On December 17, 2011, the Alexandria City Council overwhelmingly voted to ignore low- to moderate-income residents of the Arlandria neighborhood who came to City Council to oppose a so-called redevelopment plan. Most of the residents who came and spoke were Latinas. Some were high school or college students. Some were young women workers. Some were women elders, who have lived in the neighborhood for decades. Many were members of the Tenants and Workers United, others small business owners, and some simply neighbors and friends.

Women who had grown up in the neighborhood, joined youth groups and women’s leadership groups and now attend college. Women from outside women’s leadership groups who had moved to the neighborhood because of its diversity and promise. To a person, they described their fears and aspirations, and a planning process that actively excluded them. To a person, they were ignored.

Each woman looked the Council members in the eyes and asked, or pleaded, or demanded that they slow down the process, that they listen, really listen, to what was being said. Each woman explained that she has had a critical role in building and sustaining the vibrant community of Arlandria. Each woman was ignored.

The women argued that the plans for upscale development [a] are a lousy deal, [b] threaten the fabric of the community, and [c] were devised without any real consultation.

Here’s the plan: turn a low-lying strip mall into two massive six-story buildings that will include 478 residential units. If the buildings are too high, as they are by city standards, throw in 28 `affordable’ housing units … out of 478, and get a waiver. This `affordable’ is designed for those earning around $50,000 a year. Basically, no one currently living in Arlandria earns that. So, no one currently living in Arlandria will qualify.

Then, claim that 450 upscale units in a tight neighborhood will have no impact on the rest of the housing market in the neighborhood. Nearby landlords will not raise their rents. No one will be dislocated. There is no need to worry about gentrification.

When the actual neighbors look at you in disbelief, tell them that they’re getting 28 new units that weren’t there before. Those units will go to someone else, but that’s not `our’ problem.

If anything else comes up, such as questions of traffic and parking, questions of public lands and recreational centers, respond with assurances and vague promises that everything will turn out fine when the time comes.

That was the plan and that was the argument presented to the residents of Arlandria by the Alexandria City Council and its staff.

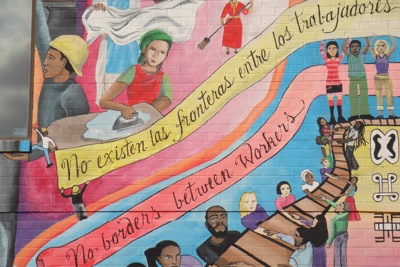

The Council altogether ignored the fabric of the community. For almost thirty years, the Arlandria community has struggled to create a decent place for working people across generations; for Central and South American, African and Asian immigrants and their children, many of them US citizens; a decent place for all low income people; a decent place for all people. The Council refused to recognize that labor of dignity. Sometimes, decades of creating a community fabric must be tossed onto the trash heap of history… in exchange for 28 `affordable’ units.

The City Council did respond, at length, to the claims of lack of inclusion. They insisted that they had tried to `include’ the residents, but the residents had proven themselves to be difficult. The City Council, with one exception, Alicia Hughes, then began to express resentment at the exclusion claims and its claimants.

What’s going on here? The City Council outsourced inclusion, and democracy, to its staff. The staff reported that they were doing the very best job possible. Who monitors the staff? The staff monitors itself. When over forty people came to the City Council to say that the staff had not included them and never had a real consultative process, and that the so-called advisory groups were mostly developers and landlords, what did the City Council do? It turned to the staff, and the staff said, “We tried.”

And nobody on the City Council asked, “Why then do all these people say you have created a culture of exclusion?”

What happened in Alexandria happens everywhere. The State outsources inclusion, under the mask of liberal democracy, and then, when those who have been excluded protest, the State resents their presence, their voices, and their claims.

Meanwhile, in Arlandria, as everywhere, the women are organizing. And, as one Latina college student said, they vote.

(Photo Credit: WAMU.org/Emily Friedman)