As the world faces a huge pandemic, it is important to take into account the different resources that various countries and classes have to deal with such an event. The main guidelines so far have been to wash your hands, wear a mask, and maintain at least 6 feet from anyone who is not living in your home. These guidelines were created by organizations like the CDC and WHO without creating plans that can apply to poor, working class people around the world who live in compact communities – aka slums, townships, barrios, informal settlements – where these practices are impossible. COVID-19 has highlighted how much class inequality is a life or death issue and can be, and has been, easily ignored by those with privilege. Those who are members of the transnational capitalist class, such as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and celebrities like Tom Hanks, have continuously pushed these guidelines, using themselves as a model for why everyone should abide by the rules. That’s easy to say when you can get easily tested, when not going to work will not harm your quality of life or prevent you from eating that week, and when you have vacation homes where you can self-isolate.

This pandemic is maintaining global inequality as the guidelines are not an option for people who have to walk a long distance to get to the nearest water source, and those who cannot socially distance from their neighbors. These areas will be hit the hardest, but the news media barely take notice or seem to care. They continue to show the horror of NYC or New Orleans, or the empty freeways crossing U.S. cities. In order to counteract a pandemic of this sort, we must look out for everyone, especially those who are most vulnerable. In this instance, I am not talking about the elderly; I am talking about those who make up the low-waged working classes, those who do not have the luxury of Postmates, Instacart, or Amazon.

The media plays a huge role in whose stories or concerns get airtime, structuring how the rest of the world responds as well.

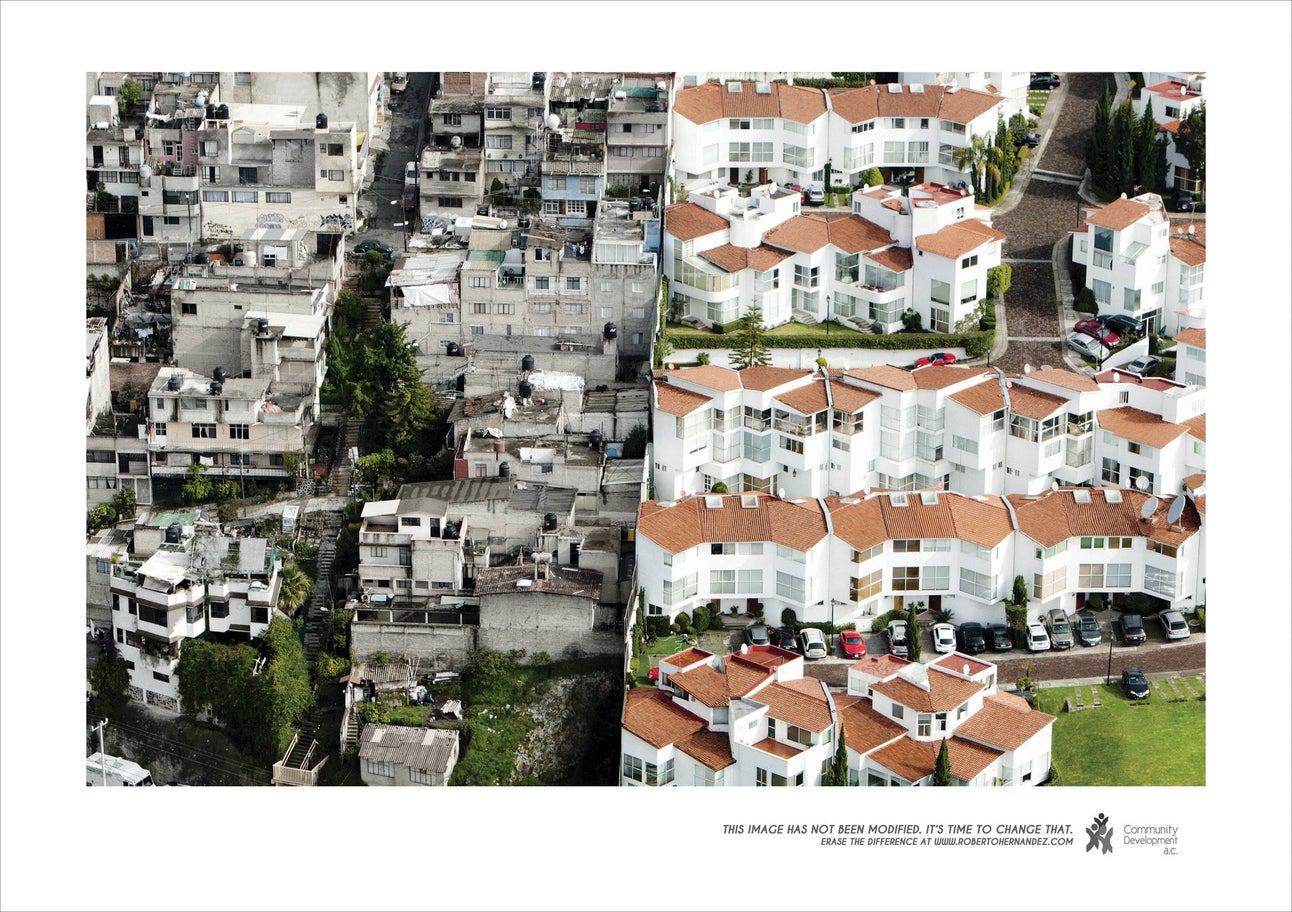

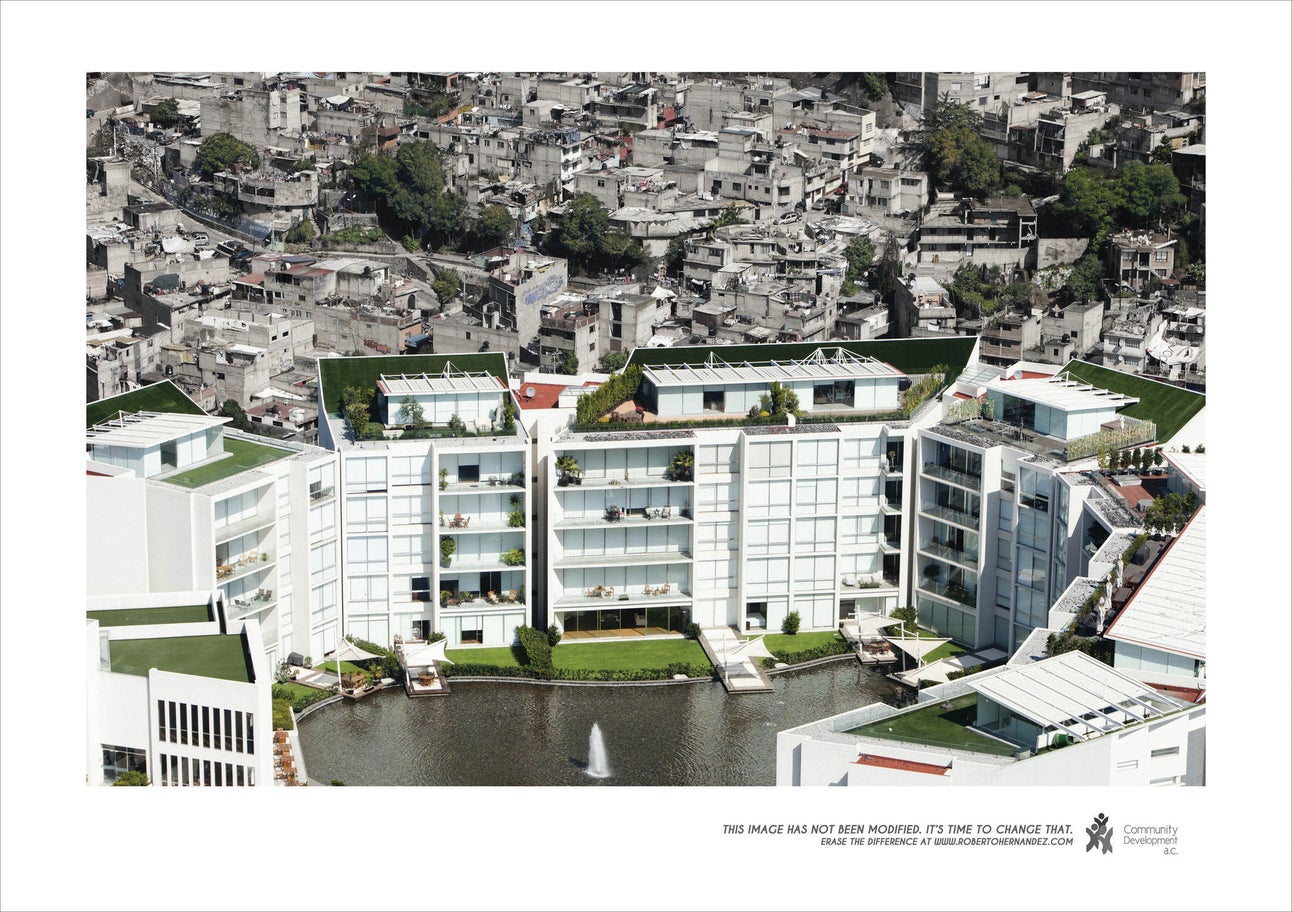

We have seen how they have only allocated one day of news coverage to the Black community even though they are one of the hardest hit groups in the U.S. It is not a mystery why the media leaves out certain groups, those executives who are members of the transnational capitalist class ultimately decide whose story matters and repress anything that challenges the current global economic conditions. To make a universal difference, we need to give equal time to all vulnerable groups. We need to structure guidelines with more consideration for those who are meant to remain in the shadows, hidden, invisible. Start by looking and seeing. Look at the photos accompanying this with show compact communities juxtaposed with middle- and upper- class communities.

(Photo Credits: Independent / Oscar Ruiz / Publicis)