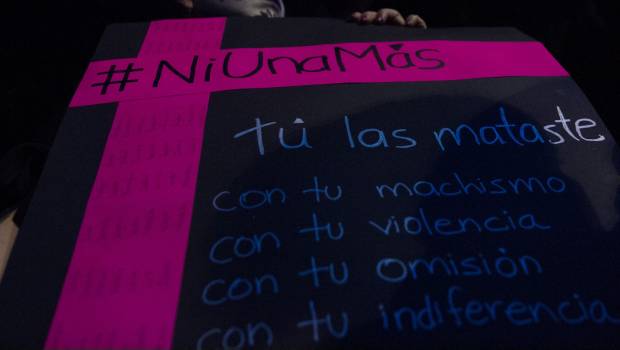

After Hurricane María, the number of femicides in Puerto Rico started increasing at an alarming rate. Disappearances and femicides of women are ongoing issues in Puerto Rico, which has one of the highest femicide rates in the Western Hemisphere. But it was not until two years later, in 2019, that this was brought to public attention (in the continental United States). Gender-based violence calls to attention the consequences and history that colonialism, transphobia, racism, and sexism have on the island. Currently, women and feminists’ group like La Colectiva Feminista en Construcción have repeated their demand for a declaration of a State of Emergency against gender violence on the island but the Puerto Rican government has only recently acted on these demands, yet these efforts have not been sufficient; killings and disappearances of women on the island keep increasing and becoming common.

History is important and can be an act of resistance, but it is also about power; how it upholds the victories of the colonizer, not the colonized. Within the social contexts of Puerto Rico, heteronormativity is colonized by religious principles and gender-based perceptions that in recent years have caused an escalation of violence against transgender women and reports of anti-transgender violence, especially femicides. Along with the temporal displacement of Blackness and Black bodies that is closely connected to State modernizing agendas, Puerto Rico’s police has a history of marginalizing Black people without any consequences within the law, especially when it comes to racial profiling and recent police killings of Black (including LGBTQ+) Boricuas.

The history of colonization in Puerto Rico is not as buried as some are led to believe. By being aware of the history and current ways in which colonization is incorporated, there is resistance and a foundation for radical freedom on the island. Conversations about race and gender, however, need more work. Ethnicity and nationality are focal point in conversations about race, therefore causing erasure. Consequently, as a way to not talk about race, Latin America pushes its citizens to think of themselves in terms of their ethnicity and nationality. Puerto Rican’s acknowledge their history of Blackness; however, it is along admitting their Spaniard and Indigenous roots first, and Blackness last. Awareness about the danger trans women faced during the femicides is there, but no discussion as to why or how transphobia plays a part in it. Instead, trans women are placed into a generalized “all women in Puerto Rico are in danger” category, equating their fear and likelihood to femicide to cis women, which is highly problematic.

And the government needs to be held accountable. As of January of 2021, the Puerto Rican government has issued a State of Emergency due to gender violence, yet these efforts have not been sufficient; killings and disappearances of women on the island keep increasing and becoming common. In order to take accountability, the government should provide more resources (including legal protection, housing, and financial support) to survivors of femicide, domestic violence, and any form of gender violence. A relationship and conversation between the State, survivors, community organizers, and the people of Puerto Rico must be formed in order to hold the Puerto Rican government accountable and responsible.

(By Glorimar Mariño)

(Image Credit: Michelle Dersdepanian / TodasPR)