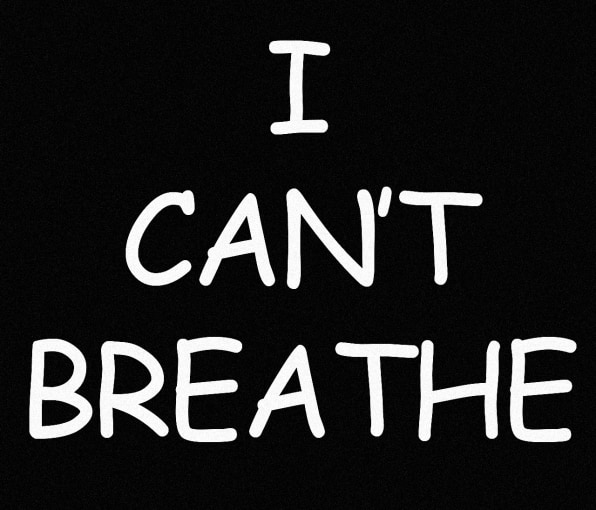

E.Y., age 11

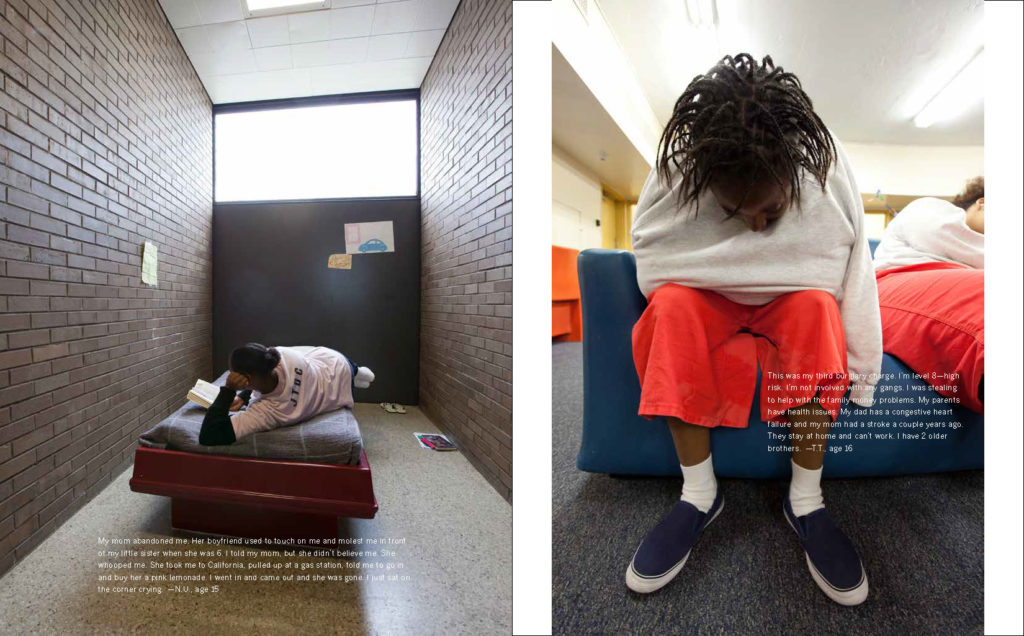

The Texas Tribune reports this month, and once again, that Texas’s juvenile detention system is still in crisis, again. As Tribune criminal justice reporter Jolie McCullough noted in an interview yesterday, “The Texas Juvenile Justice Department has really always been – it’s always been in crisis. It’s been more than a decade of crisis after crisis. There’s sexual abuse scandals, mistreatment allegations. They’re actually under federal investigation right now from the U.S. Department of Justice.” The Texas Juvenile Justice Department has always been in crisis. While the system has reduced from thousands to hundreds, that step is of little benefit to those still caught inside. Children are spending 23 hours a day, days on end, alone in their concrete cells, equipped with a mounted shelf and a thin mattress: “The lucky ones have a small window to the outside.” Children are `self-harming’ in record numbers. The “system is nearing total collapse.” Nobody in that system is lucky. And where are the girls and young women? They are in the Ron Jackson State Juvenile Correctional Complex in Brownwood … for now.

In 2008, the ACLU filed a class action lawsuit against Texas challenging inhumane conditions at the Brownwood State School, which was later renamed Ron Jackson. The conditions included invasive, frequent strip searches; frequent, extended use of solitary confinement; frequent application of “brutal physical force.” Why were girls and young women in Brownwood, in the first place? Minor offenses, minor misbehavior, but really for being girls and young women who had survived violence and were living with trauma, depression, and mental health issues. Any of those would send a girl or young woman into solitary, often and for long periods of time. Who in that system, in the early 2000’s, was lucky? That class action lawsuit covered “all girls and young women who are now or in the future will be confined in the Brownwood State School”. From 2008, is 2022 “in the future”, because the conditions at Brownwood, now known as Ron Jackson, are still brutal.

In 2012, the Texas Coalition Criminal Justice Coalition reported on girls’ experiences in the Texas juvenile justice system. They found: “Girls in the Texas juvenile justice system do not receive sufficient help to deal with past trauma in their lives … Negative interactions with staff are the least helpful part of the juvenile justice system; they are also the number one thing girls want changed in the juvenile justice system … Girls in the Ron Jackson state secure facility are extremely isolated from their families.” Anna Yáñez-Correa, Executive Director of the Coalition, noted, “We are failing many of these traumatized children. Half of the girls we surveyed at the Ron Jackson State Juvenile Correctional Complex told us that their time in county juvenile facilities either did not help or actually did more harm than good for dealing with their past trauma. Tragically, eight percent told us that their time at Ron Jackson is doing more harm than good, suggesting that our juvenile justice system may be re-traumatizing many of these domestic violence survivors.” As one girl explained, “Counselors, staff, the legal system – they can’t understand where we’re coming from and what we need. They’re always trying to judge us for our trauma.” Ten years later, the trauma and the judging continue and deepen.

In 2019, the U.S. Justice Department’s Sexual Victimization Reported by Youth in Juvenile Facilities, 2018 found that, nationally, 7% of youth in juvenile facilities reported having experienced sexual victimization, which was down from 9.5% in the previous report, in 2012. Texas was an outlier, reporting 10.3%. Ron Jackson’s lucky residents reported 14%, as they had in 2012. In August 2019, a guard at Ron Jackson was fired and jailed for sexually abusing a “resident”. For those incarcerated girls and young women, when does “the future” begin?

Last year, the U.S. Department of Justice launched an investigation into the abuse of children and teens in Texas juvenile detention centers. At the press conference announcing the investigation, Chad Meacham, acting U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Texas, said, “We are particularly troubled by the news coming out of the facility in our district, especially reports of misconduct by staff.” That was an explicit reference to the particularly troubling Ron Jackson State Juvenile Correctional Complex.

Last year, the Texas Juvenile Justice Department reviewed its own “progress”. Under the heading “Achieving Balance Between Supervision and Population”, the report addressed the particularities of girls at Ron Jackson: “Girls have very high levels of trauma, with 86 percent having 4 or more Adverse Childhood Experiences, and when we screen them for potential sexual exploitation, 36 percent are of clear concern and 55 percent are of possible concern. The small number of girls in state care quite often have an intense level of trauma that causes them to respond automatically and aggressively to stressors. Girls need an overall ratio of 1 direct-care staff member to 6 girls; for the most violent youth and those with significant mental health needs, that ratio is 1 to 4. Of girls in secure facilities 63 percent have been placed on suicide alert at least once— about twice the percentage of TJJD secure youth overall. When this occurs, they often need a 1 to 1 ratio … 84 percent of girls have four or more Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) as compared to 12.6 percent of the public, 91 percent of girls are clear or possible concern for child sex trafficking … This is the highest concentration of acute needs and risk in the history of the agency.” How does the State respond to the highest concentration of acute needs and history? Diverting federal coronavirus relief funds to Texas’ “border security mission.”

In June 2022, Shandra Carter, Texas Department of Juvenile Justice Interim Director, wrote to her staff to outline her response to the department’s situation. The letter begins, “I am incredibly disappointed to have to inform y’all that we will temporarily be halting intake of youth committed to TJJD.” She then outlines five steps, including moving the female behavioral stabilization unit from Ron Jackson unit to the McLennan County State Juvenile Correctional Facility and “reducing’ the female population by 16 at the Ron Jackson State Juvenile Correctional Complex by moving them to the McLennan County State Juvenile Correctional Facility, currently holding 242 males. So, the reduction involves no reduction but rather moving 16 girls and young women to an all-male facility that is also under federal investigation.

The Texas Juvenile Justice Department has always been in crisis. From the first report to the latest, the “crisis” is always attributed to “staffing shortages”. While staffing shortages exist, the crisis in the Texas Juvenile Justice Department is prison. Texas responds to violence against girls and young women as a matter of criminal justice in which girls and young women are condemned for their trauma as well as their survival. Moving girls and young women from one prison to another does not reduce their population, it reduces their dignity and stature and intensifies their trauma. Blaming the situation on staff shortage refuses to acknowledge the truth, one which Mark Patterson, head administrator of the currently empty Hawaii Youth Correctional Facility, explained, “We no longer want to keep sending our kids to prison … Do we really have to put a child in prison because she ran away? What kind of other environment is more conducive for her to heal and be successful in the community?” Stop offering alibis, such as staff shortages, for our own vicious policies; stop sending children to prison; stop treating trauma and mental illness as a crime. Work towards healing in the community and beyond. Begin, again, by stop sending children to prison. Where are the girls and young women; when does their future begin?

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: Richard Ross / PBS)