On Friday, June 16, Ontario announced it would no longer allow the federal government to hold immigrant detainees in local jails. At any given moment, Ontario houses around half of all immigrant detainees in Canada, and it has kept them in maximum-security regional jails. Ontario is the eighth province to end the practice of jailing immigrant detainees. Last summer, British Columbia announced it would suspend its contract. After that, Alberta, Nova Scotia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan followed suit. Two weeks ago, Quebec and New Brunswick announced their intention to cancel the contracts. The actual cancellation of contract takes a year. At this point, only Newfoundland and Labrador, P.E.I. and the territories have not announced an intention to cancel their contract. Taken together, these remaining provinces account for less than 1% of immigrant detentions.

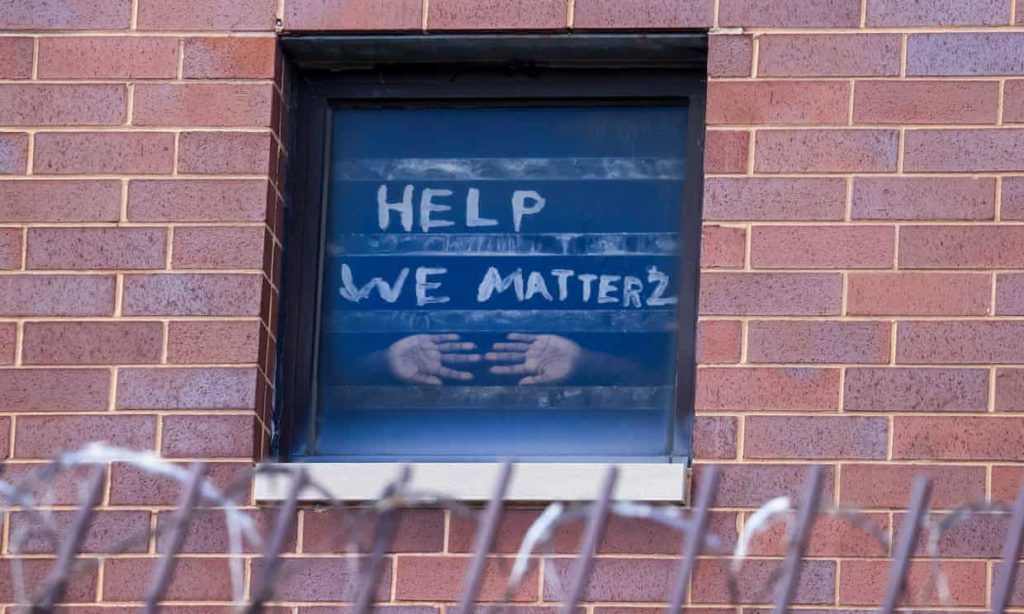

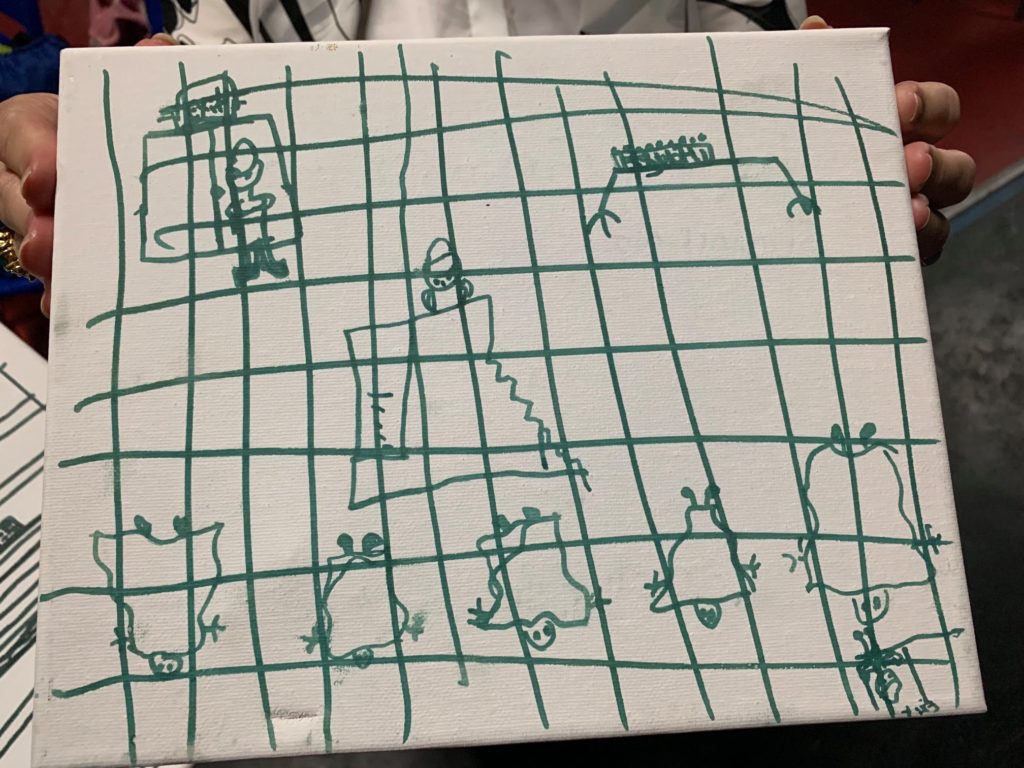

For the past two years, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have campaigned, lobbied and pushed for provinces to act. The campaign is known as #WelcomeToCanada. Two years ago, to the day, they released a report, “I Didn’t Feel Like a Human in There”: Immigration Detention in Canada and its Impact on Mental Health”, which lays out the brutality, cruelty and devastating impact of immigrant detention in Canada. Part of the mental health issue is that Canada allows for indefinite detention of immigrants: “For many detainees, not knowing how long they will be detained causes trauma, distress, and a sense of powerlessness.” Canadian provincial prisons are “notorious for their poor conditions.” As Hannah Gross, Human Rights Watch researcher, noted, “This is an incredible victory. It’s a monumental win for human rights, for migrant and refugee rights.”

And so now the struggle moves to the federal level. First, the Canada Border Services Agency, CBSA, is largely a law unto itself: “The CBSA has sweeping powers including arrest, detention and search-and-seizure without a warrant. It is the only major law enforcement agency without independent civilian oversight to review policies and investigate misconduct.” Year in year out, CBSA incarcerates greater numbers of immigrants. In violation of international law, CBSA separates children from their parents and, further, keeps no record of how many children. CBSA has been found guilty of racial profiling, especially of Black immigrants. As mentioned, Canadian law allows for indefinite detention of immigrants. Teresa Gratton, for example, died October 30, 2017, in immigrant detention, far from her family who had no idea where she was. There was an uproar, momentarily. Six years later, indefinite detention continues. Glory Anawa, several months pregnant, was placed in indefinite detention. Her son, Alpha, was born behind bars. It is reported that his first words were “radio check”. “I don’t even have words to express how I feel. It makes me speechless. I’ve been robbed of my life,” said Glory Anawa. Glory Anawa was imprisoned in 2013. There was an uproar, momentarily. Ten years later, indefinite detention continues.

On March 24, 2023, the so-called Safe Third Country Agreement between Canada and the United States came into effect. Under this agreement, “People entering Canada from the US along the land border are still not eligible to make a refugee claim; will be returned to the US.” These terms “make it more dangerous for people to cross and increase the risk of being detained.” On Friday, June 16, the same day Ontario announced its cancellation of contract with the CBSA, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the Safe Third Country Agreement, while sending it back to lower courts for some clarifications. While the cancellation of provincial contracts with the Canada Border Services Agency is indeed an incredible victory, one to be celebrated, it also casts a light into the ongoing darkness of persecution of immigrants in Canada and beyond. The struggle continues.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: Canadian Council for Refugees) (Photo Credit: The Conversation / Prisoners’ Justice Day Committee Vancouver)