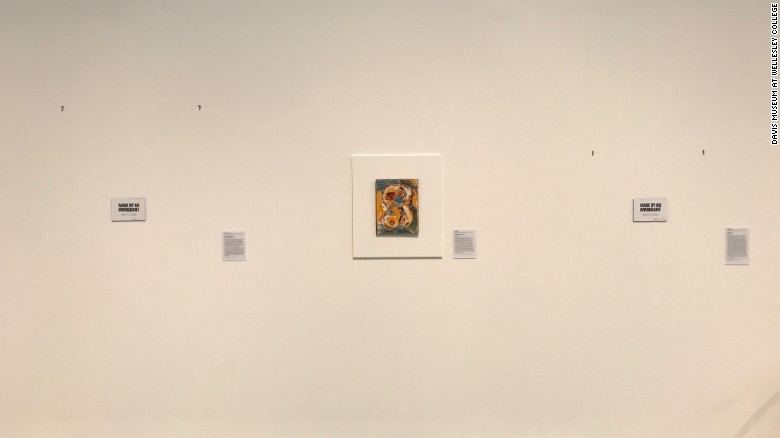

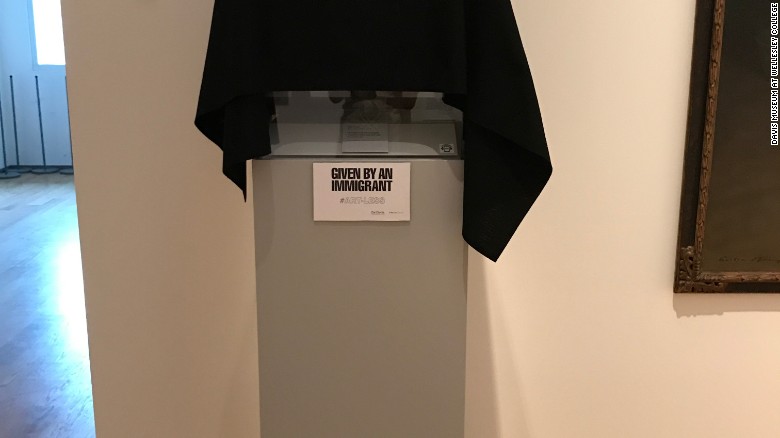

The labels read, “Made by an immigrant”

This is a frightening time for people who care about the essential elements of a democracy: a free press, respect for fellow citizens, civil engagement with each other despite differences, to name just a few. The demonization of the other is particularly disturbing. This is also a time, however, when people of conscience make themselves known and speak up against prejudice and injustice. Which is why I was so delighted to see my alma mater, Wellesley College, highlight the substantial contributions of immigrants to the art of this diverse country. This week I proudly shared the news that the college’s Davis Museum had removed, or covered with black fabric, every piece of art created by an immigrant to the US. Why do I feel that this symbolic gesture is so powerful and why does it mean so much to me?

To call me a proud Wellesley graduate says very little about me. I am also a South African cisgender woman of color, a warrior for social justice, a progressive feminist, a writer, and a legal permanent resident of the United States. I arrived at Wellesley a feminist activist and floundered for two years as I tried to find my feet in that predominantly white, upper middle-class, wealthy milieu. I was so different from my classmates: two years older because I had taken ‘A’ levels after high school in the hope of getting into a British university; the product of a highly-politicized society and a high school with a long history of political activism (when Soweto exploded in 1976, I was in 11th grade). But, eventually, I made a place for myself. How? Because my peers embraced this person with the weird accent who looked Asian and called herself ‘Black,’ who argued that newspapers sometimes lied and often concealed, who said one should defy morally illegitimate laws, who loved the music of Janis Ian and Frank Sinatra. They listened to me, I listened to them: we found a way to be friends. We’re still talking: 37 years later a group of Wellesley ‘84s in the DMV meets regularly for dinner.

It also helped that the college was an affirming place for women and that I met faculty and staff who shared my worldview. Those professors have remained my friends. At lunch last summer I told the faculty member who influenced me most profoundly that, in my first class with her, “I felt my brain explode.” The feeling of kinship—intellectual, political, personal—was instantaneous, deep, and endures to this day. Which is why Wellesley means so much to me. She has given me so much and I feel part of her. And then, to have her embrace being home to “a bunch of dykes,” turn it around and proclaim the achievements of that same “bunch of dykes” tells me that my alma mater is still the open and inclusive environment I graduated from all those years ago. Wellesley’s visible recognition of contributions immigrants have made to art says, “This is what we lose without them here.” That is a powerful message.

(Photo Credit: CNN)