“And she had learned from experience that Need was a warehouse that could accommodate a considerable amount of cruelty.”

Arundhati Roy, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness

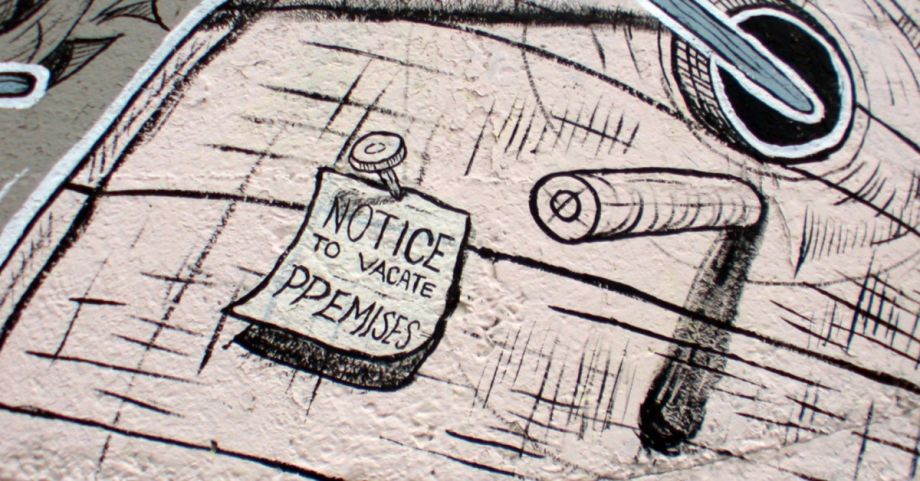

2025 began as 2024 ended, skyrocketing eviction filings, soaring evictions, mounting homelessness amid calls from many quarters to “address homelessness” by evicting the unhoused from their encampments, from their homes, however temporary, all in the name of some purported need. Consider two stories, one from the United Kingdom last year, one from Canada this year, days apart.

Jack is twelve years old and lives in Liverpool. His family was given a Section 21, or “no-fault”, eviction notice. The family was given two months to move, sixty days to find a place they could afford. There was no such place, and so they were moved into a hotel space, one room, two beds, a kettle. That’s it. As Jack explains, “It was just tiny, horrible, it wasn’t very suitable for children and all you could basically do was just watch TV or go to sleep. It’s just misery. … It was just like a game trying to get past a level, it was just day after day after day, a struggle.”

According to the housing organization Shelter, every day, day in day out, around 500 private rental households receive a Section 21 eviction notice. This year the number of so-called no-fault eviction filings broke all records. As one tenant explained, “I paid my rent every month, but I had no rights.” This is what “no fault” eviction means: no rights and misery, especially for children.

Across the ocean, in Hamilton, Canada, the new year began with this account: “Beverly Hoadley never thought she’d have to move out of her Hamilton apartment of over 50 years. But now facing a possible eviction, the 87-year-old says she’s afraid she’ll soon have no choice but to leave her beloved home. `It’s pretty awful,” Hoadley told CBC Hamilton a week before Christmas. `I’m not sleeping at night. It’s torture.’”

Beverly Hoadley and her now deceased husband moved into her apartment in 1970. At the time, the rent was $137 a month, for a one-bedroom apartment. Half a century later, she’s paying $820 a month. Although she’s on a fixed income, as are many residents in the building, she says it’s manageable. Or it was, until new owners, ironically named Endless Property Holdings, bought the building in September and promptly sent eviction notices to everyone, claiming they had to renovate the building. Tenants and allies are organizing to oppose the eviction. As one resident, also on fixed income, explained, “I feel terrible. I have nowhere to go.” The median rent for a one-bedroom in Hamilton is $1650 a month. While that’s a 3% decrease over the previous year, rents are rapidly rising once again. When people say they have nowhere to go, they have nowhere to go.

The landlord, Endless Property Holdings, say they need to renovate. The building has gone through recent renovations, the residents offered to accommodate any further renovations. The landlord rejected all claims and offers. Why is 12-year-old Jack subjected to misery, why is 87-year-old Beverly Hoadley subjected to torture? Landlord “need”. Year’s end, year’s beginning, children, elders, misery, torture. Need is a warehouse the accommodates a considerable amount of cruelty.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: John Bell, The Reward of Cruelty / Metropolitan Museum of Art)