Nzinga King

In July 2021, 19-year-old Nzinga King was taken into custody in rural Jamaica, pepper sprayed, and then, while in custody, was forcibly subjected to having her hair cut. After some public outcry, an internal investigation was launched … sort of. The results came out this past week. According to the Director of Public Prosecution, it was all fine. In August 2018, 50-plus-year-old Yvonne Farrell was in her partner’s car in Stevenage, about a half hour north of London, when the car broke down. When the police arrived, with the tow truck, Yvonne Farrell refused to give her name. She saw no reason to. The police took her in. Since she didn’t give her name, they stripped her naked and left her on the cell floor for three hours. Yvonne Farrell sued, and last. Week, the police apologized and paid £45,000 in damages: “I accept that you should not have been arrested. I am extremely sorry for any injuries that you suffered as a result of the actions of Hertfordshire Police. On this occasion we got it wrong. I apologise unreservedly.” Nzinga King and Yvonne Farrell are Rastafarian women … unreservedly.

Nzinga King was travelling with friends in a taxi. Some were not wearing masks. Nzinga King was wearing a mask. The police stopped the car to question those not wearing masks. The police pepper sprayed some in the car. Nzinga King got out and started arguing with the police. She was arrested for disorderly conduct. On July 22, she received a $40 fine or 10 days in jail. She couldn’t pay the fine, and so went to jail, where a police officer cut her hair. As Jamaican journalist Emma Lewis noted this week, Nzinga King “had several counts against her from the start”: She is young. She is Black. She is poor. She is Rastafari. She is a woman. She is a rural dweller. With all that, Nzinga King should consider herself lucky to have been `merely’ humiliated. Right?

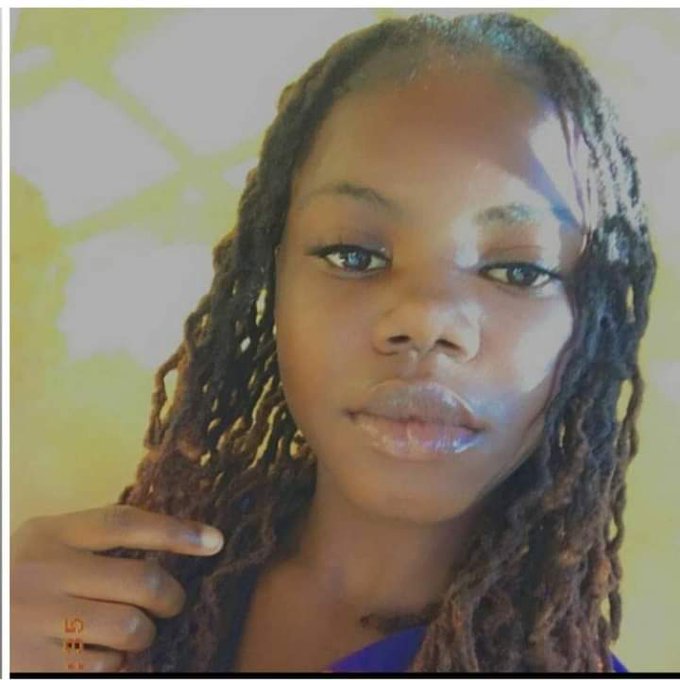

Yvonne Farrell is not young, poor or a rural dweller. She is Black. She is Rastafari. She is a woman. And she knows that and she knew that, and she knew that to be criminalized for the nexus of Black, Rastafari, woman is unjust. As Yvonne Farrell explains, “I could have been a Jewish woman. I could have been a Muslim woman … That just shows they wanted to humiliate me – they did humiliate me.” Yvonne Farrell has since `relocated’ to somewhere in the Caribbean.

Two years ago, in 2020, in London, Ruby Williams won an out-of-court settlement of £8,500 for the abuse she suffered, for wearing her hair in an Afro, for Being Black, from the age of 11 years old on. Two years ago, in 2020, Jamaica’s high court ruled that a school was within its rights to tell a 5-year-old girl student, identified as Z, that she must cut her dreadlocks or leave school. By all accounts, she was an excellent student. By all accounts, she had not in any way prevented others around her from pursuing their education. To the contrary, she was described as an ideal student and learner who helped her fellow students. But Z’s desire to learn was deemed Constitutionally inferior to the politics of Black girls’ hair. Two years later, Yvonne Farrell and Nzinga King lock arms with Z and Ruby Williams. Compensation is not enough, apologies won’t do. Meanwhile, the State-sponsored war on Black women bodies continues.

Yvonne Farrell

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit 1: Petchary’s Blog) (Photo Credit 2: BBC)