On Monday, January 8, 2023, after more than two and a half years of deliberating, and not deliberating, the New Jersey General Assembly finally voted on and passed the New Jersey Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights, 47 – 26. Monday was the last day of the legislative session. The bill was passed out of committee on January 4, the last day the committee could hear and decide on whether or not to pass the bill onto the general body. As one domestic worker/organizer said, “They put us last minute because we were there with our presence”. This bill was first introduced June 2021. For two and a half years, and longer, domestic workers showed up, pushed, persisted, shouted, whispered, sang, linked arms, advocated, mobilized, organized, organized, and organized. They were there with their presence. As domestic worker/organizer Sandy Castro explained, “It’s a very big win for us. It feels good to see it come to fruition after sacrificing so much time, so many days, to continue this fight”.

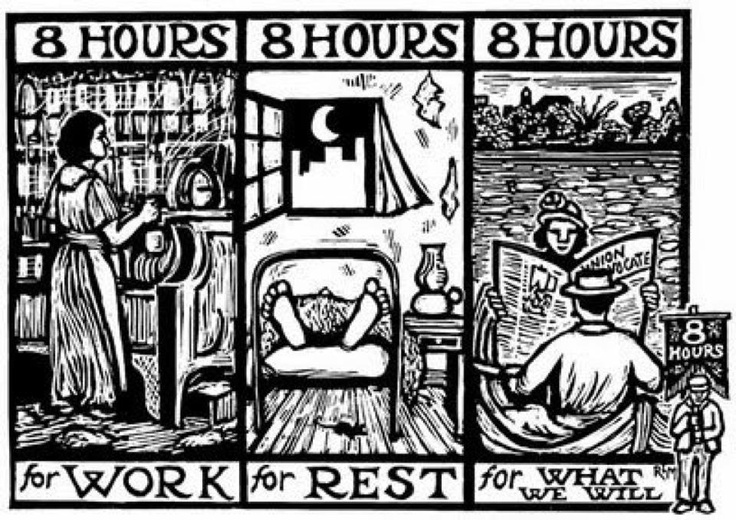

The New Jersey Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights provides domestic workers protection against discrimination, harassment, and retaliation; ensures mandatory meal and rest breaks; and requires written agreements that establish, detail, and document hours, wages and duties. Employers will have to pay workers no less than the state minimum wage, $15.13 an hour. The new law creates a board to monitor and review the implementation of the legislation and make recommendations to improve it and provides for the enforcement of domestic worker rights. Finally, the new law ensures advance notice of termination and provides other protections for live-in workers, such as privacy and anti-trafficking safeguards. In other words, domestic workers are workers. The centuries long era of exclusion is coming to an end … finally.

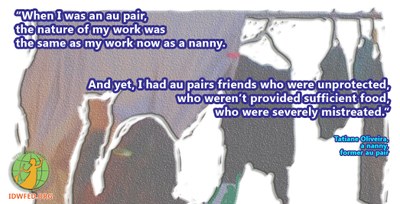

In 2020, Rutgers University Center for Women and Work issued a report, Domestic Workers in New Jersey, which found, unsurprisingly, “domestic workers are predominately female with a high proportion of immigrants and women of color. This is especially true for New Jersey, where domestic workers are even more likely to be female, immigrant, and non-white compared to the U.S. national average. In New Jersey, 97 percent of all domestic workers are female, 52 percent are immigrants, and 60 percent are non-white.” The report also found that the top three reasons domestic workers did not take action against labor violations were, in descending order, “Did not know how”; “Did not know I could”; “Afraid I would lose my job”. The new law establishes structures to educate both workers and employers concerning the law. Eliminate not knowing and fear, you eliminate over 60% of the respondents’ reasons for not contesting and reporting labor violations.

New Jersey joins ten other states that have some version of a Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights: New York, California, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Oregon, Illinois, Nevada, New Mexico, and Virginia. New York passed its Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights in 2010; Virginia, in 2021. As domestic worker/organizer Evelyn Saz explained, “This bill is a critical step toward justice, not only for us in New Jersey but for domestic workers across the nation. We deserve to work with protections, dignity and the respect we have rightfully earned.” They came with their presence … and they won for workers across the nation.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: National Domestic Workers Alliance)