real job is to consume knowledge? These are extremes but they must be considered when we speak about the collective and teaching empowerment. Some people live in fear that they have more to lose than others.

It’s all so heavy. What a burden, to be targeted, devalued, yet expected to perform to standards that are always shifting. So we drown, we come up for air momentarily, and then we sink again. Collective freedom will not come instantaneously. It’s a process that will take generations and generations but the goal is to break away from chains that have held us down for centuries. We deserve more than survival. We deserve freedom from capitalism, a system that divides us and perpetuates racism, sexism, and patriarchy. Regardless of status or educational level, Black women have been expelled from the dominant political economy and we must find new spaces of hope. We have been controlled by a violent empire and denied tenderness and understanding.

If more spaces for Black women open up in the #BlackLivesMatter movement, Black women may be able to create their own space and discover tenderness as freedom. Tenderness as currency. Tenderness as motivation to collaborate. Tenderness to bring about change. Tenderness that is hard and critical; tenderness that allows all us to inhale and find comfort in each other.

(Image Credit: Black Left Unity Blog blunblog.org)