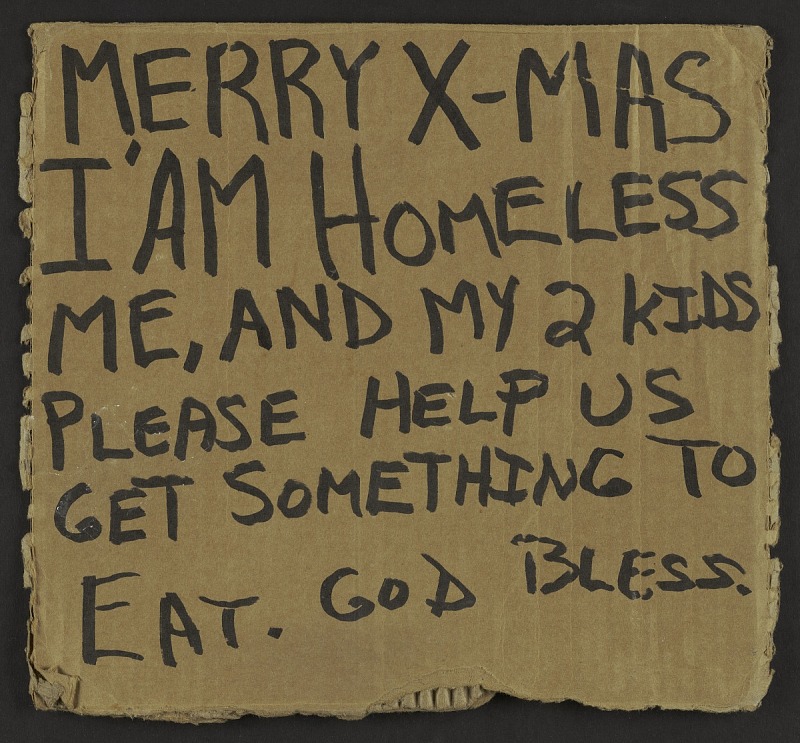

A sign collected in the Georgetown area of Washington, DC by a Smithsonian employee.

This week, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Policy Development and Research released its 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report. The report takes a one-day image of homelessness on a day in January 2024, a so-called Point-in-Time, or PIT, count. The picture is predictably grim. From 2023’s count to this one, homelessness rose by 18%. The report opens: “The number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night in 2024 was the highest ever recorded. A total of 771,480 people – or about 23 of every 10,000 people in the United States – experienced homelessness in an emergency shelter, safe haven, transitional housing program, or in unsheltered locations across the country. Several factors likely contributed to this historically high number. Our worsening national affordable housing crisis, rising inflation, stagnating wages among middle- and lower-income households, and the persisting effects of systemic racism have stretched homelessness services systems to their limits.” Additional factors include “public health crises, natural disasters that displaced people from their homes, rising numbers of people immigrating to the U.S., and the end to homelessness prevention programs put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the end of the expanded child tax credit.” Top of the list of causes is “our worsening national affordable housing crisis”. Remember that: “our worsening national affordable housing crisis” is the first element contributing to historic levels of homelessness. The lack of affordable housing, not a putative “surge of asylum seekers”.

News media headlines, such as The New York Times, “Migrants and End of Covid Restrictions Fuel Jump in U.S. Homelessness” and Bloomberg, “Migrant Crisis Pushed US Homelessness to Record High in 2024”, would have you believe that migrants, asylum seekers, refugees caused homelessness in the United States. Some news outlets actually got the story right. NPR, for example, explained, “To explain this rise, HUD officials and others point, above all, to the skyrocketing rents that we’ve seen in the past few years. They also cite the recent increase in migrants coming to the U.S. without a place to live, especially migrant families, and extreme weather disasters, for example, the fire in Maui last year.” CBS News reported, “Homelessness in the U.S. jumped 18.1% this year, hitting a record level, with the dramatic rise driven mostly by a lack of affordable housing as well as devastating natural disasters and a surge of migrants in some regions of the country.” Again, the reason people are homeless is because they can’t find a place to live. Nowhere to go, and, often, no one to help.

To return to the HUD report, the Point-in-Time count also found that nearly all populations reached record levels. People in families with children had the largest single year increase in homelessness. Nearly 150,000 children experienced homelessness on a single night in 2024, reflecting a 33% increase over 2023. Between 2023 and 2024, as an age group, children experienced the largest increase in homelessness. About 20% of those 55 or older were homeless on the night of the point-in-time count. “Nearly half of adults aged 55 or older (46%) were experiencing unsheltered homelessness in places not meant for human habitation.”The only population to report a continued decline in homelessness are veterans? Want to know why? “These declines are the result of targeted and sustained funding to reduce veteran homelessness.”

It’s not a pretty picture, and no one thought it would be, but it needs to be reported accurately. Yes, late in 2023 and into early 2024, there was a marked increase in the numbers of people entering the United States seeking asylum. In 2023, there was also a record number of people forced to abandon their homes due to tornadoes, hurricanes, floods, fires and other so-called “natural disasters.” Additionally, there was a record number of people 55 years or older being evicted. In various parts of the country, eviction filings reached historic levels. Some might say there was a “surge” in eviction filings. Who or what is behind that surge? Many argue that the unprecedented entry of corporate landlords and hedge funds into the rental market has been a key factor, given that corporate landlords tend to be serial eviction filers, often making up more than half the eviction filings in any given jurisdiction.

The stories we tell, the stories we are told, matter. In a period of rising xenophobic violence, we don’t need stories that misreport the impact of migrants on the social fabric. Migrants did not cause historic levels in homelessness. “Our worsening national affordable housing crisis” did: skyrocketing rents, fewer homes for sale or rent, mounting eviction filing and eviction rates, and a general acceptance of “nowhere to go” as a facet of “return to normal”. It’s time, it’s way past time, to tell a better story, one of targeted and sustained funding to reduce homelessness.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: Smithsonian National Museum of American History)