In November, a study appeared, “Still nothing to see here? One year update on prison deaths and FAI outcomes in Scotland”. As the title suggests, a year earlier, the same research team produced, “Nothing to see here? Statistical briefing on 15 years of FAIs into deaths in custody”. FAIs are Fatal Accident Inquiries, which, since 2016, are required for all deaths in custody. In 2015, the Inquiries into Fatal Accidents and Sudden Deaths etc. (Scotland) Act 2016 was passed and signed into law in 2016. Its intent was to regularize and speed up the holding of inquiries on the job as well as in custody. At the same time, the hope was such a regularized system might also shed some insight into the pattern of deaths, both at work and in custody. In 2019, it was noted, “The passing of the Act has made absolutely no difference.” The recent reports suggest that assessment was either premature or too kind. Since 2016, the situation has worsened, considerably. In that deteriorating climate, where are the women?

“Still nothing to see here?” begins” “There were more deaths in prison over the past three years than in any other three-year period in Scottish prison records: 121 people died in prison between January 2020 and September 2022 compared to 98 deaths between 2017-19, and 76 deaths between 2014-16. Covid was not the main cause of the increase in the current period. Suicide and drug-related deaths are the driving forces in rising levels of death. Together, they were the leading cause of death in prison in 2022. Comparison with earlier periods shows that the chance of dying in prison in 2022 is double that for someone who was in prison in 2008. Rough comparisons with England and Wales show Scotland’s prisons had higher rates of deaths due to Covid, suicide and drugs.” As to FAIs, the situation has remained abysmal. The inquiries tend to take over two years to complete and almost never provide insight into means of prevention.

While Covid impacted the prisons, the main cause of death, again, was suicide and drugs. “Suicide is the leading cause of death of women in prison.”

The report notes that too often “very unwell people, who did not clearly present a threat to public safety” are detained. Often, they die: “These cases raise further issues of care and dignity in custody.” Here is one such case: “Police were called by members of the public reporting a woman wandering, confused and cold in pyjamas and a coat on a cold autumn evening. They had given her a cup of tea when police arrived, who on checking her record and noting outstanding warrants (for theft), arrested her. She was moved through three different police offices over several hours that night, and at each of these a flag on her record of medical issues requiring her to be seen by a health care professional whenever in custody was missed. The next morning she was taken to court where she spent seven hours waiting in a holding cell. By the time of her court appearance late in the day she could not stand or walk unaided and was placed in a wheelchair where she sat ‘slumped’ as the Sheriff denied her bail. After her bail hearing she was returned to the court holding cell, her health deteriorating for another two hours. At this point paramedics were called and arrived, and she was taken to hospital, where her health continued to deteriorate and she died six days later, never leaving hospital. No corrective findings made.”

The people who found this woman gave her tea. The police put her behind bars. No corrective findings made. According to the earlier report, between 2005 and 2019, “not a single FAI in the case of a woman dying in prison made a finding identifying any precautions, defects or recommendations.” What else is there to say?

In December 2016, the prisons established a suicide prevention strategy called “Talk to Me”: “following the introduction of the Talk to Me strategy there have been 42% more suicides than before it came into effect”. What else is there to say? Again, in Scotland, suicide is the leading cause of death of women in prison. Has been, continues to be.

In 2021, research, funded by the Scottish government, found that 78% of incarcerated women in Scotland suffered from significant head injury, most of which was caused by sustained domestic abuse. How did the government respond to this? Silence. More incarceration, more suicide. What then is the value of a woman’s life? Of women’s lives? Their deaths in custody, where inquiry is mandated, result in nothing, less than nothing, in terms of learning, insight, concern, care, and, if anything, an assault on their dignity and that of their loved ones. How many more reports, studies, commissions are needed? Stop sending women to prison. Don’t close one only to open another. Close them all and rediscover justice.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

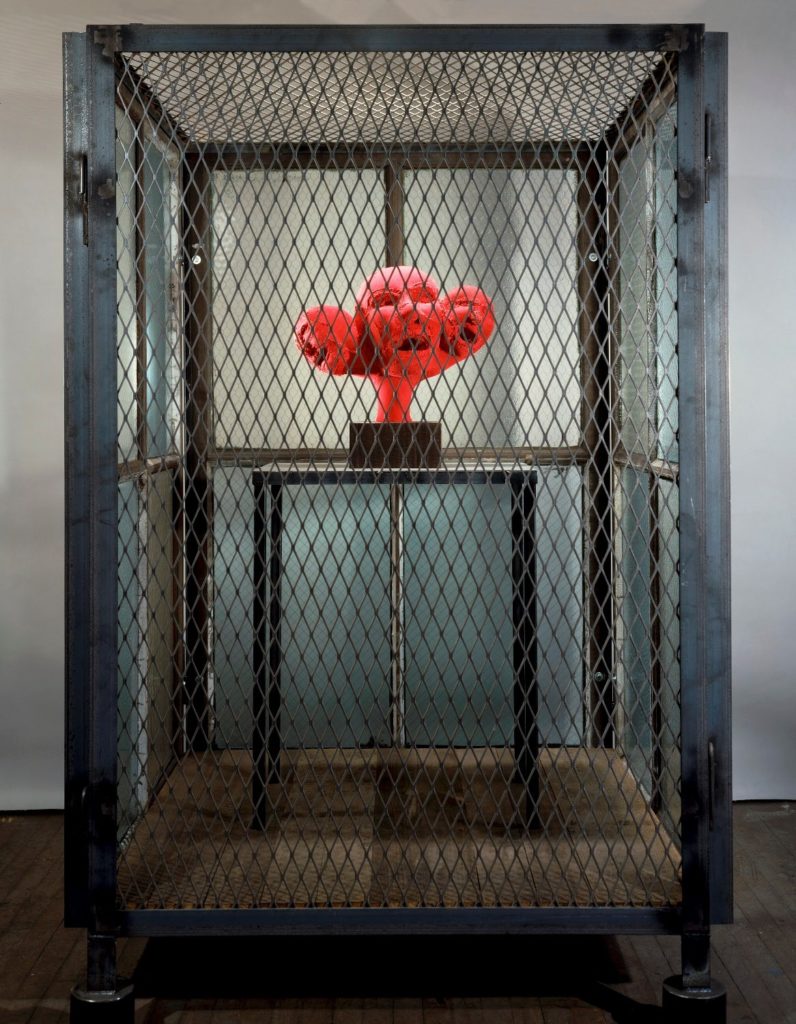

(Image Credit: Louise Bourgeois, Cell XIV (Portrait) / National Galleries of Scotland)