The momentum for women in Pennsylvania to get commuted from their life without parole (LWOP) sentence has diminished. Even with commuted lifer Naomi Blount hired to assist women filing their applications by Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman who heads the PA Board of Pardons (BOP) women are still being denied a merit review. This prevents them from getting a public hearing. Life sentenced Sheena King and co-creator of The Women Lifers Resume Project of PA asks: “Why isn’t mercy extended more to women? Are we somehow less deserving than men?”

Without a doubt women serving LWOP in PA believe they are being further marginalized, revictimized by the judicial and political patriarchy resulting in their criminal behavior judged much harsher than men. They are seen as a greater threat to public safety and being totally irredeemable. Even for a woman with a second-degree felony conviction 30, 40, 50 years ago the chances of her getting commutation is practically impossible.

- Can a scent recalled nearly 30 years ago by someone who didn’t witness the murder be enough to deny a woman commutation? Yes!

- Can a broken pane of glass that enabled a woman to walk away from an unsecured prison perimeter nearly 40 years ago be enough to deny a woman a public hearing? Yes!

- Can a prison report by biased personnel deny a woman the support she may need to get a public hearing weigh enough to deny her this opportunity? Yes!

- Are medically compliant women with a mental health diagnosis being denied a public hearing? Yes!

- Are women who killed their infants during a postpartum episode nearly 40 years ago getting denied a public hearing? Yes!

- Do women who are fragile octogenarians have a greater chance of commutation? No!

Before Fetterman arrived on the BOP grassroots advocates did statewide public campaigns to show their support for commutation. Since he came into office, advocacy has been less public: no more mailing in hundreds of postcards or printing t-shirts is required; social media has taken over. The rules have been tweaked to apply for commutation though it’s no less arduous. The various offices that represent victims have been put on notice to do your job-you got 90 days to find the victims to oppose commutation and you have to show your work. So no more accusations by victims that have said we weren’t notified!

The BOP has been doing public hearings online since the pandemic began. As a result, I have noticed the absence of supporters giving testimony, lethargic testimony in support by staff at the prisons and rambling testimony by the victims with incorrect information. Even the BOP seems to be empowered by the lack of in-person testimony; more vocalization and pleading to members for a likeminded vote by other members. Since the BOP doesn’t meet as a body to discuss the merits of an applicant before voting Fetterman feels a last-ditch attempt to get to a public hearing by admitting that his yes vote comes from mercy! “Come on! This person is old and terminally ill!” To Fetterman this is consensus building. It never works. It’s just so pathetic and amateur to witness!

To raise the numbers of women getting commutation I feel can only occur if the BOP interviews each and everyone before the merit review. Like Sharon Wiggins once said, “How can I get commuted by writing a few paragraphs?” Commutation is the only way the state can release a life sentenced women unless she beats her conviction or her sentence is found to be unconstitutional and lastly, through medical parole where a doctor predicts her death within a year and is non-ambulatory.

(Ellen Melchiondo writes in the capacity as a co-founder of The Women Lifers Resume Project of PA.

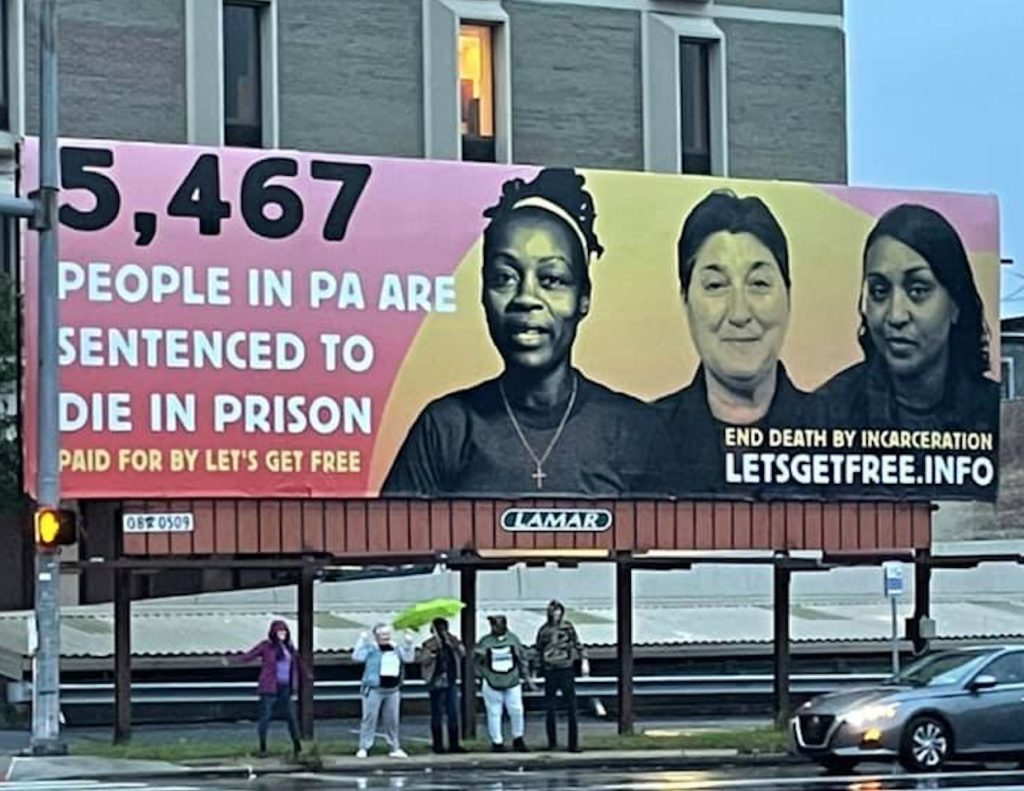

Photo by CADBI-West depicts Tameka Flowers, Charmaine Pfender and Sarita Miller. Billboard image comes from stills in videos produced by Let’s Get Free and Women Lifers Resume Project: “You Deserve Better Than Prison” and “We Are More Than Our Worst Day” Videos can be viewed at www.wlrpp.org

Thanks to etta, Darlene and Elaine for their editing of this essay!)