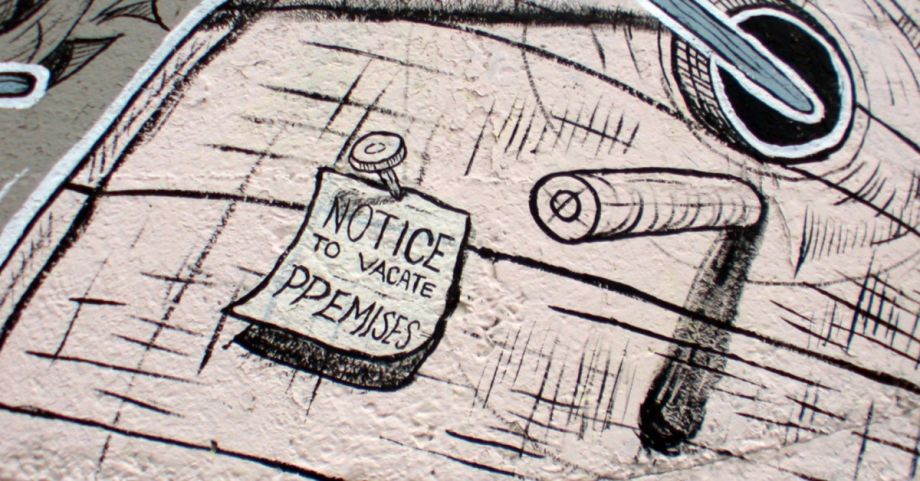

“Housing should not be a privilege”. After years in shelters and on the streets, 41-year-old Dwayne Seifforth and his nine-year-old daughter D’Kota-Holidae Seifforth live in an apartment in Harlem, in upper Manhattan. Having a stable and decent place to live has made all the difference. Mr. Seifforth moved from working part-time and living on food stamps to a full-time job. His daughter went to school and settled in. Unbeknownst to them and their neighbors, the landlord’s ownership of the building was tenuous, at best, and now they face eviction, through no fault of their own. “Housing should not be a privilege”. It’s a sentiment expressed around the world, and, sadly, with increasing frequency, given the rise this year in mass evictions. Consider just the last month or so, 2022.

In the United Kingdom, November ended with the revelation that, in the depths of the pandemic and its economic and existential hardships, housing associations, home to hundreds of thousands of vulnerable tenants, had secretly lobbied the government to let them charge more rent. At the same time, the typical salary for a housing association executive was around £300,000 a year, close to $400,000. At the same time, Michael Gove, the `levelling up’ secretary, reported that `at least’ tens of thousands of rental properties across the UK were unsafe, due to lack of maintenance. One minister’s “lack of maintenance” is a thousand landlords’ refusal to maintain. Meanwhile, end of the year reports showed that no-fault eviction notices rose 76% in the past year. 48,000 households in England alone were served with no-fault eviction notices.

In Canada, evictions marked the end of the calendar year. Quebec’s non-urban areas saw a marked increase in “renovictions”, forced evictions under the pretense of renovation. Non-urban Quebecois renovictions rose 43% in the past year and look to continue rising. The Coalition of Housing Committees and Tenants Associations of Quebec describes the situation as “alarming”. In metropolitan Quebec, evictions rose from 1,041 in 2021 to 2,256 in 2022, a 154% increase, again in the midst of a pandemic and its hardships.

For the state of Assam, in northeast India, in December, the state went on an eviction spree, and this in a state that has used mass evictions often since May, 2021, when the BJP assumed power. These eviction campaigns have targeted `encroachers’, who are almost Muslim. At the time of the last census, Assam’s population was around 27 million, of whom around 19 million were Hindu and 11 million were Muslim. From May 2021 to September 2022, 4,449 families have been evicted, almost all Muslims of Bengali origin, most of whom have lived in the area for generations. In November, 562 families were evicted from one site, without notice. In the first week of December, 70 families were evicted. On December 19, another 302 families were evicted. On December 26, 40 families were evicted from one site. On December 28, another eviction drive was announced, in Guwahati, Assam’s most populous city. Repeatedly, the government and its supporters have boasted that there was no resistance to the evictions.

Finally, on December 17, a group of people identifying themselves as part of or related to Operation Dudula, an anti-immigrant group in South Africa, invaded a derelict building in the New Doornfontein neighborhood of Johannesburg and evicted over 300 people, almost all migrants. Included among those cast out were more than 60 people living with disabilities, most of whom were blind, and over 200 women and children. As in Assam, the purpose was to remove `encroachers’ who were somehow `foreign’.

That’s the end of 2022, along with mass evictions of slum dwellers in Nigeria, villagers and small shop owners in Cambodia, Afghan refugees in Greece, long term residents in Mexico forced out to `welcome’ the new remote workers from the United States and Europe, Palestinians across the occupied West Bank, and especially Jerusalem, and, in the United States, from Connecticut to Oklahoma to Missouri to California to Oregon, and beyond and between, eviction filings and evictions are surging, often to record heights. When it comes to access to decent, stable, and affordable housing, the world map is one of violence, devastation and existential crisis.

Globally, the common theme is fear. In India, for example, the government assured the world that everything was fine because there was no resistance. According to residents, the reason there was no resistance was years of police violence against those who protested. Ajooba Khatoon, whose house was demolished, explained, “We did not resist them because there were hundreds of policemen. The police had already instilled a sense of fear among us since their arrival on December 13. We were not allowed to step outside on the eviction day.” Across the United Kingdom, renters live with dangerous conditions because they are fearful of revenge evictions if they speak up. In South Africa, one of the survivors of the eviction in Johannesburg, Lazarus Chinhara, explained, “‘We are not scared of deportation or anything. If we remain quiet, we will become prisoners of conscience.” Tadiwa Dzafunwa added, “I don’t know if we will ever recover from this”.

Around the world and around the corner, neighbors are living with histories of State violence, perpetrated by landlords with the assistance of the police. Thinking of the residents’ and the world’s silence at the evictions in Assam, Moumita Alam wrote, “The silence around eviction however can be attributed to the history of violence that has marked the fate of the protestors …. If every protest begets dead bodies to be buried in silence, ‘peace’ of the burial ground shrouds our memory.” If we silently accept the forced disappearances of neighbors, the web of trauma thickens and tightens as the corpses pile up. What threatens all that is human is the cooperative architecture of violence, silence, and trauma of eviction. I don’t know if we will ever recover from this. Housing should not be a privilege.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Image Credit 1: Next City) (Photo Image Credit 2: LibCom)