“If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse, and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

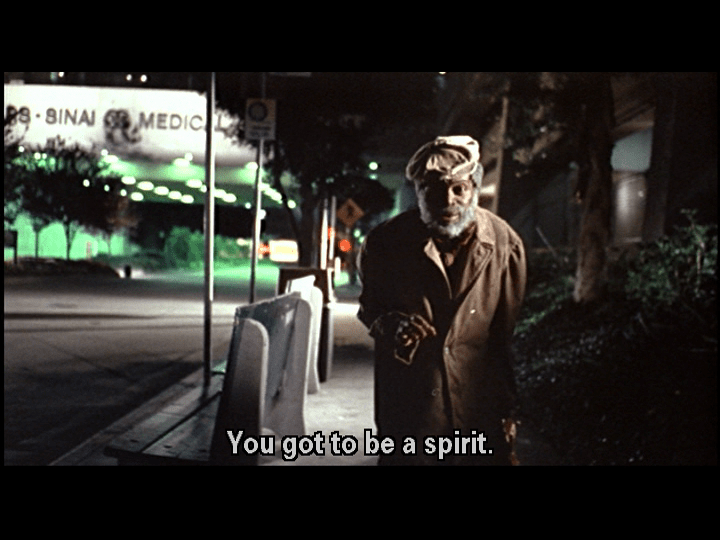

According to a headline in today’s New York Times, “More Universities Are Choosing to Stay Neutral on the Biggest Issues”. According to the report, “148 colleges had adopted “institutional neutrality” policies by the end of 2024”. There is no neutrality here, there is, at best, compromising of values foundational to the liberal arts. In the immortal words of Rastaman, played by Amiri Baraka in the film Bulworth, universities have chosen to be ghosts in a time when we need spirits.

Neutrality: not taking sides in a controversy, dispute, disagreement, impartial, unbiased. Neutrality: In relation to war or armed conflict: not assisting, or actively taking the side of, any belligerent party, state, etc.; remaining inactive in relation to belligerent powers. Neutrality: Not belonging to or controlled by any belligerent party, state, etc.; belonging to a power which remains inactive during hostilities; exempted or excluded from the sphere of warlike operations.

Universities who “choose to stay neutral” have chosen sides, and not only in the matter of Palestine and Israel. They have chosen to be the property of major donors. They have chosen to forsake inquiry, debate, difficulty for … for what? Survival? As what? As ghosts of their former selves. They have chosen the elephant, and the mouse will not thank them.

In the twentieth century, thinker after thinker decried the claim of neutrality in periods of crisis, especially those of mounting state violence. Desmond Tutu stands in a crowd of righteous survivors and martyrs who faced injustice and oppression and warned against the neutral stand. In the seventeenth century, Robert Herrick wrote Neutrality Loathsome.

Neutrality Loathsome

God will have all, or none; serve Him, or fall

Down before Baal, Bel, or Belial:

Either be hot, or cold: God doth despise,

Abhorre, and spew out all Neutralities.

From Herrick in the 1600s to the Rastaman today and beyond, spew out all neutralities! You can’t be no ghost! Be a spirit!

(By Dan Moshenberg)