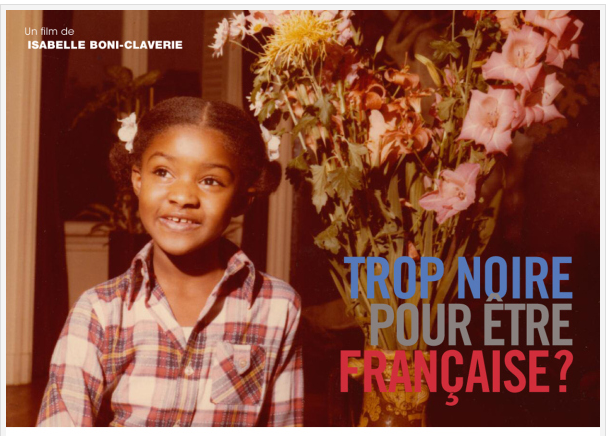

Friday evening on the French/German television channel ARTE, random Black French citizens responded to Isabelle Boni-Claverie a French-Ivoirian screenwriter and film maker, “You know you are Black in France when…” Her latest documentary entitled “Trop noire pour être française ?” (Too Black to be French ?) mixed her personal story with these testimonies and interviews with philosopher Achille Mbembe, historian Pap Ndiaye, sociologist Eric Fassin, socio-demographer Patrick Simon and anthropologist Sylvie Chalaye to explore the experience of being a French Black citizen in the 21st century.

The urge to make this film came after the so-called “affaire Guerlain” in 2010, when renowned perfumer Jean Paul Guerlain explained on French public television how he created a perfume: “I worked like a nigger. I don’t know if niggers have always worked like that, but anyway.” Boni-Claverie was shocked by this comment. Apart from the strong reaction of Audrey Pulvar a “Black” French journalist, the overall press response showed that the remark was accepted as a verbal gaffe and nothing else.

She started an internet-based citizen movement and, along with other movements, organized demonstrations in front of Guerlain headquarter. The movement persisted and grew forcing Jean Paul Guerlain to face justice. He apologized in court saying that he was anything but racist; nevertheless he was convicted.

Boni-Claverie’s documentary explores the idea that his words are jokingly accepted because the stereotype has prevailed in the privacy of what is left of the imaginary of the colonial social construction of France and western countries. She uses her personal family story to untangle the colonial past and mythology that leads to what it means to be Black and French in the 21st century.

The underlying question of her documentary is the absence in France of ethnicity statistics, a necessary tool to see more clearly ethnic discriminations. The question still raises resistance for several reasons: one inherited from the resistance to ethnic murders of the Vichy government during World War II, and the other the belief that blindness to differences will guarantee equality, which is blatantly false.

Boni-Claverie’s personal story and inquiry is nourished with the love story of her grand parents, her grandmother a White law student from rural Tarn, in southwestern France, and her grandfather an Ivorian law student. They defied all stereotypes and laws and got married in 1931 both as French citizens.

France has its own stories to justify colonization, all of them based on the view of the colonized as children and thus not able to run their own lives (just as women). The story of a military defeat against Germany in 1870 also played a major role. As a result, France, a defeated empire, needed compensation in the “unknown lands”. The country sought to annex natural resources and labor force, including canon fodder in Africa as explains Achille Mbembe.

Thus, her grandfather born in 1909 in Ivory Coast, annexed by France, was an “indigene” and although the educative function of the colonies was part of the mythology, education was to be sought in France at the charge of the colonized.

Isabelle Boni-Claverie looks into the fantasizing civilizing mission of the colonizers that has fueled Nicolas Sarkozy’s declarations as a President of France. She replays parts of the infamous speech of Dakar, a slap to the Africans received on their soil. Sarkozy played on the mythologies of colonization to assert that “the African has not fully entered into history”, emphasizing the impossibility of the traditional African man to ever launch himself toward the future.

The “Guerlain affair” occurred during the Sarkozy years in power, with the creation of the national ministry of immigration and national identity, since removed by the Hollande administration. Boni-Claverie inserts a sequence on the role of stereotypes in the colonial construction and how they have persisted and evolved to justify inequalities that are suitable to the French elite and keep French Blacks in questionable citizenship.

In between sequences come the testimonies of anonymous citizens such as this particular one: “You know you are Black when as a member of the staff of a restaurant you must serve the meeting of Le Pen, and you see yourself afflicted with slurs, that you are called cheetah, nigger (negresse), that some throw sugar at you or other cookies and they ask you to pick them up.” This testimony is a reminder of the racist slurs toward Christiane Taubira, the Minister of Justice, and toward Najat Vallaud Belkacem, the Minister of Education.

Sociologist Eric Fassin then reminds viewers that to be French is a question of rights and should not be questioned, as it is written in Article 1 of the Constitution. Isabelle Boni-Claverie asks her relative from the Tarn region about her grandparents and her cousin concludes strongly: You are a Tarnaise! Yes she is in the majority and still…

Playing on the “alchemy of race and rights” the White socio-demographer and the sociologist ask: “Are the Whites ready to become White?” Patrick Simon reminds us that the surface identity is White, and the Whites define the other in comparison with them. He admitted that he questions his own identity, as a White heterosexual male.

At this moment in the documentary the interrogation flips: “You know you are White when a friend of yours goes through ID and is checked and nobody ever asks for your ID.”

Isabelle Boni-Claverie’s grandfather was the first French magistrate of African origin. She comes from a privileged background and yet class does not protect from discrimination, although, as she recognizes, class provides some entitlement if, and only if, one assimilates. Then the group remains “entre-soi”, “among friends”, a sort of homogeneity defined by class, race and gender. Otherwise the response is merciless. Paradoxically, privileged class is often the source of the most disguised but nasty racism, according to Boni-Claverie.

She demonstrates that the personal is political. Her grand parents lived together for 50 years, her grandmother passed first and her grandfather soon after. Boni-Claverie concludes that together they made themselves believe that the advent of a post racial society had happened. She ends by asking: How much time for that to be a reality for all?

Liberation opened a page for testimonies: “You know you are Black when…” The page filled quickly with important, must-read testimonies. The documentary will be distributed to associations to raise awareness; it came with a petition to promote the establishment of quantitative data on discrimination. It is the responsibility of the French State to have its principles written in its Constitution respected.

(Photo Credit: RFI)