I appreciate the Christian ethos of forgiveness. But in the most generally used and accepted meaning of the practice, the protocol of forgiveness requires that one come humbly, make confession of one’s sins, and ASK for forgiveness; and once asked for and penance received and acted upon, forgiveness is granted by God. So as appreciative as I am of this protocol, I am equally troubled by what appears to be our training to almost knee-jerk hand out forgiveness. This is something I worry that works against us, for it seems to demand we forgive but without our right to wholly engage our pain, our need to heal, our right to be restored–and then the time to actually do these things. One cannot dictate another’s healing or grieving process or timeline, and that’s not my attempt here. But I worry that if past is prologue, the way we’ve been trained to say ‘I forgive,’ absent, it appears, critical unpacking, moves the dialogue too fast and us into a supplicating position where we “forgive the sinner, hate the sin,” and then are forced to move forward without the rightful space to restore those who directly experienced this massacre–as well as the impact upon we who were a witness and now, now we all must live with yet another level of terror in our blood–which impacts our health, physical, spiritual, emotional. Forgiveness, I am saying, in this nation, lands too often as a tool of white supremacy.

I am writing this to say I need time to heal. I am writing this to say that if I do, I can’t imagine what those who were in the church that night, or their family and friends and fellow congregants need. This above all, is what sits in my heart this Saturday Mourning.

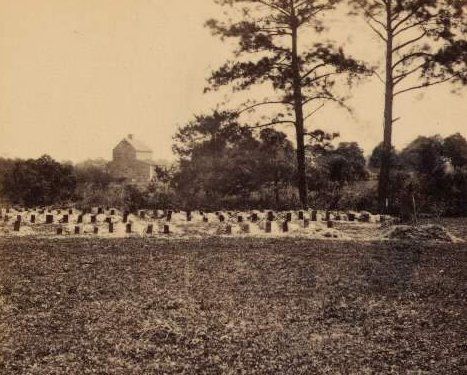

(Photo Credit: Getty Images / Win McNamee)