“And Babylon, so many times destroyed.

Who built the city up each time? In which of Lima’s houses,

That city glittering with gold, lived those who built it?

In the evening when the Chinese wall was finished

Where did the masons go? Imperial Rome

Is full of arcs of triumph. Who reared them up?”

Bertolt Brecht, A Worker Reads History

In 1936, Bertolt Brecht asked, “Who built the city up each time?” A recent report brings this question roaring back. According to Cities Where Construction Workers Would Have To Work the Longest Hours To Afford a Home, conducted by Construction Coverage, nationally, a construction worker would have to work 54 hours a week to afford the mortgage on a median priced home. Needless to say, that picture changes drastically, depending on where one goes. For example, Virginia construction workers have to work 66 hours a week to afford a median priced home in the area in which they work. According to the study, Washington-Arlington-Alexandria is even worse. Construction workers have to work 80 hours a week to afford a median priced home. Virginia is the 13th most unaffordable state for construction workers. Washington – Arlington – Alexandria is the tenth most unaffordable metro area, but only by a hair. The fifth through the eleventh most unaffordable metro areas are pretty much clustered together, from 84 to 80 hours a week.

As the study notes, “The construction industry is facing a major worker shortage. Associated Builders and Contractors—a national construction industry trade association—estimates that the industry will require an additional 454,000 new workers on top of normal hiring to meet the booming demand in 2025. However, despite the substantial need for more construction professionals, elevated home prices and an inadequate homebuilding pace are making it difficult for construction workers to afford to purchase a home in the cities where they work.”

Where did the masons go?

(By Dan Moshenberg)

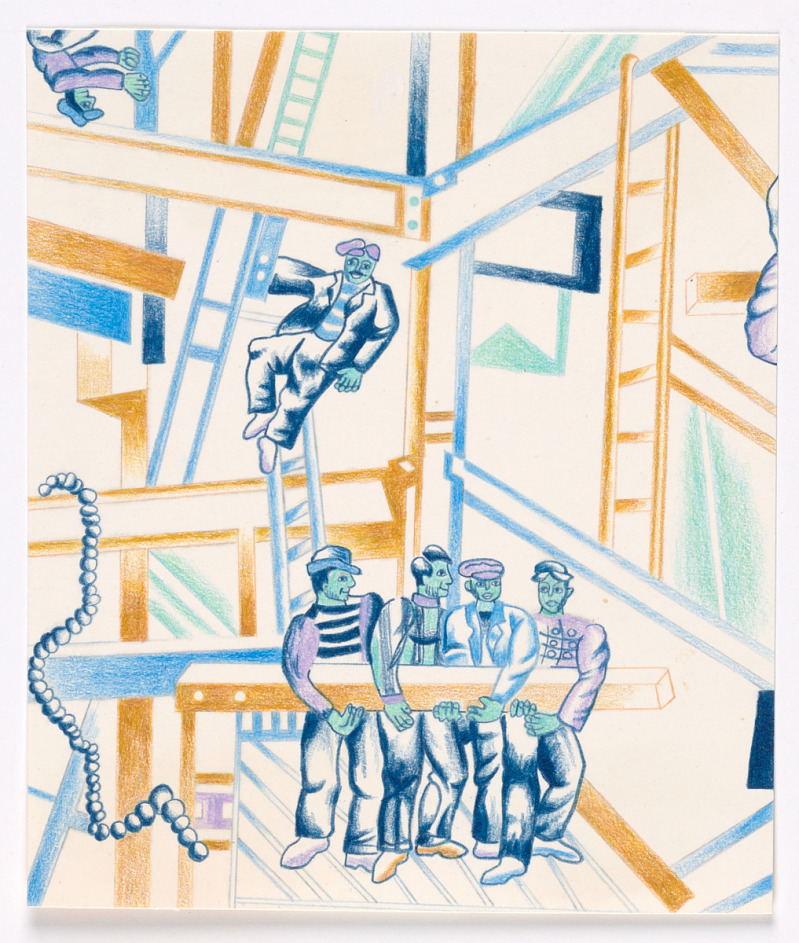

(Image Credit: Terry Gentile, Design for a Textile, Construction Workers / Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)