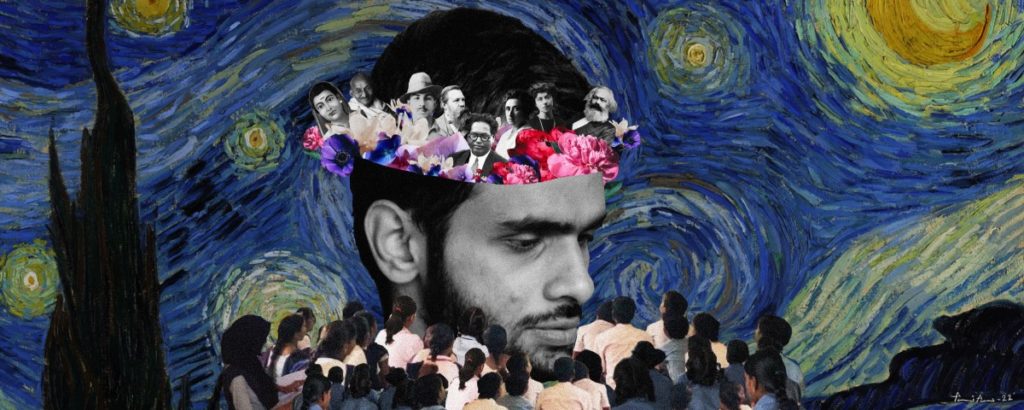

“how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster”

W.H. Auden, “Musée des Beaux Arts“

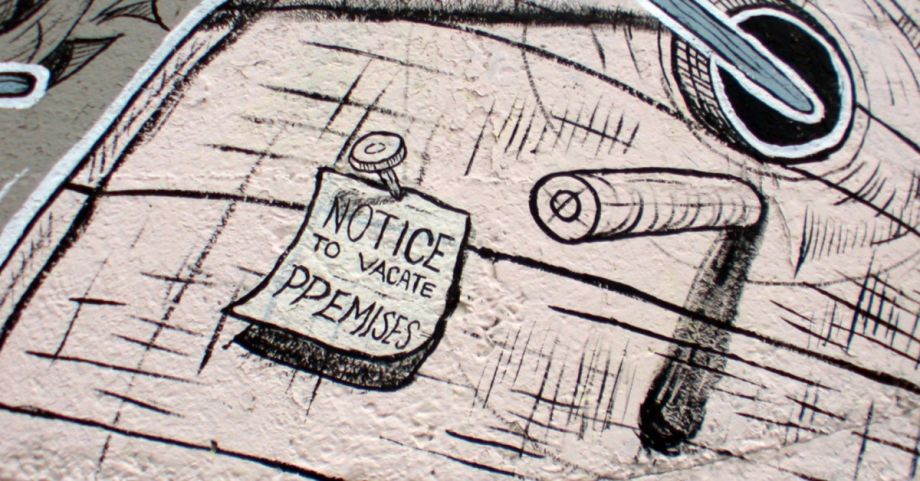

“The stampede at New Delhi Railway station on February 15 that resulted in 18 deaths and left many injured was caused by a lethal combination of factors.” Of the 18 deaths reported thus far, 14 were women. Once again, there was no stampede, but there were many deaths, mostly women and then children. The purported cause will be disputed or determined, but what will not be examined is the gender composition of the mass of the dead. No one will ask, “Why did 14 women die that day, in that way?” In order to find the causes, the cause, of this disaster, it’s important to name it correctly. There was no stampede. There was a massacre of women and children … again.

Stampede is a relatively new word, and it seems to be North American. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, it was coined early in the 1800s, Cowboys in the United States borrowed the Spanish word, estampido, which means crash, explosion, or report of a firearm, and estampida, which means a stampede of cattle or horses. It was an early example of transnational vaquero cowboy culture. The word didn’t come from Spain, it came from Mexico. Stampede, or stompado, was a “sudden rush and flight of a body of panic-stricken cattle” or horses. Later, stampede came to mean a “sudden or unreasoning rush or flight of persons in a body or mass”.

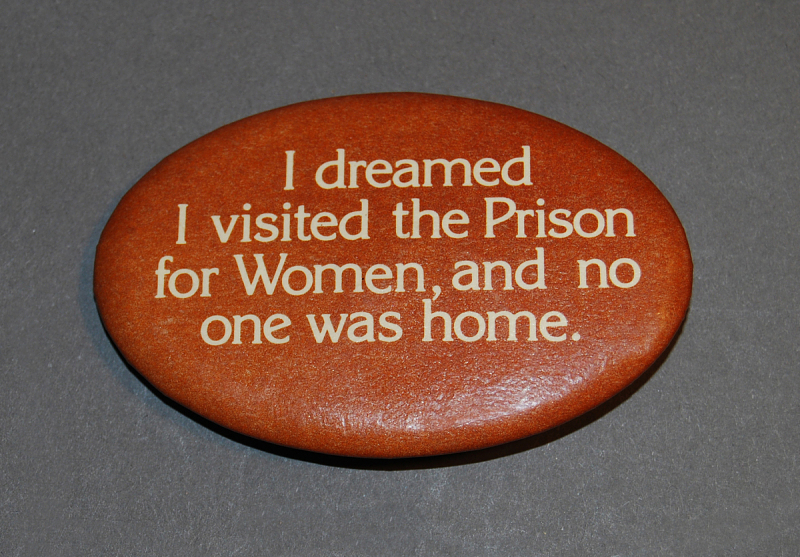

“At its inception, stampede meant a thundering herd, powerful, dangerous. Today, when referring to people, it means a mass of people in flight who are threat mostly to themselves. At the beginning, stampede was virile, masculine, big roaring animals and big riding cowboys. People stampeding was panic. In fact, the word in Spanish for the phenomenon of people rushing as a crowd and crushing one another in the process is precisely pánico. Panic. Sudden, wild, unreasoning, excessive, at a loss and out of control. And what is the term for mass panic? Hysteria, the women’s condition: “Women being much more liable than men to this disorder, it was originally thought to be due to a disturbance of the uterus and its functions”. Hysteric: “belonging to the womb, suffering in the womb”.

What began as an articulation of masculinity, the enraged capacity to destroy all in its path, became the embodiment of womanhood, the helpless implosion of self. What began as a roar became a whimper. When you read that a group was in a stampede, know this. It is not a neutral word. It is a gender, and the gender is woman. Know this as well. There was no “stampede” in India. There was a massacre of women and children in a space and place of human construction.

The report concerning this week’s event concludes: “At least 30 people were killed in a stampede at the six-week festival last month after tens of millions of Hindus gathered to take a dip in sacred river waters.” This is how everything turns away quite leisurely from the disaster, a glancing mention, a wisp of concern, an erasure of women and children, and it’s done. All that remains are the ghosts.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: Pieter Bruegel, the Elder, ” Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” / Royal Museum of Fine Arts)